Zikhona Valela’s campaign against erasure

The historian’s debut book documents Black Consciousness leader Mapetla Mohapi’s remarkable life and death in detention, and his widow Nohle Mohapi-Mbetshu’s fight for justice.

Author:

31 May 2022

On 15 April 1996, Nohle Mohapi-Mbetshu opened the Truth and Reconciliation Committee (TRC) hearings, as the first person to give testimony. The transcript of her words, translated from isiXhosa, is harrowing. This is not because of her account of how her husband, Mapetla Mohapi, was harassed and detained throughout their time together, or how his death on 5 August 1976 was presented as a suicide, despite clear evidence to the contrary, or even because of her own subsequent imprisonment and intimidation by the apartheid state.

What is most haunting is the vivid flashes of their life together, which permeate her account. She describes how Mohapi insisted that she stick with him when he left home because police regularly attacked their house. And she talks about how on Sunday drives scouting around for beautiful houses in King William’s Town, dreaming of a world beyond space segregated by race, Mohapi would assure Mohapi-Mbetshu: “We are going to own that house one day.”

Related article:

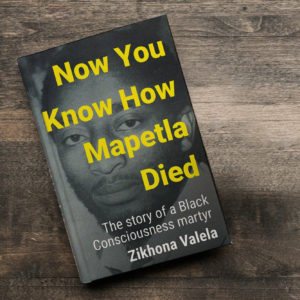

The Mohapis would also stroll through the botanical gardens, a stone’s throw from where historian Zikhona Valela grew up in the democratic dispensation Mohapi knew was coming. In the preface to her debut book, Now You Know How Mapetla Died: The Story of a Black Consciousness Martyr (Tafelberg, 2022), Valela explains being motivated by “a curiosity to see if this ‘lost’ history could be retold after so much time has lapsed, but also from the need to tell the stories of locations that don’t enjoy the same attention as the urban centres like Johannesburg”.

Her book is an attempt to bring Mapetla Mohapi to life by shining a much-needed light on both a man who was more than his death and a woman who is more than her grief.

Mapetla Frank Mohapi

The first half of the book sketches out Mohapi’s life, with a disclaimer that “it is difficult to write about him 45 years after his death”. His parents and most of his siblings and friends have died. The events in which he was involved took place decades ago.

Already participating in protests during high school, Mohapi’s political activity intensified when he studied social work in 1970 at the University of the North at Turfloop, one of the strongholds of the Black Consciousness Movement, represented at the time by the South African Students Organisation.

The Black Consciousness Movement emerged five years after the Rivonia Trial concluded, ending with the incarceration of most of the ANC leadership active at the time. Mohapi recruited students to the South African Students Organisation from Turfloop and throughout the Eastern Cape, travelling frequently to the University of Fort Hare and the Federal Theological Seminary.

After detailing the intricacies of student politics at university, Valela offers an absorbing account of both the national and regional implications of Mohapi’s work, describing the impact of nationwide celebrations in solidarity with Mozambique’s Frelimo party, organised by the Black Consciousness Movement.

She also presents a bittersweet portrayal of Mohapi and Mohapi-Mbetshu’s meeting and marriage in 1973, and the birth of their two daughters, Motheba and Konehali.

Related article:

Valela shines in her efforts to humanise Mohapi through his love for music, rendering him vividly through the sounds of Roberta Flack, his favourite singer. She muses that Flack’s ability “to ebb between the political and the romantic with ease is likely what appealed to Mapetla” and demonstrates the same ability when dexterously weaving together the sketchy details of Mohapi’s death in detention with the fragments available about his life.

She writes, “This book feels more like a tale of death than it is of life … because death lives side by side with his short but remarkable life, the task of retelling this story involves a biography of apartheid’s lies.”

The title of this book, Now You Know How Mapetla Died, serves two functions. It draws from a confession made to Thenjiwe Mtintso while Captain Richard Hansen strangled her with a cloth in the same interrogation room Mohapi allegedly died in on 5 August 1976. Mtintso joined the liberation struggle through the South African Students’ Organisation while studying at Fort Hare and was a colleague of Mohapi. She recounted her own experience in detention, including Hansen’s confession, during the inquest into Mapetla’s death that began in King William’s Town on 17 January 1977. The title also allows us to place Mohapi in the history of a system that was designed to eliminate dissenting voices. It matters then to broaden the personal story to the wider contexts that shape the activist, the Black man Mohapi had to be, and the widow Mohapi-Mbetshu ended up becoming.

Mohapi’s death is one of the most significant in detention. He was the first Black Consciousness Movement leader to die, sparking a wave of crackdowns on activists and resulting in the banning of the South African Students Organisation and the Black People’s Convention after the death of Steve Biko in 1977.

Valela not only links Biko’s death with that of Mohapi, but also does justice to their close friendship and to Mohapi-Mbetshu’s work as Biko’s secretary. She explains why much of what we understand of the Black Consciousness Movement comes through Biko’s writings, and expands on his ideas by grappling with what this legacy means in and for South Africa today.

Nohle Mohapi-Mbetshu

Valela helps readers see Mohapi as a person, but she really excels at capturing Mohapi-Mbetshu’s tireless efforts to uncover the truth about his death. Although Valela’s cataloguing of facts is forensic – from the pathology report detailing his wounds to the investigations into the validity of his supposed suicide note – the real skill is the care with which she writes about Mohapi-Mbetshu.

Before 2018, when Valela began her research, “there was no serious look into Mohapi-Mbetshu’s quest for justice for her husband”. During an interview over Zoom, Valela explains that her interest in the erasure of woman in the liberation struggle stemmed in part from her master’s thesis on Winnie Madikizela-Mandela as the intellectual face of the anti-apartheid popular struggle. There are surface-level parallels between the two women: mothers to two daughters and wives to activists who sacrificed much for the cause, albeit with different levels of visibility.

Related article:

Valela digs deep, and her efforts to counter Mohapi-Mbetshu’s erasure are testament to her own perseverance. Valela says it was tricky to get to Mohapi-Mbetshu’s memories without traumatising her, given that the latter’s search for the truth took place during a period in which she was tortured. But stylistic choices such as including photographs of Mohapi-Mbetshu, her children and family friends are a welcome accompaniment to those of Mohapi, and a necessary reminder of the absence with which they were forced to live.

Still no answers

At the start of the book, Valela emphasises its importance: “This work matters and exists at an interesting point in our history. The euphoria of 1994 has waned, and South Africans are beginning to reflect more seriously.” At the end, she grapples with difficult questions around forgiveness and redress in the context of reopened inquests into the deaths of activists, which have recently made headlines.

The reality, however, is that “at present, we remain with the narrative that no one is to be held responsible for Mapetla’s death”. The SABC website of the TRC recordings continues to describe Mohapi as having “allegedly hanged himself in King William’s Town … in 1976”. The transcript of Mohapi-Mbetshu’s testimony is riddled with poor translation – her maiden name, Haya, is misspelt and rendered in lower case as “higher”.

Related article:

But Valela’s work offers great glimmers of hope for what activism in the archives can do. She found the pathology report at Wits University Historical Papers – the family did not know it existed. Her approach to historiography is careful without being circumspect, and this book is characterised by a conscious effort to shield the Mohapi family from further trauma while working to uncover their story.