Yes, we Can!

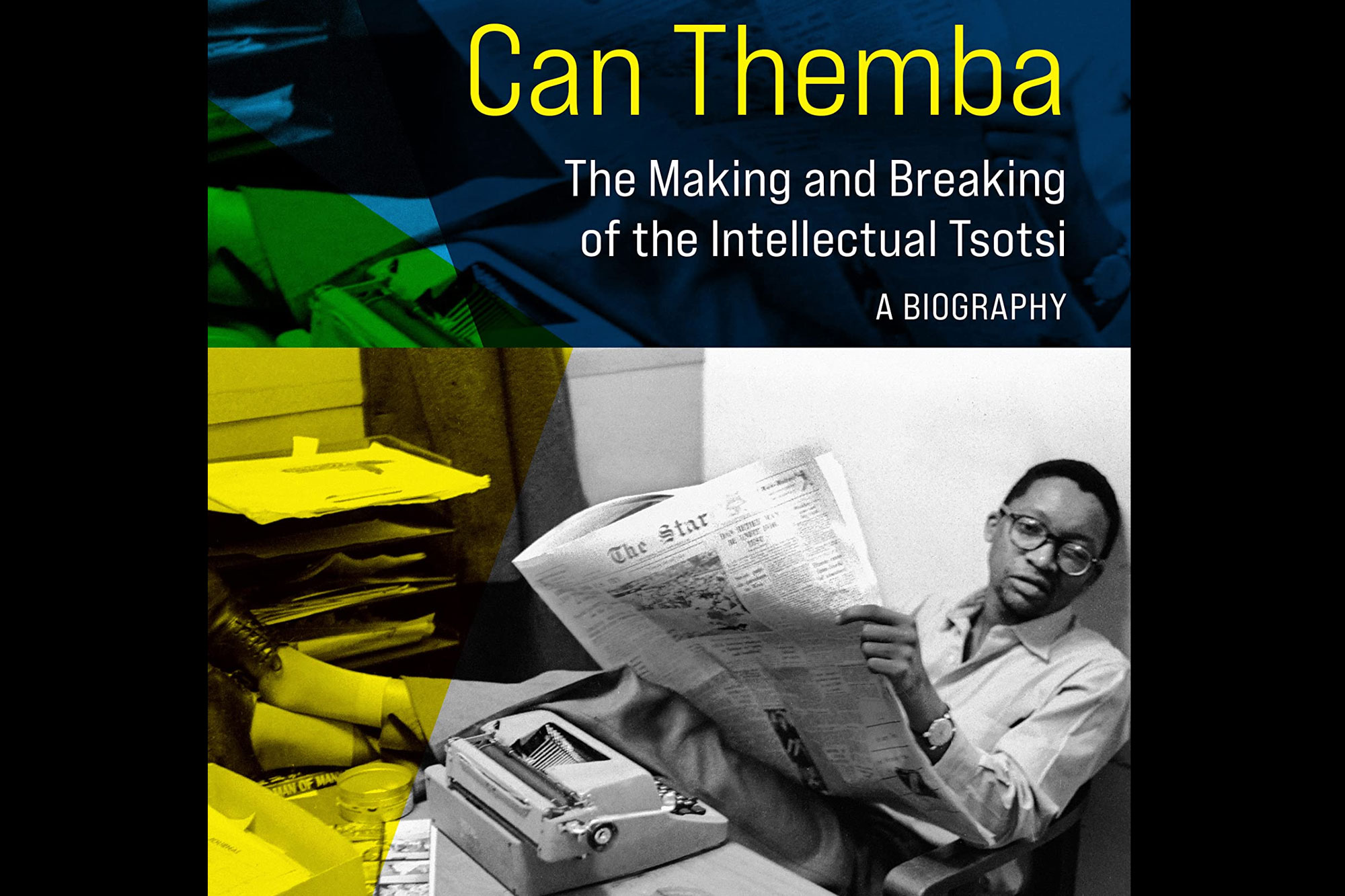

Siphiwo Mahala’s biography of Can Themba, the Drum-generation journalist and short-story writer, is a kind of resurrection, underlining how his work is both vital and enduring.

Author:

17 May 2022

Although Siphiwo Mahala’s Can Themba – The Making and Breaking of the Intellectual Tsotsi (Wits University Press, 2022) principally seeks to draw attention to the timeless metaphysics of the writer’s stubborn texts, the early chapters of the book are replete with much sadness and brokenness.

Mahala’s project is a continuation of the symbolic memorialisation that began in earnest at Themba’s funeral at St Joseph’s Cathedral in eSwatini in September 1967. Here, he writes, “a man who professed to be an atheist, an existentialist, and who was dubbed a romantic nihilist – Can Themba, the boisterous, beloved boozer – was buried like a bishop, becoming the first ‘civilian’ to be interred in the St Joseph’s cemetery”. Mahala’s intellectual commitment is also ritualistic – a quest to put together the dispersed fragments of Themba’s life, “a reassembling of a dis-membered tale into a composite whole”.

As Mahala observes: “While the autopsy on Themba’s body revealed that he had died of coronary thrombosis, regardless of the official cause of death, the lifeless body that was carried out of that room in Manzini had begun dying many years before. The 8th of September 1967 marked the culmination of a downward spiral in a destructive journey that had begun when he joined Drum in 1953 – perhaps even before then.”

Related article:

He is right. Themba’s world was marked by increasing state violence against Black people and the silencing of human rights protests of many forms. Writers such as Themba were not welcome in organised circles of white writing – what the local chapter of PEN absurdly called, “the whole English community of southern Africa”. No wonder in its 1960 edition, the year of the Sharpeville massacre, PEN celebrated the 50th anniversary of the union of South Africa, showing Black writers and the country’s oppressed people a dirty and ugly white middle finger. In 1966, 46 exiled South African writers, including Themba, were banned under the Suppression of Communism Act of 1965.

Themba died a banned writer. “Banning meant that he could not be published nor quoted in South Africa, which probably discouraged him from writing, as the chances of being published were greatly diminished,” Mahala writes. Yet, by picking at the famed Drum writer’s dry bones, so to speak, Mahala is not just taking us back to the world of Can Themba, but essentially he resurrects the man. In part, this is because, as Jacque Lynn Foltyn puts it, “we have imbued the dead body with the tension of paradox, making it extraordinary and banal, wild and tame, useful and useless”.

Journing into Themba’s worlds

Mahala successfully makes Themba’s body of work useful, life-giving and enduring. He writes against what Fazil Moradi, in the mould of the Portuguese global cognitive justice scholar Boaventura de Sousa Santos, calls, “the murder of knowledge”. Also, as the book progresses, it becomes obvious that, like a forensic pathologist, the author is arguing vehemently that not even the harsh winds of time have succeeded in fully dismembering Themba’s mortal remains because through his work, he has no way to die.

“I see him as a living ancestor,” says literary historian, publisher and former journalist Mothobi Mutloatse. He is right. Themba’s life and writing are exemplary texts in relentless self-reflective efforts towards the sublime as a lived (albeit, tragic) human experience.

From the first chapter, Mahala invokes memory as the ominous knocking-on-the-door of a mysterious and utterly heartbreaking death in distant lands, where not even a dog or a cat stands vigil to mourn the sudden passing of a beloved companion.

Related article:

“With one eye closed, he peeped through the keyhole. He could make out a lanky man lying in bed with his feet pointing heavenwards. It was definitely the man he was looking for. Why on earth was he not opening? He banged on the door with his fist, shouting his name: ‘Bra Can! Bra Can Themba!’ No response. He hammered on the door. Silence. It was Friday, 8 September 1967. The 25-year-old Pitika Ntuli had travelled all the way from Lubombo, a journey of about 25km, to Manzini in Swaziland (now the Kingdom of eSwatini), where his mentor rented a flat.”

The dramatic opening chapter has a matter-of-fact tone. It is paradigmatic of the reality of Themba’s sudden demise at 43 and that of some of his iconic peers at Drum in the 1950s, Nat Ndazana Nakasa, 28, in New York on 14 July 1965, and Todd Tozama Matshikiza, 47, in Zambia on 3 March 1968. Mahala writes: “Whatever happened, whatever the circumstances, the objective reality is that Themba died an outsider: away from his ancestral land, away from the House of Truth, and away from his family.”

Although Mahala’s narrative arc is not strictly chronological, there is a conscious effort towards this, not in the pattern that is common with historians, but in a dynamic, zig-zag style that often makes imaginative writing more evocative and memorable. He, for instance, introduces the reader to Themba, born on 21 June 1924 in Marabastad, the setting of fellow Drum colleague Es’kia Mphahlele’s childhood memoir, Down Second Avenue (1959). Mahala’s book orbits Themba’s many worlds. This includes Marabastad, Soweto, Sophiatown and Fort Hare, where he immersed himself in William Shakespeare, wrote poems and met diverse figures such as Robert Sobukwe, Dennis Brutus, and Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

Meticulous research

Based on his doctoral thesis Inside the House of Truth: The Construction, Destruction and Construction of Can Themba, completed at the University of South Africa in 2017 and supervised by Michael Kgomotso Masemola, Mahala’s book revisits Themba’s life “more than 50 years after his passing” to help keep Themba’s name and writing alive in the public imagination. Shocked that no one had yet written a full-length biography, Mahala committed himself to addressing this void in South African humanities, admitting that “re-membering is premised on the view that vital elements of a story can be dis-membered”.

Through meticulous research and powerful rhetorical gestures such as deliberate repetitions, Mahala writes with warmth and a generosity rooted in history as collective memory – bold Black acts where the dead rise still scarred but never afraid to laugh at the absurdities of whiteness and its laboratories of capitalist violence.

One cannot analyse the explosive decade of Themba’s making and breaking without underlining the edifice of apartheid and its attendant taxonomies of treating all Black people as sub-human. Mahala’s book reads like an extended and timeless obituary, whose deep dives, and tentative and definitive hues reflects the author’s easy and rewarding access to Themba’s family members, including, among others, his wife, Anne; daughters, Morongwa and Yvonne; Drum colleagues such as Harry Mashabela, Lewis Nkosi and Juby Mayet; and former students and mentees Sol Rachilo, Muxe Nkondo and Mbulelo Mzamane.

Related article:

In the latter years of his life, Nkosi used to regale me, journalist Tiisetso Makube and others with stories of Themba’s towering presence in the newsroom. In the book, former journalists Joe Thloloe and Mayet confirm this – Themba’s abiding presence as teacher in the newsroom. But although Mahala does not interrogate this point in any way, it is clear that the beloved teacher was also a misogynist. In a conversation with Lindiwe Mabuza, then an exiled South African teacher at Manzini Central School in Swaziland, a talk encouraging the young teacher to consider writing a craft degenerates into toxic masculine vulgarity. This is what the great Themba is quoted to have told Mabuza: “When you start writing the first thing you must say is, ‘I do not only menstruate, I think because I’ve got a brain.’” This needs attentive critique, to probe the gender prejudices of his subject.

Despite this shortcoming, Mahala’s Can Themba – The Making and Breaking of the Intellectual Tsotsi is a work of excellence in a long journey of putting the decaying cadaver of Black lives and memories under the sharp knives of decolonial scholarship. Mahala’s book is a welcome addition to an insightful new body of Black South African biographical writing by a new generation of exciting and committed Black scholars. This includes Hlonipha Mokoena (Magema Fuze), Nomsa Mwamuka (Miriam Makeba) Bongani Ngqulunga (Pixley Seme), Pumla Dineo Gqola (Miriam Tlali) and Bongani Nyoka (Archie Mafeje) to mention a few. Undoubtedly, these biographers are now answering Herbert Isaac Earnest Dhlomo’s 1947 call, and going beyond it – writing books on Africa that centre those who define our culture.