Women bear Covid-19’s silent burden

The pandemic has disproportionately affected women, who have suffered more job losses and greater emotional distress. Yet few can access the mental health help they need.

Author:

12 November 2021

More than a year after the Covid-19 pandemic hit South Africa in March 2020, Evelina Masombuka, 45, and Thandi Mehlo*, 55, are still trying to recover from its effects and devastation.

For two years, Masombuka, from Hendrina, Mpumalanga, worked as a cook at a crèche in Middelburg, while for 16 years, Mehlo, from Delft in Cape Town, worked as a domestic worker for a family once a week. This was before the pandemic led to them losing their jobs and they became two of many women who have been disproportionately affected by the outbreak.

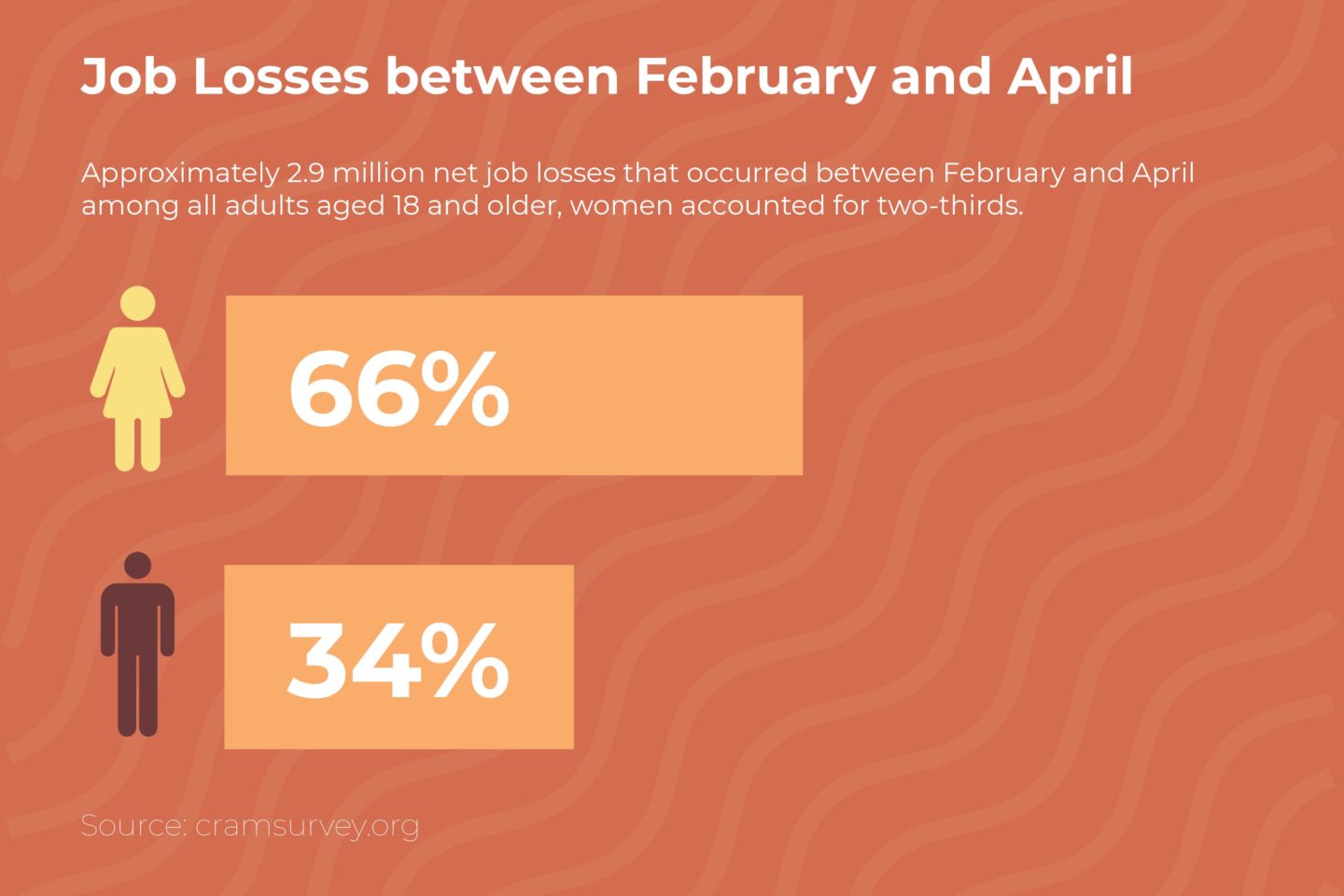

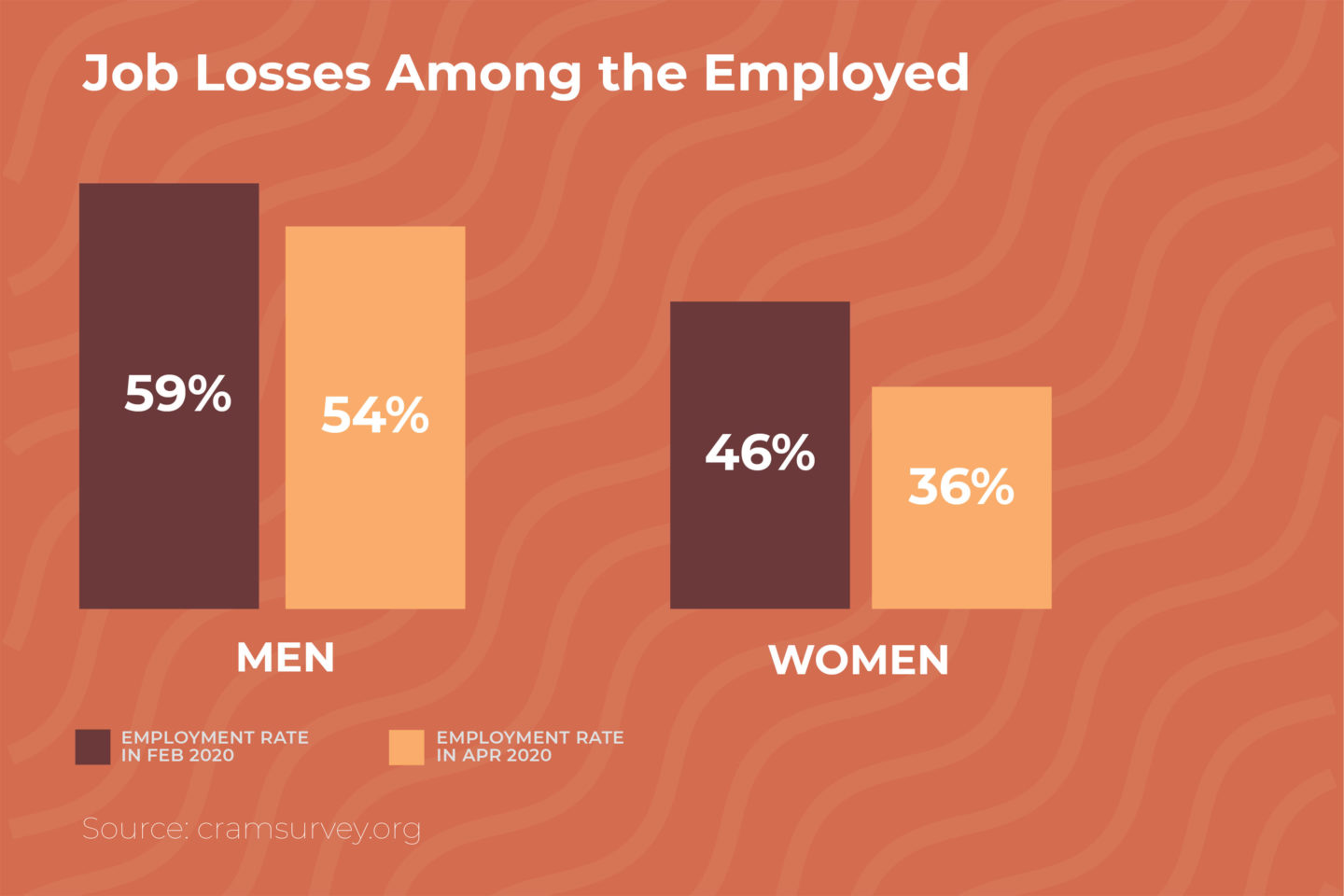

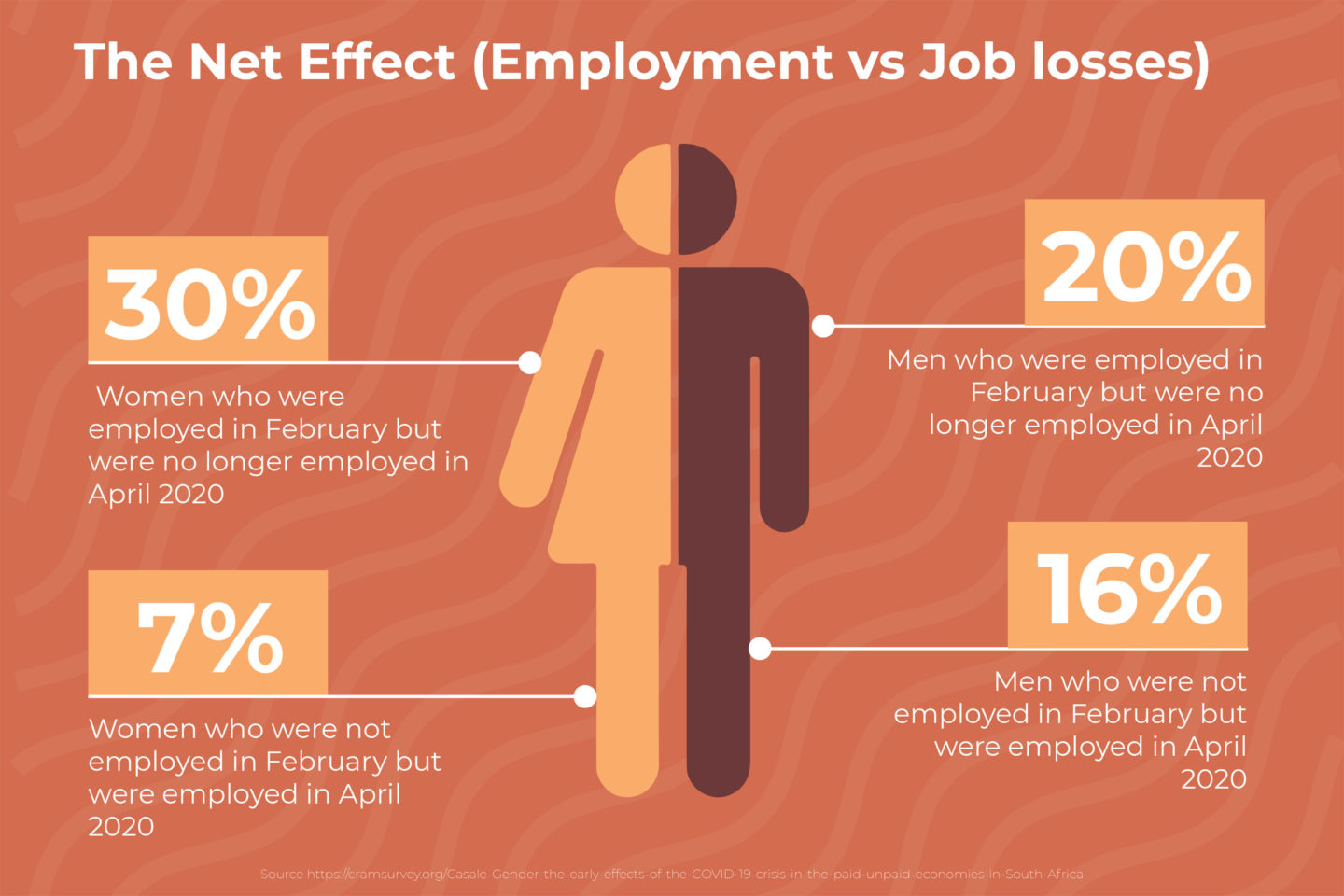

A 2020 report by the National Income Dynamics Study – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (Nids-Cram) revealed the gendered effects of the pandemic. “Of the approximately 2.9 million net job losses that occurred between February and April [2020] among all adults aged 18 and older, women accounted for two-thirds. Because women were more likely than men to have lost a job and less likely than men to have gained a job, overall, women accounted for the bulk of net job losses,” the report stated.

Out of work

Masombuka was forced out of her job over a wage dispute in November 2020. Initially, she was earning R4 800 a month. When the Covid-19 lockdown came into effect and contact learning was suspended, Masombuka was asked to stay at home. She received her full salary until July 2020, when classes resumed.

Then her employer reduced her salary to R2 400, which barely covered her monthly transport cost of R1 200 for the 100km round trip to her workplace from Hendrina. She lives with her two sons, aged 15 and 28. Her eldest does not work and she battled to meet her family’s needs. But her employer gave her an ultimatum: accept the reduced salary or resign. Masombuka says her employer refused to register her for the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) Covid-19 Temporary Employer-Employee Relief Scheme, which is financial assistance given to employers to continue paying salaries to employees affected by the pandemic.

After a few months, the crèche owner relented and offered to increase Masombuka’s salary to R3 360, which was still way below what she needed to meet her transport costs and household needs. Masombuka filed a complaint with the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration, hoping to have the matter resolved quickly.

Frustrated by the delay and the little money she was earning, Masombuka stopped going to work in October. The same month, the arbitration decision was made giving her two options: return to work and continue earning the reduced salary, or return home and wait for her employer to decide whether to retain her services at the old salary. In November, Masombuka’s employer sent her a three-page letter of dismissal via WhatsApp.

Related article:

Masombuka attended three case hearings and was awarded a settlement of one month’s salary, which she accepted even though she was not happy. “I was tired of the ups and downs, and the money for travel to attend the arbitration hearings was also a problem,” she says.

Her anxiety and stress manifested in a “stiff neck, headaches, struggling to wake up in the morning, difficulty thinking”. Masombuka was diagnosed with depression and put on medication, which has not worked. She has consulted a doctor four times with no change to her condition, which worsened after her former employer refused to remove her name from the crèche payroll, making it impossible for Masombuka to apply for the R350 Covid-19 social relief of distress grant.

When the country went into lockdown in March last year, Mehlo was among those who stopped working. The family continued to pay her the R250 she received for a day’s work, but a month later that amount was cut to R200, meaning her salary dropped from R1 000 to R800 a month. She eventually lost her job in late March 2021 because her employer was worried the family would be infected with Covid-19 as she travelled to work using public transport. Mehlo says her employer did not register her with the UIF. An employer is supposed to register any employee, including domestic workers, who work for more than 24 hours a month with the fund. The monthly contribution to the UIF is 2% of the worker’s gross salary a month. The employer is supposed to contribute 1% to the fund while the other 1% is deducted from the employee’s salary.

She was sent home in April with a severance pay of R2 400, which was paid in tranches of R800 for the next three months. This is less than the R3 200 to which she was entitled, says Pinky Mashiane, founding member of the United Domestic Workers of South Africa network. Mehlo, who has eight children – three of her own and five orphans she has taken under her care – is in obvious pain as she talks about her job loss and the problems she faces trying to care for her family. “I lock myself in my room to stop lashing out at the children,” she says.

She has since been able to find help from a community-based counsellor who has recommended she seek professional help. Mehlo says she cannot afford the fee or even the transport to attend professional counselling services.

Providing support

Vanessa Reynolds is a programmes coordinator at The Women Circle (TWC), a network that has provided access to education and safe spaces for marginalised women since 2006. She says Covid-19 has greatly affected women.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on women’s mental health as it has exacerbated the already harsh conditions under which unemployed or semi-employed people manage to care for their families. Food security is precarious. Job losses within the household [and] inability to pay rent lead to fear of eviction. This and the loss of key family members or the fear of losing family members add to the uncertainty,” Reynolds says.

Before her dismissal, Masombuka was doing a study course on early childhood development for which she paid with borrowed money. “Because of Covid-19, I am unable to continue with my studies. I lost my job. I don’t have money,” Masombuka says.

Her bed got repossessed as she failed to make payments. To survive, she started selling scones in November last year. “I saw it will take a long time to get another job during Covid-19. It’s better to bake and sell as it gives me money for food at least,” Masombuka says.

Related article:

Mehlo says she has contemplated suicide many times. “I once took all my pills as I thought it was better to die than continue struggling to pay for basics such as food, water, electricity and even the rent. I am glad I did not die as l now realise my children will suffer more if l am gone,” she says.

Apart from the job loss, the other cause of her anxiety is the cost of registration for her daughter’s nursing degree – R2 500. She also realised she would not be able to pay for her son’s ulwaluko, a rite of passage during which boys are initiated into manhood. The ritual, excluding the celebratory feast umgidi, which usually accompanies the final “coming out” phase of circumcision, costs about R15 000.

A place of hope

Magdalena Mtshiza, 63, from Delft, joined TWC because she needed someone to talk to and could not afford a professional counsellor or therapist. “We come together as women and share our experiences,” Mtshiza says.

TWC has 10 chapters in communities across the Cape Flats. “It starts with a cup of tea, followed by small talk if a particular topic has raised a description of how they feel, what has happened at home, the uncertainty of where they will access food. Some will break down. TWC’s [informal] workshop approach provides an opportunity for women to discuss openly, and many things are disclosed that would otherwise be kept secret. Some do not disclose,” Reynolds says.

The workshops are hosted weekly at people’s homes, community centres or any other free available spaces in the community. They are supported through issue-based partnerships with non-governmental organisations to provide information in focus areas, according to Reynolds.

Joyce Malebo, 63, from Gugulethu, and Mtshiza say they joined the group because they saw an opportunity to learn and come together to share problems.

“If you can’t cope with your problems, you come in and share your problems with Vanessa and the other women. They will advise you, or maybe refer you or seek help for you,” Malebo says.

Malebo managed to get temporary work through the Community Work Programme, which operates 223 placement sites across the country and in every municipality and metro. It was established to provide an employment safety net to the unemployed and underemployed by offering them a minimum number of regular days of work each month. Malebo earns R780 to sweep school classrooms eight times a month. Her husband was hospitalised with severe depression following a job loss. “He lost his mind and was hospitalised for three months. By the grace of God, he recovered and is on medication,” Malebo says.

Related article:

Reynolds says the effects of Covid-19 have increased the burden of care on women. “They are expected to be the primary healthcare givers for their families. They are the ones responsible for putting food on the table for their children and the extended family. Many of the elderly women are also substitute parents to their grandchildren and are responsible for helping them with their homework, yet they are barely literate. All this leads to mental health issues, and many women are crumbling under the pressure for it is becoming harder and harder to juggle the various roles that have been thrust on them.”

A study on the impact of job loss and mental health showed that adults who lose employment were likely to have high levels of depression. Women were more likely than men to experience a higher average increase in mental distress when they lost their jobs.

After HIV and other communicable diseases such as TB, mental health and nervous system disorders are the third highest contributor to the burden of disease in South Africa. But mental disorders are far less likely to be treated than physical problems, even though they can often be more debilitating. Existing mental health services need to be scaled up and adopted to the local context.

TWC is an example of how mental health services can be adapted to local contexts. Even though the provision of mental health services has been decentralised and moved to communities and district hospitals, the scale of services remains inadequate. Mental health services in South Africa have been significantly underfunded. One of the stated objectives of the South African Declaration on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases is to increase the number of people screened and treated for mental illness by 30% by 2030. The effects of the pandemic on mental health make this objective even more urgent.

*Not her real name.

This article was produced by the Africa Women’s Journalism Project in partnership with the ONE Campaign and the International Center for Journalists.