Women are on their own in unequal South Sudan

Though the assault on one of the country’s top women footballers caused an outcry that reverberated outside its borders, the government has remained silent on the matter.

Author:

14 December 2021

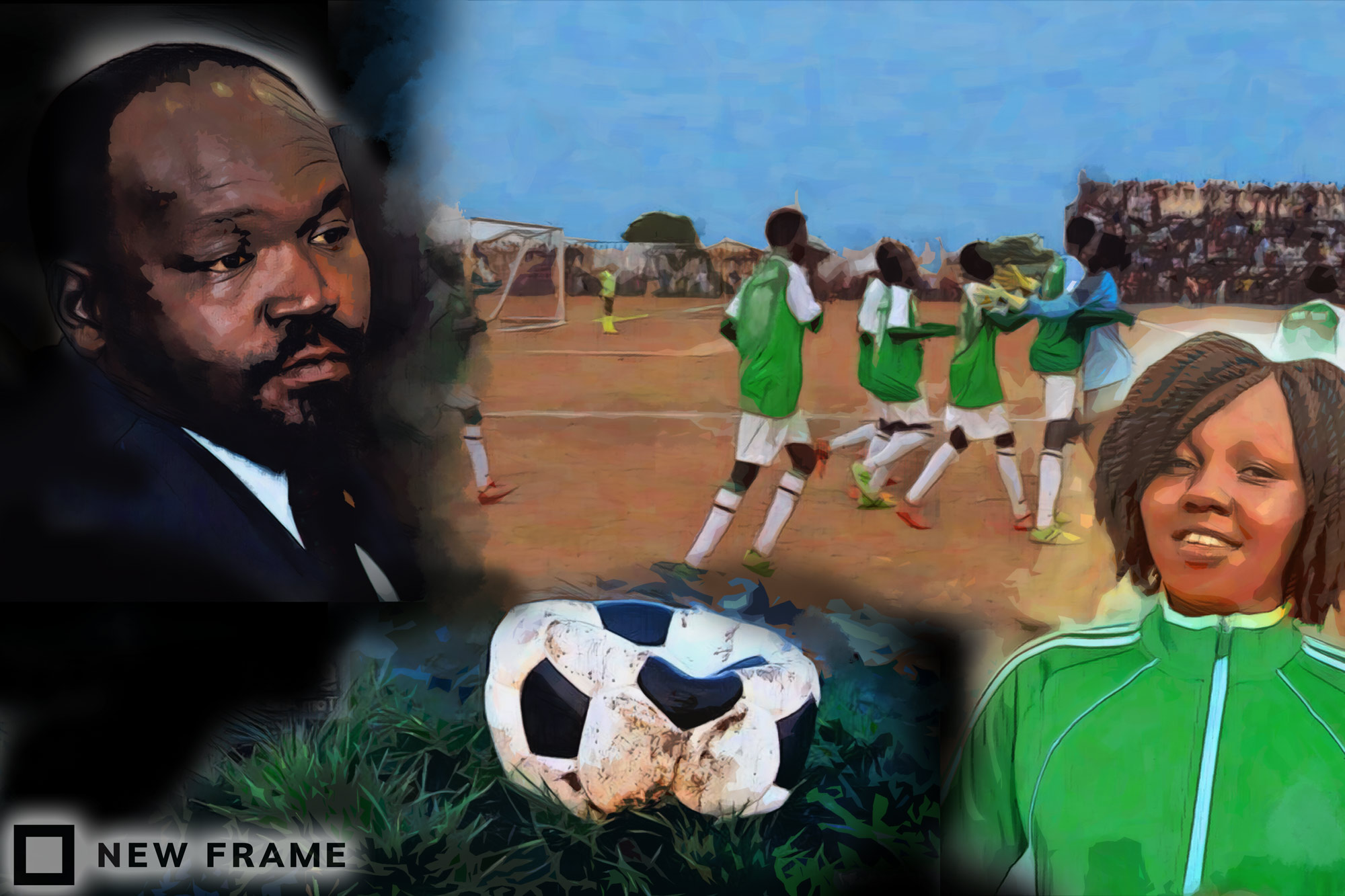

The ambitious project of women’s football in South Sudan, with plans to become a force on the continent while using the popular sport to address the poor treatment of women in the country, was always going to be an uphill battle in Africa’s youngest democracy.

South Sudan’s greatest challenges lie in changing discriminatory attitudes towards women and girls, and replacing biased social norms with constitutional rights for everyone. At best, this year the football project shone the spotlight on the many challenges women face in South Sudan when it magnified a crime that would otherwise go unnoticed or hardly cause a stir.

The misogynistic nature of President Salva Kiir’s government was unmasked by its vehement refusal to punish Peter Mayen Majongdit, South Sudan’s minister of humanitarian affairs and disaster management. This was after Majongdit’s own party, the People’s Liberal Party, terminated his membership because of his violent conduct.

Majongdit rose to international infamy for storming the pitch on 17 April to drag his wife Aluel Garang, one of the country’s most talented footballers, off it. His alleged physical assault of Garang on 26 July caused a further outcry that put pressure on the government to distance itself from him.

Related article:

The South Sudanese Women Intellectuals Forum, a non-profit organisation that advocates for a free, just and equitable society, condemned the beating and stabbing of Garang in the “strongest possible terms”. “The women of South Sudan cannot stand by and watch quietly as such acts are perpetrated by those who are supposed to represent us as a country,” it said.

On 9 August, women’s rights activists, all dressed in black, staged a protest demanding Majongdit’s sacking as minister. While presenting a strongly worded petition to Minister of Gender, Child and Social Welfare Aya Benjamin Warille, they brandished placards bearing messages like “Justice for Aluel”, “Gender-based violence is a pandemic”, “Enough is enough” and “Aluel’s safety should be a national concern”.

Instead of being punished, Majongdit was recently welcomed to the National Assembly, much to the dismay of rights activists and the country at large. “They don’t want Aluel to play again. She is supposed to play in the national team, but her husband doesn’t want her to play,” said Moses Zakaria Ngor, Garang’s former coach at Aweil Women FC.

Not a magic solution

Majongdit’s conduct and the government’s reaction showed that football is not a silver bullet that will bring about gender equality. But putting the spotlight on such matters and pushing the public to call for action are small steps in the right direction.

“This is the worst form of violence that any other person can talk about. If somebody has to reach that far … that person is capable of taking your life away,” gender activist Grace Akon Biar said in reaction to a photograph of a bruised Garang that surfaced following her assault. “We hope that the parents of Aluel will be able to make a bold decision of even taking the man to court and the two can separate.”

Despite several attempts, important role players, including staff of the women’s national team, refused to speak on the matter.

Opening up to Juba-based broadcaster Eye Radio just after the attack, Garang’s uncle, Deng Garang, said “as a family we are not happy. We are so emotional and this is unbecoming. Aluel is now in Kuajok and she is still locked in and has no access to us. She doesn’t have a phone because her phone was destroyed by Peter Mayen.”

Related article:

Garang returned to her husband 17 days after the attack. “Hi guys, this is Aluel Messi, Aluel Mayen. I am happy now. We resolved our problem with the family. And now we are happy. We are in our home… Everybody is happy,” she said on 12 August in a video that surfaced on social media.

A day before the video was posted, however, a relative said Garang was back in Aweil following an amicable agreement to get a divorce. “Only abusers would celebrate a victim going back to her abuser, because that affirms to them that violence against women is not a crime and that they too can get away with it,” said women’s rights activist Aluel Atem.

According to Biar, a lot needs to be done to combat the scourge of domestic violence in South Sudan. “Social norms tell the girl not to report violence that she goes through. That means when a girl gets beaten or goes through physical violence, physical abuse, sexual abuse, she has to keep quiet. And that is the main cause of it,” Biar said.

Garang’s assault, and the government’s reaction to it, showed that women are on their own in South Sudan. It’s going to take a lot more than football to change things for the better.