Wisdom and fire from jazz’s ‘midwife generation’

Postapartheid’s musical pioneers are back with new albums and old concerns after spending much of lockdown teaching, learning, collaborating at a distance and creating.

Author:

17 December 2021

“Ours is the midwife generation, between the old school and the youngsters,” says saxophonist and composer Steve Dyer.

Dyer is discussing the musicians of the 1980s and 1990s, whose explosion onto Nelson Mandela-era stages and music stations first declared the postapartheid South African jazz renaissance. Their music included McCoy Mrubata’s 1989 London-recorded Firebird, Zim Ngqawana’s 1996 San Song, Paul Hanmer’s 1997 Trains to Taung with Zimbabwe-born guitarist Louis Mhlanga, Moses Molelekwa’s 1998 Finding Oneself, and his own 1989 Zimbabwe-released Southern Freeway.

Perhaps we need reminding that such a renaissance is possible after the devastation wreaked on the live music scene here by the pandemic, lockdowns and official neglect. It is striking how many of the graduates of that first wave are back with fresh music in the crop of new album releases in late 2021 – and how many of their worries about the music scene would have struck a chord even back then.

Dyer released his 13th album as leader, Revision, in mid-September. Mrubata and Hanmer, alongside Ngqawana’s longtime pianist Andile Yenana, can be heard on the saxophonist’s Quiet Please, out in late October. Trumpeter Feya Faku (who worked with Ngqawana, Mrubata and more) released two Swiss-cut albums, Live at the Bird’s Eye and the drum-less trio Impilo, in the same month.

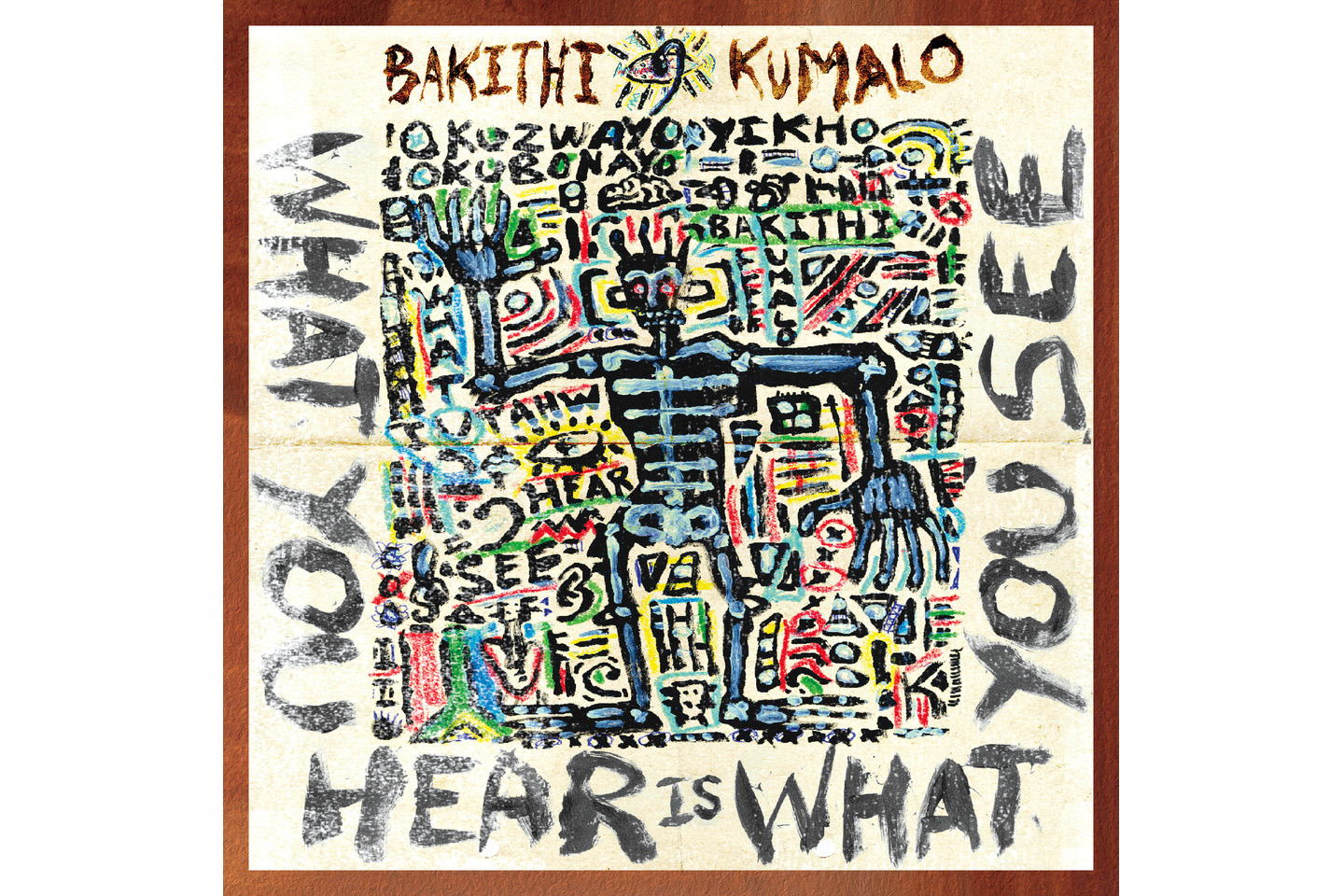

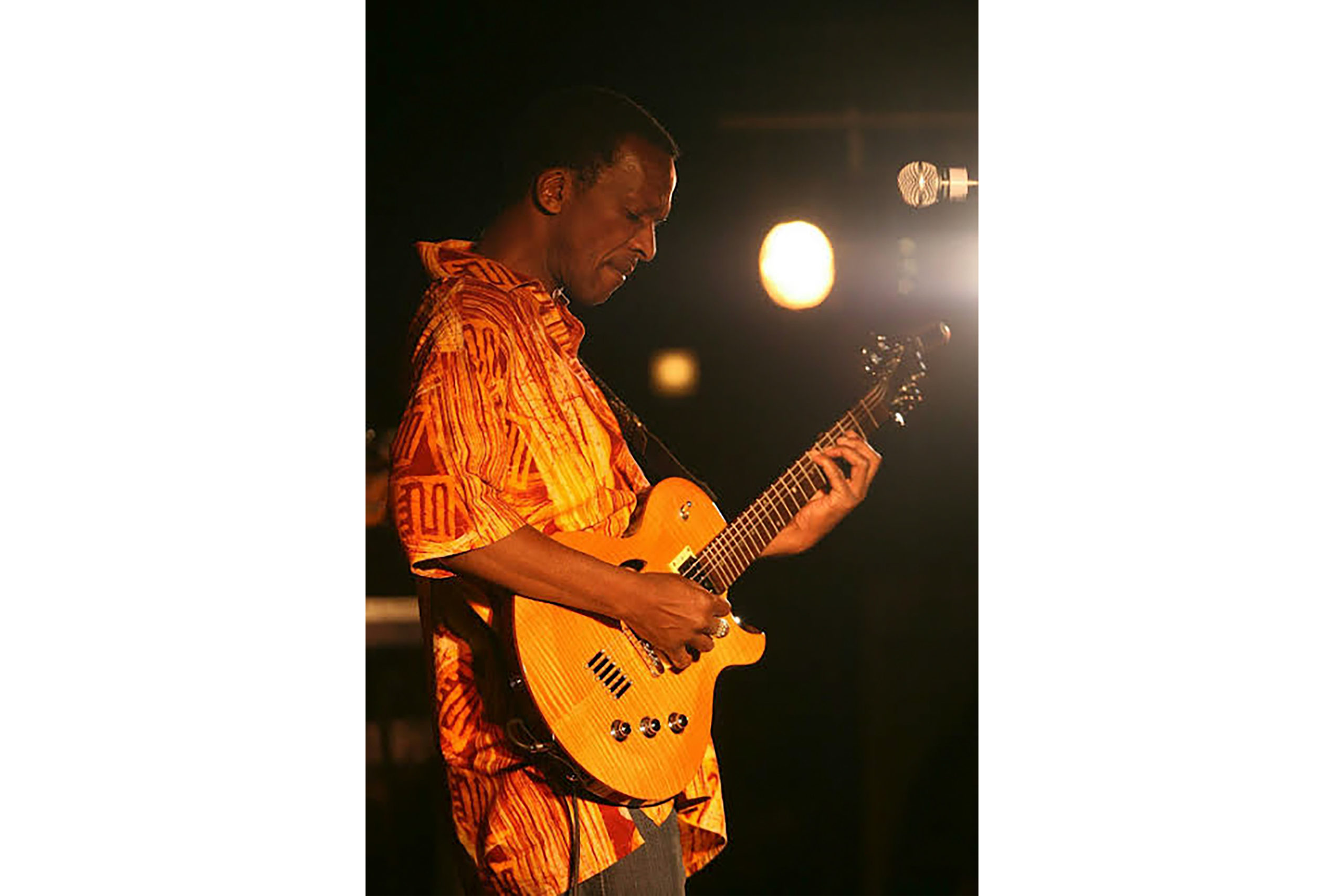

Bassist Bakithi Kumalo, who played with Mrubata on Firebird (but is now based in the US), released What You Hear is What You See in November. One of Ngqawana’s bass partners, Herbie Tsoaeli, has just launched his long-awaited second album, At This Point In Time, featuring both Yenana and Ngqawana’s regular drummer, Ayanda Sikade, while that latter’s own sophomore release, Umakhulu, arrives in mid-December.

Mhlanga, meanwhile, is readying not one but two releases for 2022: a solo album and the digital release of a 2002 Bassline recording, featuring Tsoaeli on bass and Yenana on keys.

For even the youngest of that generation, it is more than a quarter of a century since they started in music. Four of them, Dyer, Kumalo, Mhlanga and Mrubata, reflect on their experiences and the changes they have witnessed.

Ever growing, ever learning

Nobody has stood still. Growing new approaches, skills and sounds has been a necessary constant in all their lives. It continues today.

“For me,” says Kumalo, “it’s been learning, learning and never stopping.” The new album, his sixth as leader, involves diverse African instruments including the North African gimbri bass, and new collaborators such as Kenyan pianist Aaron Rimbui and Ugandan spoken-word artist Tshila. “But it’s not just learning new musical things. We also learn to be teachers: to our students and our own kids. And from that, you learn to be truthful, in what you say and in your music.”

Everyone has transitioned from simply playing in bands to playing more fluid roles: in diverse ensembles, as solo artists (“I’m allowing the voice of the guitar to sing more now,” reflects Mhlanga), composers, and in Dyer’s case – because he now also runs the Dyertribe Studio – in production. Mrubata has been assembling a powerful collective of collaborators. Rather than trying to do everything himself, he now calls on musicians such as trombonist Jabu Magubane, singer Hlubi Kwebulana and baritone player Gareth Harvey as arrangers; Luyanda Madope, Viwe Mkizwana and Yenana as producers, and more.

In the messages of their music, less has changed. Music for Mhlanga has always been “food for life … continuous positive creation [that] helps the world we live in to grow”. Kumalo’s music is “a medium to tell the African story … on the new album my bass is a speaker for the people, showing the world who we are”. Mrubata “will forever try to do my bit to raise my voice about injustices, corruption and to encourage people to do the right thing”. Dyer is focused on pan-African human cooperation, making “music that celebrates African riches and gives voice by extension to alternative and globally marginalised … ways of being”.

Such commitment to Africa and emphasis on working together, they all say, is part of what came down from their predecessors and teachers. Possibly because we’re talking immediately after his death, the late saxophonist Barney Rachabane gets many accolades. Dyer recalls Hugh Masekela in Botswana remarking how Rachabane made him feel he needed to practise a lot more; Kumalo found his presence both on and backstage “like a bright, beautiful warm sun; he was so loved”. Kumalo names others, including bassist Sipho Gumede: “He showed up on time; he was serious and disciplined, and he told us, ‘Hey, you must have your own sound and identity.’”

Reflections in time and sound

When they reflect on their long careers, collaborations and the support of others, not individual achievements, form the highlights.

Sometimes it is intensely personal. For Mrubata, it is always “being on stage with my best friend Paul Hanmer, and especially 2018 when we celebrated our 30 years of friendship and music partnership”. That comes ahead even of appearances at iconic American and European venues, and receiving the 2018 Kennedy Center gold medal award. Kumalo says while “being in the same studio with Herbie Hancock [was] amazing – and terrifying” and the invitation to play on Paul Simon’s Graceland “has to be a highlight because it was the opportunity I never expected [and] the chance I had to take”, all that is eclipsed by reconnecting with his Durban-based sister, Nomvula, whom he had never known before. Nomvula died from Covid-19 complications in 2020 and the whole album is dedicated to her memory.

Mhlanga and Dyer’s highlights have been more process-oriented: exploring music from elsewhere and the people and ways of knowing and living they represent. The guitarist has drawn from working with other instrumentalists and their sounds. He counts them off: “Accordion, mandolin, mbira, flute, kora.” The saxophonist – who’s recently been delving into Mogobe Ramose’s philosophical study of ubuntu – ruefully admits that he’s “still searching and probably will be for as long as I’m a musician for that one ‘magic moment’”.

When they look at the South African jazz scene today, all four are heartened by the talent they see and the fresh ideas they hear. “Most of that great music, though,” says Mhlanga, “fails to reach the doors of the radio stations. [Most of what is played] is sampled and computerised with no inspiring messages in the lyrics. Our radio presenters’ hands are tied on commercial stations; they aren’t free to play the real stuff.”

That problem goes further than airplay, however. Mrubata observes that the standard of music education is high, “but sometimes the young ones are stacking a lot of ideas together to sound ‘deep’, when they’re already talented, hip and have great ideas that they might be suppressing because they want to sound [like somebody else’s idea of] hip. I’d encourage them to sing more – not necessarily literally, but the music needs to be lyrical and straight from the heart.”

Dyer says he’s learned a lot from the new ideas younger players generate, but at the same time, “sometimes, they don’t have the same grounding – eg in marabi traditions – that some of our generation take for granted”. He sees a lot of imaginative music at his studios, and the assertion of startlingly fresh African identities. But he says players have often “done this outside of tertiary institutions, most of which have curricula that seriously undermine the South African jazz tradition”.

Kumalo is equally saddened by the absence of the South African jazz tradition from schools and colleges. “People like Kippie [Moeketsi], Duke Makasi, Winston Mankunku had our roots, our tradition. Today, you’ve got everything in the palm of your hand: you just click on the computer – but mostly you won’t be able to click on that! There’s a lack of places and resources to learn about it – we need an SA music museum. My culture helped me survive – and my aim would be to come back home and find funding to put our music back in the classrooms. There should be schools named for Allen Kwela and Barney Rachabane! University students learn John Coltrane, and that’s wonderful – but where’s Dudu Pukwana? There’s no story being told.”

It’s a remote hope that government structures will help. “Musicians have to do it for themselves,” says Kumalo. That became clear when Covid-19 hit all South Africans hard, and for performers, support was late and limited. The impact on musicians was emotional too. “Music is a vibration that’s meant to be shared,” says Mhlanga, “and when there’s no one to share it with, that affects the bearer of the vibration too.”

Creating in the now

All four artists kept creating during Covid. Mhlanga developed and recorded solo compositions; Dyer, with his studio, was able to create a film soundtrack for the Zimbabwean movie Shaina; Kumalo composed, taught and worked at a distance; Mrubata learned new skills. They know many peers who were doing something similar: the new albums emerging now are partly a result of that lockdown creativity. Some, including Mrubata’s Quiet Please, have tracks alluding to the experience. “It made many of us reflect and take stock,” says the saxophonist. “We learned new tricks and skills – for example I learned the Bandlab online app. I think post-Covid we’ll incorporate some of that, and continue live streaming concerts.”

But they are all aware that many friends in music lost too much to retain the same hope. Dyer thinks it will take something very different from current structures to support rebuilding. “During the change to a ‘democratic’ dispensation [we inherited] functioning organs of state – but there was never any … restructuring. Funding for the arts has mostly taken a bloated, top-down approach … with no long-term vision recognising the economic and social benefits culture (in this case music) can bring … working from the ground up.”

Given all that, what message would each veteran send to their younger self, all those years ago? “Life’s unpredictable,” says Mrubata. “Always prepare for the worst but stick to your goals.” Perseverance is also on Dyer’s mind. Although “the industry is a bitch, stay true, stay the course and never stop learning – music embodies so much that’s positive”. Despite the oppressions of apartheid in the 1980s, Kumalo agrees: “I’d tell my younger self to hold on to the experience – you’ll be glad you did it, and you’re learning from it.”

All of which is reassuringly sensible and Apollonian. But where, amid all this rationality, is the Dionysian side of music-making: the wilder spirit that inspires players to choose such a risky life in the first place? For that, the last word belongs to Mhlanga. “Advice to my younger self? When you enter the music space, you’ve signed a contract with the gods of fire to use that flame. If you don’t use it, it’ll burn you.”