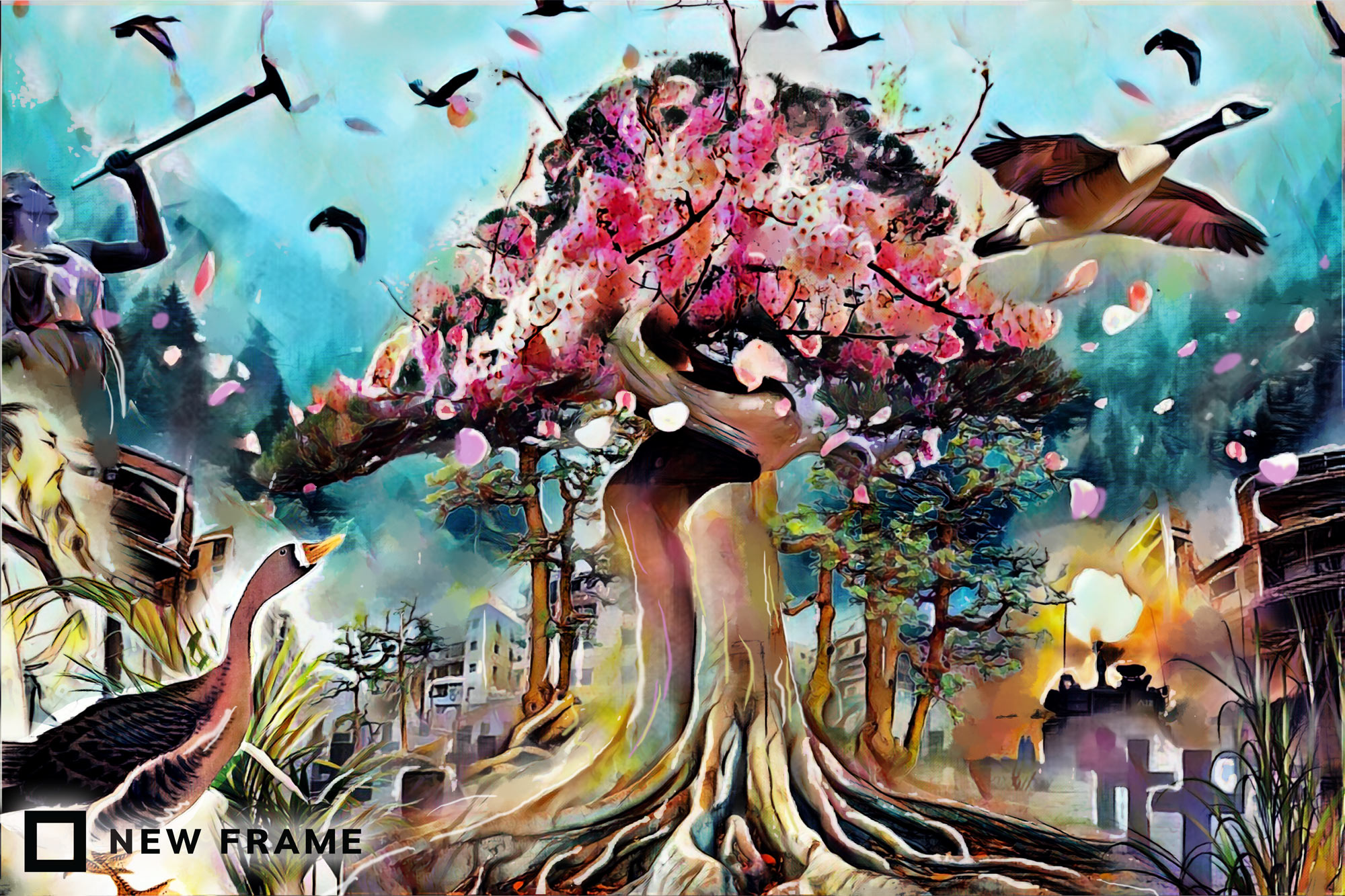

Will nature’s song ring out?

In Text Messages this week, there is a hope that the 26th climate summit in Glasgow will bring about a spring as exalted by the greatest poets to follow the winter of climate catastrophe.

Author:

9 September 2021

The most poignant harbinger of spring – in English, at any rate – is Shelley’s exclamation and question at the end of his Ode to the West Wind:

The trumpet of a prophecy! O, Wind,

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?

Implicit in the death of the old year, winter, is the promise of the new, spring. On the South African Highveld, winter took its annual biting farewell with a cold blast at the end of August, just as the calendar was edging thoughts and hopes towards warmth, green shoots and blossoms. That intermezzo, the seasons suspended, brought to mind a poem by great American poet WS Merwin, perhaps the finest poet writing in English today.

Clear Sound

Cold spring morning remembering

fewer birds now but their songs ring out

through the mist and the young leaves

that have never seen anywhere else

the songs rise out of themselves knowing the way

no words for before and after

and the singers nowhere to be seen

That is from Merwin’s superb volume The Moon Before Morning (Bloodaxe Books, 2014), in which he has a conversation across 12 centuries with Po Chü-I, the Chinese master poet who lived from 772 to 846 CE. Chü-I fell into imperial disfavour more than once and was exiled. The first time was because “in a series of poems he had satirised the rapacity of minor officials and called attention to the intolerable sufferings of the masses”, writes Arthur Waley in his One Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (Constable, 1918).

Related article:

During one of those exiles, Chü-I wrote Releasing a Migrant “Yen” (Wild Goose), about a wild goose from the north, lost and adrift in the south, yearning and searching for home – just as was the poet, also a northerner. Boys caught the goose and took it to market for sale. There, in Waley’s beautiful translation:

I that once was a man of the North am now an exile here:

Bird and man, in their different kind, are each strangers in the south.

And because the sight of an exiled bird wounded an exile’s heart,

I paid your ransom and set you free, and you flew away to the clouds.

But the poet worries about the goose and warns it to avoid the war-ravaged northwest, with its soldiers of the imperial army and boys of the rebel army, if it reaches home.

The brave boys, in their hungry plight, will shoot you and eat your flesh;

They will pluck from your body those long feathers and make them into arrow-wings!

Related article:

So ends the poem. Merwin, more than a millennium later, in the final lines of A Message to Po Chü-I, writes:

I have been wanting to let you know

the goose is well he is here with me

you would recognise the old migrant

he has been with me for a long time

and is in no hurry to leave here

the wars are bigger now than ever

greed has reached numbers that you would not

believe and I will not tell you what

is done to geese before they kill them

now we are melting the very poles

of the earth but I have never known

where he would go after he leaves me

Celebrated and beloved Sufi mystic and poet Jelaluddin Rumi (1207-1273 CE) would have sorrowed over what is happening today to his home city. Rumi was born near Balkh, now in Afghanistan, then on the eastern verges of the Persian Empire. But to return to the theme of spring, mingling the joyous with the wise, here is Rumi on that season. Note that it’s a northern spring, hence the reference to death in December. The vivid translation is by American poet Coleman Barks from his authoritative and magisterial Rumi: The Big Red Book (HarperOne, 2010).

Trees

Spring, and no one can be still,

with all the messages coming through.

We walk outside as though going to meet visitors,

Wild roses, trilliums by the water.

A tight knot loosens.

Something that died in December

Lifts a head out, and opens.

Trees, the tribe gathers.

Who has a chance against such an elegant assemblage?

Before this power,

human beings are chives to be chopped,

gnats to be waved away.

In Shelley, Merwin, Chü-I and Rumi, humans are evanescent, nature eternal. That is the right way. If only those at the forthcoming COP26 climate summit would pause and smell the wild roses Rumi writes of, see the “elegant assemblage” of the tribe of trees, look to the skies and catch the flights of migrant birds, and listen for Shelley’s trumpet of a prophecy: that spring is coming and, with it, the better hopes of humankind.