When the city of gold bled red

In 1922, Johannesburg’s white workers united on a scale not seen before or since, unleashing violence against Black miners and destroying their potential to become an organised force.

Author:

4 March 2022

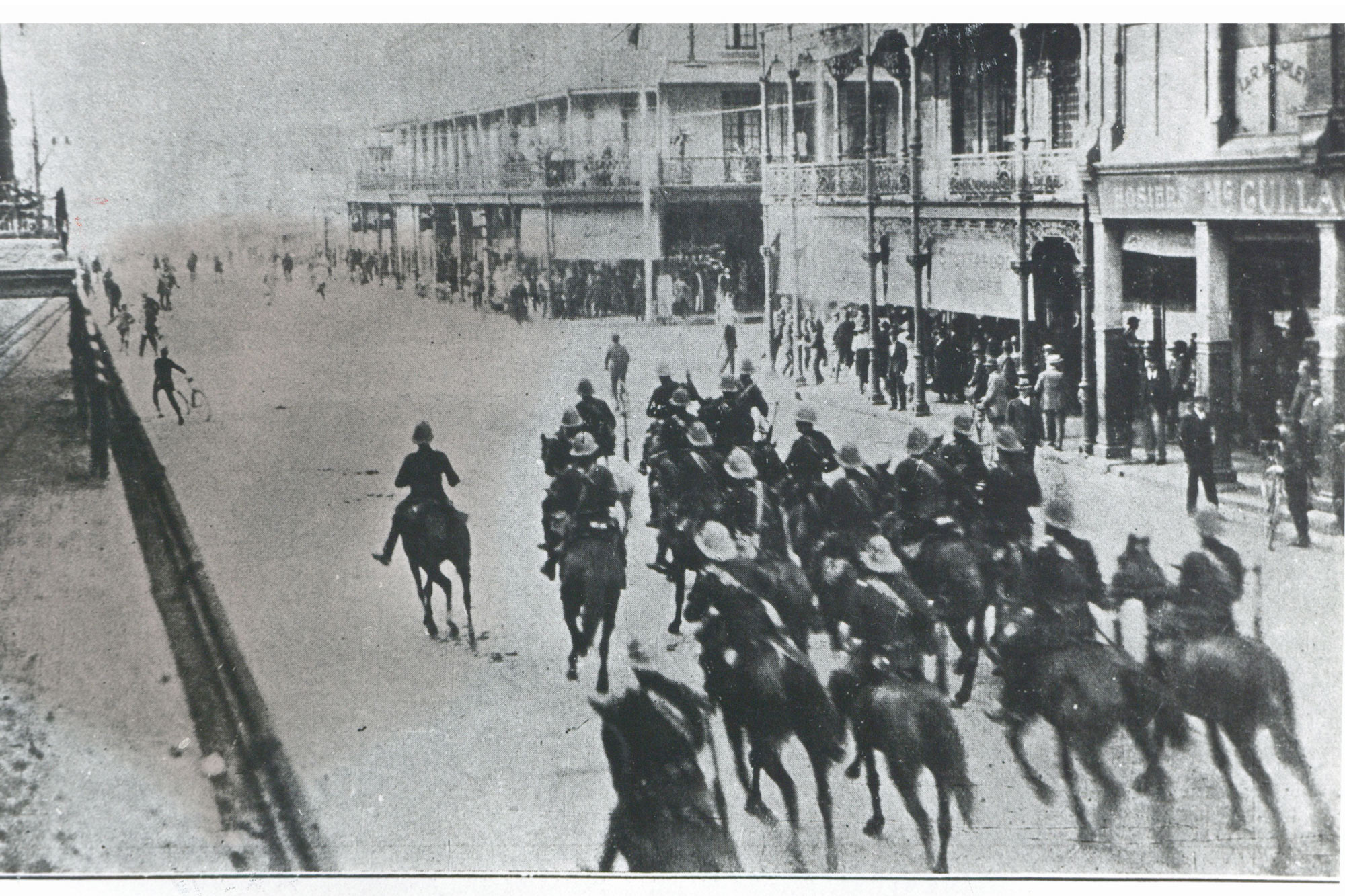

A century ago, on Monday 6 March 1922, a general strike was declared in Johannesburg, setting off a rebellion that left the young city’s streets drenched in blood. During the few ferocious days that followed, gangs of armed white workers carried out pogroms against their African counterparts until martial law was declared.

Martial law allowed prime minister Jan Smuts to mobilise tanks, artillery and bomber aircraft against the rebels – almost a decade after Winston Churchill had proposed using aircraft in the occupation of Somaliland (Somalia) and nearly a year after private white pilots had slaughtered Black American residents in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

At the time, coal workers in the Lowveld had already been on strike for 65 days and miners on the Witwatersrand for 55. But a more consequential few days than those between the declaration of the general strike and then martial law can scarcely be imagined. They have shaped the city, and country, for a century since. A historian from the University of the Witwatersrand, Keith Breckenridge, has said that for “anyone who is interested in the building of a just society in contemporary South Africa” the social consequences of what came to be known as the Rand Revolt “weigh upon us like Sisyphus’ stone”.

Johannesburg in 1922, by then the beating heart of global gold production, was at the eye of a world historical storm that left it vulnerable to change. The socialist overthrow of the empire in Russia five years earlier had set off a wave of revolution at the same time that an inflationary crisis at the end of World War I had impoverished workers the world over.

On Johannesburg’s gold mines, white workers were further angered by the Chamber of Mines’ attempt to open jobs reserved for whites to cheaper, semiskilled Black replacements. Their defence of racial privilege came after years of impeding the organisation of African workers and is part of why Breckenridge has called them “much more militantly racist than they were militantly socialist”.

Visible traces

One can still trace the Rand Revolt, however faintly, in many places across Johannesburg’s short but crowded history. Visit the public bathrooms in Fordsburg and, even today, you will see walls marked by the gunfire of 1922. Or, wade into the many archival records telling the city’s story. There you might come across a series of cables sent from the heart of the rebellion to one JL van Eyssen, a mining engineer in Cape Town taking part in negotiations between Parliament, the Chamber of Mines and the authorities in Johannesburg.

The first of these cables was sent on 22 February explaining to Van Eyssen that the proposed cuts to the wages of white colliery workers in the Lowveld would save three pence per ton of coal, a considerable annual saving of £35 000. Five days later, the cables claimed that the position of Johannesburg’s striking gold miners had been considerably weakened by the “stronger attitude of police”. The city’s ruling classes could clearly see an end to the unrest, and Van Eyssen was informed that “various strike leaders continue to approach me making suggestions for settlement, all of which indicates distinct weakening strikers position”.

By 1 March an arrogant Chamber of Mines, which was by then importing union-busting strategies from the United States, rejected the proposals of the South African Industrial Federation, “stating definitely that no basis other than that laid down by [the Chamber] can possibly be accepted”.

The cables were by now dripping in the language and logic of profit, noting that the collieries would rehire a fraction of the workforce they had employed before the strike, which had “opened managers eyes to superfluity of many men”. Two days later, Van Eyssen was informed that workers were “tumbling over themselves to get back” to work.

The tune changes

But by the time the general strike was declared on 6 March, and the gold mines were accepting 130 scab workers out of 200 applications, the confidence of Johannesburg’s elite had all but evaporated. “Sabotage advocates now apparently in control,” the cables read, “and redoubled efforts towards violence.”

By the next day, when Van Eyssen had received reports of a “very great increase in attempted intimidation”, gangs of workers were preventing the delivery of bread, shutting down businesses and stopping buses and taxis transporting scabs to the mines. Dozens of armed white men stalked working-class neighbourhoods like Ferreirastown and Vrededorp, shooting at African people on the street. In the dead of night, the rebels bombed a mine in Primrose with dynamite.

By 8 March, with reports that “greatly increased terrorism threatens most serious effect on position of mines,” more than 100 scabs were joining the mines every day, protecting shaft heads and other infrastructure with guns against the revolutionaries, who also tried to blow up the city’s railways.

But control over the rebellion had already passed from workers into the hands of the rural Boer commandos that had arrived in Johannesburg to bolster their cause. Early in the morning, one such commando attacked a group of African workers, taking their picks from them and using the tools to attack them. The workers narrowly escaped with their lives after stoning the commando in retaliation. Another rifled commando attacked a mining compound in Primrose on the east of the Rand, killing four African workers and wounding another 16 (after the police arrived, the commando was allowed to move off without an arrest being made), while the cables reported that “natives were killed and fourteen injured near Vrededorp”.

After the commandos began to terrorise the city, Van Eyssen received a cabled vindication of mine bosses’ refusal to further engage with their workers: “The Chamber performed public service in fighting revolutionary Soviet which it must now be plain to everyone intended dominate country.”

By the time martial law was declared on the Witwatersrand on 10 March, amid further reports of the “cold blooded murder of natives”, Johannesburg was under serious threat of being overrun by revolutionary forces. Many of the cables sent to Van Eyssen had reverted to code. The first line of one read “GIXYGEDMYF NAXUHANYNY TIKSIOTRYC DUTWAGEDYG LURUCRYTKO”.

The Rand the revolt made

In the days that followed, Smuts ordered first shrapnel and machine-gun fire and later the aerial bombing of working-class neighbourhoods housing the Rand’s white revolutionaries. It remains the only time that the South African military has dropped bombs on their own territory.

Suppressed and defeated, the white workers turned their anger on African civilians, murdering and mutilating. The strikers murdered 150 African people during the course of the Rand Revolt. Four rebels were ultimately sentenced to death, two for killing innocent Africans. (Smuts released the hundreds of others who were arrested and convicted before the 1924 elections.)

The African workers against whom much of the violence during the Rand Revolt had been directed had recently won unprecedented organisational ground. Two years earlier, 70 000 of them had walked off the job in a week-long and violently suppressed strike. But, in a piece of 1924 legislation designed to appease the white workers and social forces fuelling the Rand Revolt, Smuts’ government barred African workers from the resolution of workplace disputes, driving a nail into the coffin of organised African labour just at the moment when it seemed African workers might escape it.

1922 was the last serious worker-led threat to Johannesburg’s social order. At the height of their revolutionary potential, however, the city’s white workers killed African workers in cold blood. And, in their defeat, they condemned African workers to the worst-paid jobs for generations to come.