When the bonfire came for the library

In this week’s Text Messages, the wondrous but troublesome book illustrates humans’ perplexing capacity for both inspired invention and thoughtless destruction.

Author:

22 April 2021

There is no firm date for the invention of paper, although certainly the first paper was rather less sophisticated than the material we know now. But there is no doubt that its origins lie in China, with perhaps a seminal date being 105CE, when the high official Ts’ai Lun standardised paper as the writing medium for the imperial bureaucracy.

This administrative change resulted from the gradual accumulation of paper-making technique over a long time, and from Ts’ai Lun’s radical material innovation. Early Chinese paper manufacturers used the paper mulberry tree, its fibre soaked in water with wood ash to separate individual fibres. These were then poured on a wooden-framed screen made of either hemp or cotton and the fibres smoothed out by hand. After this, the screen was taken out of the water and left to dry. Repetitive and time-consuming, this process meant a good day produced only a dozen or so sheets.

Ts’ai Lun’s great leap forward was to introduce additional base materials: hemp, textile offcuts and scraps from fishing nets. Add to that bamboo screens later supplanting wooden frames and a craft became an industry.

For almost two millennia, paper was the repository of the past, the recorder of the present and the guarantor of the future, through histories, memoirs, treaties, banknotes, pamphlets, news sheets, newspapers, books, bonds and wills. It was the ultimate enabling medium, an inexpensive facilitator worthy of what was written on it.

But what if all those pieces of paper disappeared? The past and the present would be lost and all the promises about the future as well. It is a nightmare scenario.

All too often, large quantities of paper used for writing or printing have vanished. Most frequently they have gone up in smoke because paper and fire are not good companions. Brought into contact, one consumes the other. After flames gutter and die, ash is all that is left of the wondrous material that contained and conveyed thoughts and feelings in words consigned to its bright, hopeful surface.

Forever lost

That is the tragedy of the inferno at the University of Cape Town’s Jagger Library, destroying rare collections of books and manuscripts and so much of South Africa’s linguistic, cultural, anthropological and historical heritage. Much of the library’s holdings were not digitised – the contemporary world’s hedge against blazing disaster.

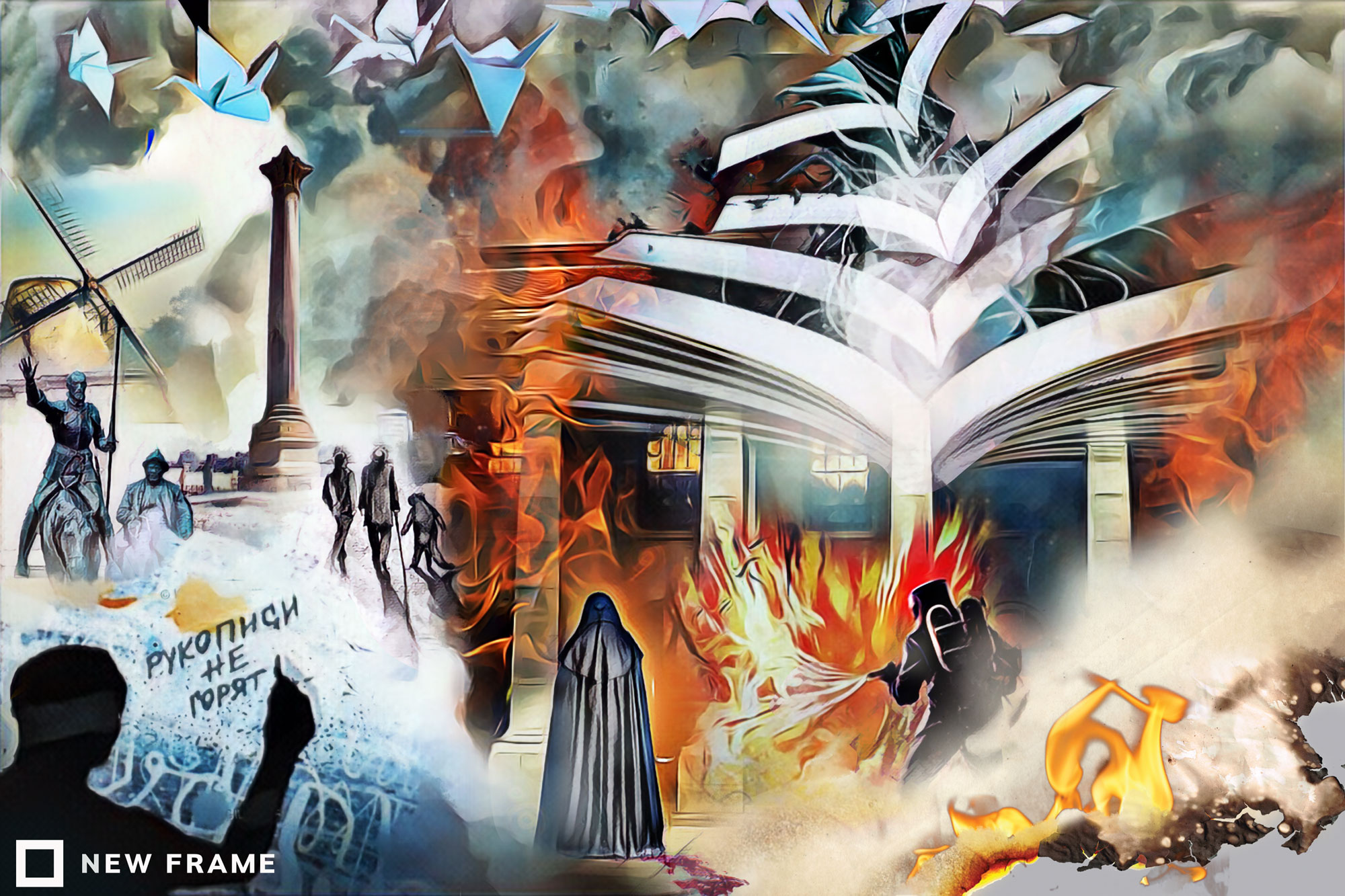

As storehouses of rapidly combustible material, libraries are particularly vulnerable to becoming bonfires. Sometimes their destruction is accidental, sometimes “an act of Nature” – neat designations that relieve humans of agency and responsibility. At other times, such as the burning down of the library of Alexandria in Egypt, human action is the cause: in that obliteration of the greatest library of classical antiquity, civil war was to blame.

Related article:

Perversely, humans seem to relish torching libraries. Library-burning became a collectivised variant of Nazi book-burning when student protests in South Africa targeted libraries at the universities of the Witwatersrand and KwaZulu-Natal. This sort of premeditated razing by fire is almost always a spectacular own goal, the consequences realised only after the event instead of before the first match is struck.

Even those who love and tend libraries have been known to set them alight. True, the example offered here is from a novel, The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco, the eminent Italian semiologist. This highbrow literary mystery and whodunnit, set in a medieval Italian monastery, follows the English logician and monk, Brother William of Baskerville, in finding the killer stalking this closed community.

Policing thought

If you have neither read the book nor seen the later film, you might wish to skip this and the next paragraph. Brother William works out what is motivating the murderer: striving to keep from and out of the world the “missing book” on comedy from Aristotle’s Poetics. In this Benedictine monastery, silence is a virtue to be practised, laughter a vice to be discouraged.

When the chief librarian learns Aristotle’s views on comedy, he tries to prevent others from absorbing what in his dour view are almost sacrilegious ideas. As scholar-monks nonetheless find or stumble on the book and read its contents, the old library-keeper does away with them. Identified as the murderer, he turns to conflagration as the last defence, setting the library aflame. Eco’s is an ingenious literary conceit, both finding something reputed to have existed and not, and “explaining” its absence from the Western literary canon.

Related article:

Book paper burns at 451 degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature which gave Ray Bradbury the title for his futuristic novel Fahrenheit 451. On its pages, an authoritarian state controls its citizens by feeding them a diet of saccharine and simplistic televisual material and by burning books. Firemen exist not to extinguish fiery situations but to create them: they are the state’s official book finders and book burners.

Perhaps the only amusing instance of books going up in flames is in Cervantes’ Don Quixote. Quite early on, after Don Quixote and Sancho have returned from their first foray into the wider world and Quixote is recuperating from his exertions, the village priest and barber sneak into his library. Those two, Quixote’s niece and his housekeeper believe the old man’s delusions and madcap adventures are inspired by books, dangerous things best disposed of.

Cervantes uses what’s on the shelves to indulge in a crisp and witty bit of literary criticism, and even inserts a mention of himself and his pastoral romance Galatea. But the family and the book haters are not to be denied.

Says his niece: “Better throw the lot of them out of the windows into the courtyard, and make a pile of them, and set fire to them, or take them to the backyard and make the bonfire there, where the smoke won’t be such a nuisance.”

Books – so bothersome, and all because of paper.