When bread and circuses lose their appeal

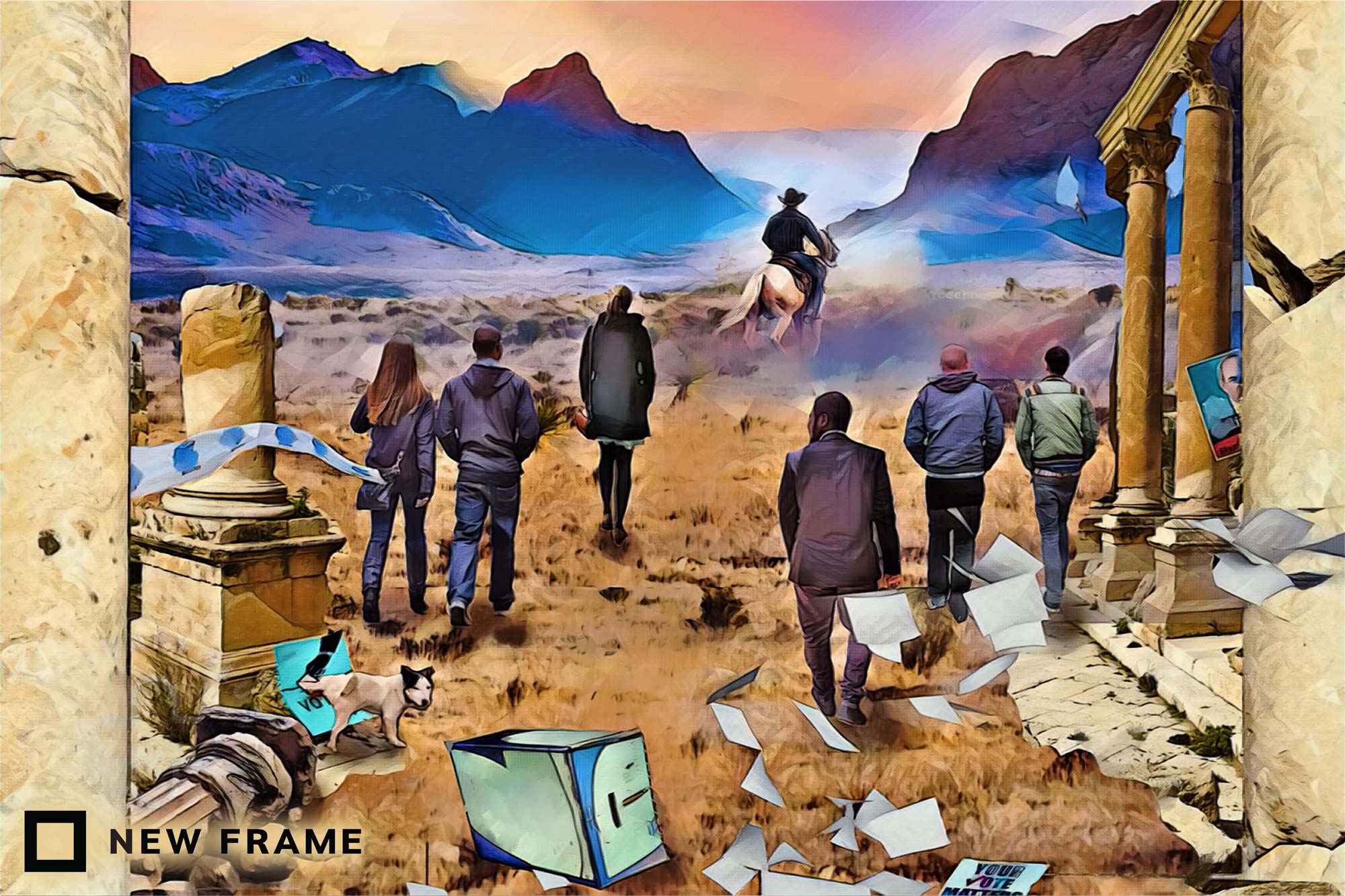

In Text Messages this week, democracy has been degraded and devalued, with elections providing only cyclical, cynical and farcical distractions. It’s time for the ballot box to go.

Author:

28 October 2021

Clear symptoms of a periodic malaise have begun to show themselves throughout South Africa. Men and women beseeching, cajoling and screeching at other men and women. Posters with lurid colour schemes, bearing the faces of men and women in fair imitations of the old West’s WANTED notices, are strung up on lamp posts and affixed to walls.

The airwaves, television screens and print media brim with hysterical, idealistic, earnest, clinical and coolly cynical talk of a national event, though beneath all these guises lie insincerity, self-aggrandisement and bafflegab. So important is this occasion that it has had assigned to it a public holiday, in a calendar already bursting with days off.

There is a quid pro quo, of course. The trade-off for the day off is that those so “enholidayed” seize the day and make their mark by signing X next to the candidate of their choice. Yes, alas, the election circus with its associated caravans of hopes, dreams and promises guaranteed to be broken, shattered and unfulfilled, is on the road again.

Related article:

Human nature is never so gullible as when in love or in the bosom of warmly embracing and tenderly caring election canvassing. No one can resist an incumbent candidate not seen since campaigning for the previous election now manifesting their presence in your very own area – proximate to you, at arm’s length, within reach. It’s a resurrection and a second coming second only to one other, and with a far more powerful trace of the miraculous: here, brothers and sisters, before our very eyes, is the embodiment of the ward councillor we have not seen these five long years. Praise be! Rumours of their death or disappearance clearly were grossly exaggerated.

And so it comes and so it goes. The innocent calendar is besmirched every few years by elections – national, provincial, municipal: the time, effort and cost ruinous and irretrievable. All to sustain the illusion of something called democracy, which has much to answer for, or perhaps its most ardent propagators do.

An adulterated ideal

If only democracy worked as defined in The Chambers Dictionary (10th edition, 2006): “a form of government in which the supreme power is vested in the people collectively, and is administered by them or by officers appointed by them”. This is the principle and practice of Greek demokratia – “people strength” – at work, of which more later.

However, what the modern world gets is the truncated form, so well defined in the South African Concise Oxford Dictionary (2002): “a form of government in which the people have a voice in the exercise of power, typically through elected representatives”. Note that “in which the supreme power is vested in the people” has here disappeared, in a pragmatic nod to realpolitik.

It was never meant to be this way. When “democracy” was being developed in the Greek poleis (“city states” for convenience), society and human nature were more sophisticated than they are today. The polis stood for a range of things: in some contexts, “the state”, in others, “the people”. The great classicist HDF Kitto summed it up with typically acute precision:

“Aristotle made a remark which we most inadequately translate ‘Man is a political animal’. What Aristotle really said is ‘Man is a creature who lives in a polis’; and what he goes on to demonstrate, in his Politics, is that the polis is the only framework within which man can fully realize his spiritual, moral and intellectual capacities.” (The Greeks, Penguin, 1951)

Related article:

Another factor is decisive in the misapplication of demokratia, polis and poleis to latter-day democracy, democracies and states. Kitto again: “Aristotle says, in his amusing way – Aristotle sometimes sounds very like a don – that a polis of ten citizens would be impossible, because it could not be self-sufficient, and that a polis of a hundred thousand would be absurd, because it could not govern itself properly.”

Democracy in our sense and practice of the concept is adulterated and unworkable. Yet it continues to be held up as the gold standard of governing systems. Held up, of course, by the ruling class and its associated elites – financial, institutional, media, academic and intellectual – to whom it is a boon most pleasing.

A cautionary tale

One needs to remember the caustic definitions of “politics” devised by the acerbic journalist and wit Ambrose Bierce (born in 1842 and thought to have died in 1914), the American West’s equivalent of Oscar Wilde. In Bierce’s The Enlarged Devil’s Dictionary (1906 and 1967), politics is defined as “A means of livelihood affected by the more degraded portion of our criminal classes. A strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles. The conduct of public affairs for private advantage.”

Bierce saddled his horse in 1913 and rode south to the Rio Grande, crossing into Mexico to cover the revolution there. He was never seen again, but a sense of what might have happened is provided in Carlos Fuentes’s marvellous novel The Old Gringo (El Gringo Viejo, 1985), which has as one of its epigrams Bierce’s “What they call dying/ is merely the last pain”.

Related article:

Perhaps the most eloquent arguments against democracy have been made in the novels of the now late José Saramago, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2006. To show those whom democracy really benefits, Saramago in Seeing (2006; Ensaio sobre a Lucidez, 2004) imagines an election in which voters deliberately return blank ballots. Stunned, the authorities of the unnamed capital city arrange a second vote. Even more ballots are left blank – up from 70% to 83%.

Panicked and unsure of how to deal with this subversive – but not illegal – challenge to their authority, the government resorts to a fascist retort. It declares a state of emergency, then flees the city, announces that the city is under a state of siege and plants a “terrorist” bomb that kills several. The strategy is simple and easy to see through: the fled government is saying to the recalcitrant voters, “This is what you get when you don’t vote for us to be in charge.” It would be hard to find a better summation of the devalued democracy now globally practised.

To the South African local government elections that take place on the public holiday of November 1, an old Arab proverb attaches: “The dogs bark but the caravan moves on.” The election farce will carry on until, like the voters in Seeing, people have the courage to make their disillusionment with democracy clearly visible. Not for nothing do they say that seeing is believing.