We must resist death-dealing borders

Borders are not merely barriers to movement. As inscriptions of colonial projects and power, intended to spatialise race and racialise space, they must be contested and rethought.

Author:

1 July 2019

Matamoros Banks, on Bruce Springsteen’s 2005 album Devils and Dust, opens with a body drifting in the Rio Grande:

For two days the river keeps you down

Then you rise to the light without a sound

Past the playgrounds and empty switching yards

The turtles eat the skin from your eyes, so they lay open to the stars.

The narrative winds back, to a man making his way across the Sonoran Desert to the Rio Grande, with the aim of crossing the river from Matamoros, in Mexico, to Brownsville, in Texas:

Over rivers of stone and ancient ocean beds

I walk on sandals of twine and tire tread

I walk on sandals of twine and tire tread

My pockets full of dust, my mouth filled with cool stone

The pale moon opens the earth to its bones

The man is making his way towards his lover:

Your sweet memory comes on the evenin’ wind

I sleep and dream of holding you in my arms again

The lights of Brownsville, across the river shine

A shout rings out and into the silty red river I dive

Last year American officials recorded the deaths of 283 migrants where the border follows the river that cuts between Matamoros and Brownsville. The figure for this year currently stands at 170.

Death on the river

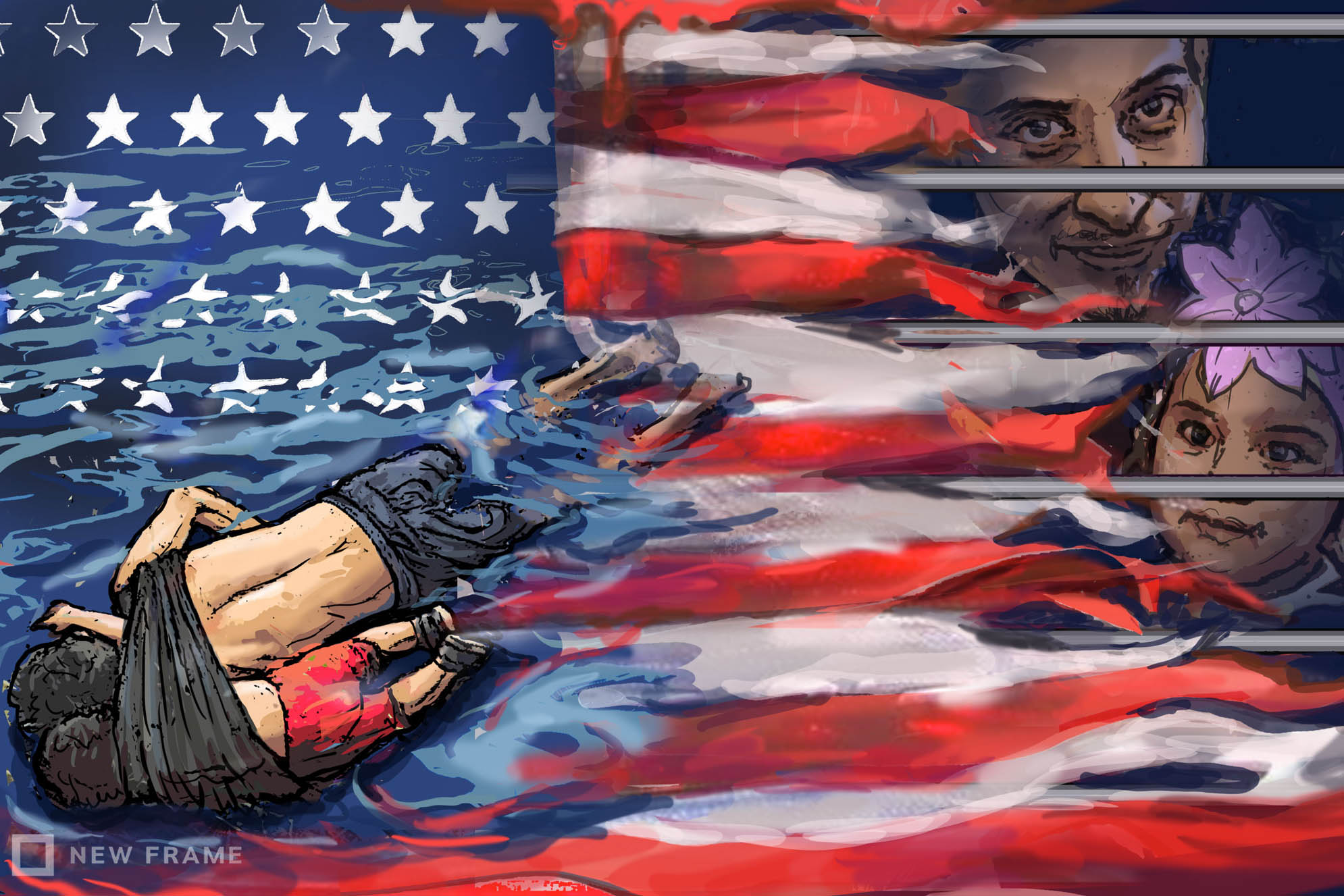

Last week, on 24 June, a photograph showing the bodies of a young father and his daughter, just a month shy of her second birthday, floating in the Rio Grande, rushed around the world. Like the 2015 photograph of the body of three-year-old Alan Kurdi on a Turkish beach, near Bodrum, the photograph of the bodies of Óscar Alberto Martinez Ramirez and Angie Valeria stopped the everyday traffic of cant and commerce for a moment.

Alberto was 25. He had been on the road with his wife, Tania Vanessa Ávalos, and their daughter for weeks before the river took them. They had left the impoverished and gang-ridden Altavista neighbourhood in San Martín, El Salvador and crossed through Guatemala and Mexico before reaching the Rio Grande. Tania saw the river take her daughter, and then, when Alberto rushed to her aid, her husband too.

Under Donald Trump’s regime the people that make it through some of the most lawless and violent territory on the planet, and then the desert, and then the river, must still face the Border Patrol. And then they must live with the constant threat of ICE, the armed and dangerous Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency of the federal government.

The Border Patrol is currently holding around 15 000 people. ICE currently holds more than 50 000 people in concentration camps. At least 12 000 children are being held captive, many in cages.

A recent report found that the conditions under which ICE detains people are appalling. In one instance 41 people were held in a cell built for eight, in another 155 people were in a room meant for 35. Children have been kept in vans, separated from their parents, for up to 39 hours. At least 24 adults and six children have died in the custody of ICE since Trump won the presidency.

Settler mentality

Trump, a leering, crude and brazenly racist man, is a particularly grotesque figure. But he doesn’t come out of nowhere. The United States is a settler colony born in the blood and fire of racial violence. From genocide to slavery, segregation and a profoundly racialised prison system that holds well over two million people today, the United States has always been a site of new freedoms for some at the direct expense of others.

The border that Trump wants to defend was drawn with violence and has always been policed with violence. Every colonial project inscribed itself into the earth with borders and zones, which created separate spaces for what were claimed to be separate kinds of people. From the city in the settler colony, to the political lines separating the earth into countries, race was spatialised and space was racialised.

Trump’s promise to ‘make America great again’ is a promise to affirm a racial hierarchy that is, in part, an ordering of space. And that project, the division of the world into races occupying separate spaces, was central to liberalism from the start.

The Declaration of the Independence of the United States on 4 July 1776 was made in ringing prose: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” But revolutionary liberalism’s concept of the count of the human among whom equality was a self-evident truth did not extend to the indigenous inhabitants of the territory that became the United States, or to the enslaved Africans who made it so rich.

The liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill was speaking with precision when he made it clear at the start of his famous 1859 essay, On Liberty, that “Despotism is a legitimate mode of government in dealing with barbarians”. Freedom was for some people, in some places, and funded by the devastation of other people, in other places. This has always been, and remains, the political logic of liberalism.

US despotism

Since its inception the United States has consistently acted to contain the aspirations of the people to its south, people it has assumed a right to dominate, and to subject to the most brutal forms of despotism. Some of the relentless attacks by the US on attempts to build democracy in Latin America and the Caribbean have intersected with our own drama.

In 2004 the US marines removed Jean-Bertrand Aristide, an elected president, from power in Haiti, with the enthusiastic approval of Tony Leon and much of the media here in South Africa. Aristide saw out much of his exile in Pretoria.

In 1973 the US backed a coup against an elected government in Chile. Augusto Pinochet, the fascist general who took power after the coup, was a loyal friend of apartheid.

But, in this moment, we must turn our attention to El Salvador, the country from which the young man and his daughter who drowned in the Rio Grande set out to reach Brownsville. In the 1980s the US state backed right-wing forces like Unita, Renamo and Inkatha in southern Africa with devastating consequences. In central America they backed the right-wing Contras in Nicaragua and a brutal military regime in El Salvador. For 12 years El Salvador was subject to unspeakable violation at the hands of US-backed death squads, including massacres, torture and scorched-earth tactics.

In 1981 at least 733, and possibly up to 1,000 unarmed civilians, were massacred in the village of El Mozote. American journalists who attempted to report on the massacre were subject to organised smears on their reputation. Silence was enforced.

In 2019, as capital and the US military continue to range freely around the world it is, above all, the border that sustains the neocolonial global order. Achille Mbembe, the intellectual who has done so much to take Johannesburg to the world in the realm of ideas, is correct to warn that borders are “becoming sites of reinforcement, reproduction and intensification of vulnerability for stigmatised and dishonoured groups”.

Borders are not simple geographic facts. They are material expressions of power, and sites of struggle.