Violence against women and the future of the past

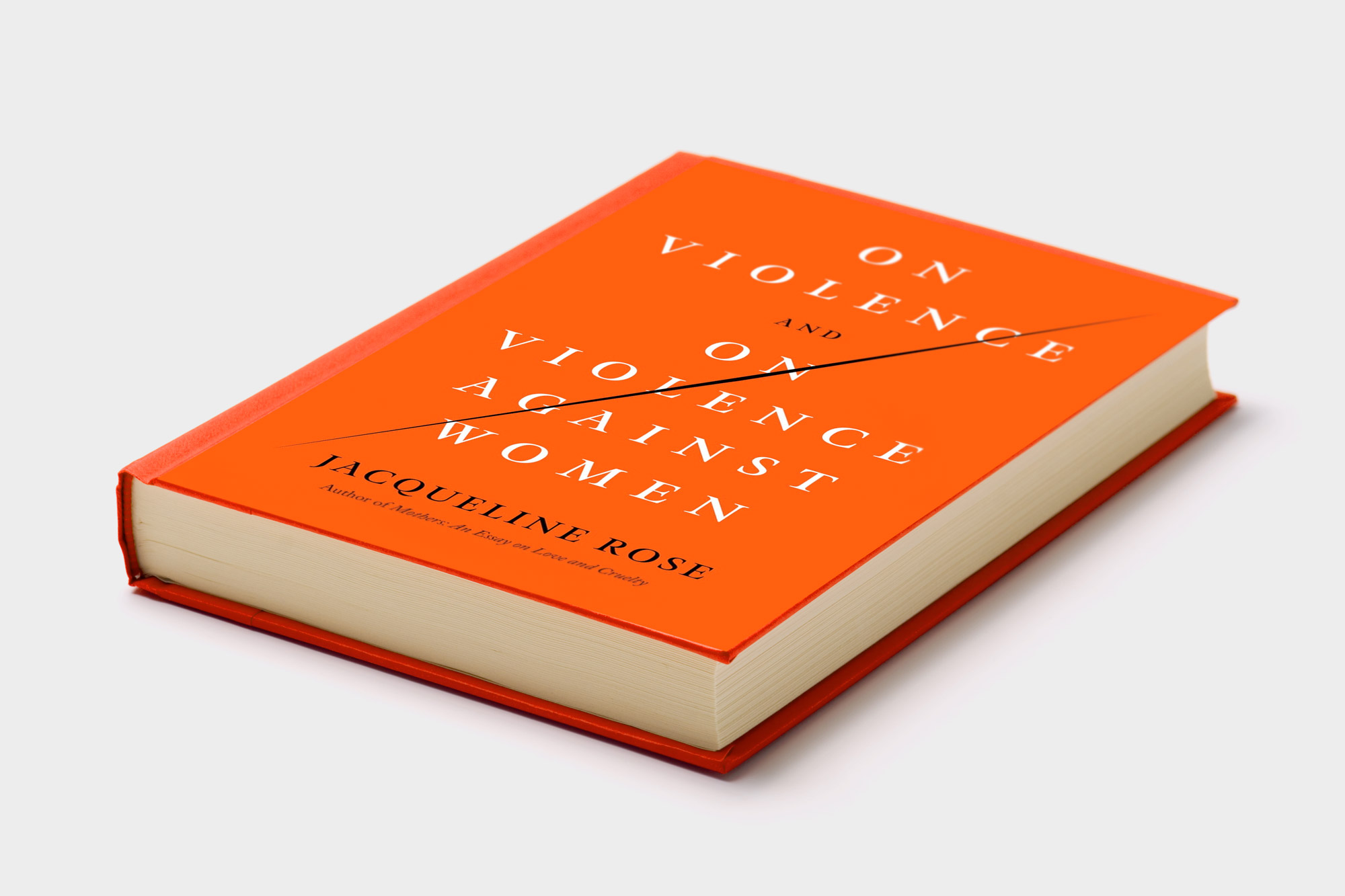

Jacqueline Rose’s new book shows how insecure, fraudulent and counterfeit masculinity is and, along with work by other scholars, contemplates futures free of male violence.

Author:

28 February 2022

In Jacqueline Rose’s latest book, On Violence and On Violence Against Women (Macmillian, 2021), South Africa is an obvious and urgent site. This is not only because it has “one of the worst rates of sexual violence across the world”. The country also makes manifest the continuities between different forms of violence – political; intimate; those that are highly visible; those that exist in the shadows; and those that are seemingly past but feel very much of the present. South Africa is marked by histories of violence and of violence “to come”– captured in the anticipatory hashtag, #AmINext, that became the more popular online slogan here (unlike #MeToo).

For Rose, South Africa presents an exemplary tryst with a legacy of violence that forever haunts the present. You cannot simply get over the past. These hauntings are best uncovered by psychoanalysis, which plays an equal role in the personal and politics: “Political and psychic struggle can be one and the same.”

Indeed, South African academics and activists are precisely in such a moment of deep reckoning with the past. The immediate postapartheid generation laboured to dismantle the state violence of the past – to declare it is “‘done’ with violence”. In contrast, this next generation of scholars and activists has focused on the stubborn persistence of apartheid’s legacies in the present – “there can be no ‘being done’ with violence”.

The killing of Reeva Steenkamp by Oscar Pistorius and the famous trial that Rose stunningly analysed, first in the London Review of Books, is proof of the long afterlife of the past. That Pistorius’s entire defence hinged on the spectre of the nameless, faceless Black intruder or swart gevaar (Black peril) shows the endurance of a white racist imagination in postapartheid South Africa. White women are key to this imagination. Their protection has long justified excessive violence against Black men, even as they might end up as collateral damage.

Related article:

Only a few weeks before Steenkamp was killed, 17-year-old Anene Booysen, who was Black, was gang raped and murdered, on her way home from a tavern in her hometown. Even as she did not have access to the kinds of middle-class security that women like Steenkamp did, she managed her own safety. She did not return alone at night, relying on a man familiar to her to accompany her home. Yet, her death stands testament to how “elusive safety is for women”, as Pumla Dineo Gqola writes in The Female Fear Factory. Notwithstanding the vast differences between them, Rose notes how Steenkamp spoke out against Booysen’s gruesome death just before she died; an “act of race solidarity and gender empathy”.

No woman is safe from gendered violence, but not all women are equally visible or credible or even grievable as victims. While Western feminists argued for and against the rapability of women, Black and postcolonial feminists worried how other women were rendered unrapable (“Black feminists have long tried to complicate white feminist accounts of rape,” writes Amia Srinivasan in her new book, The Right to Sex). The same racist imagination that constructed white women as inherently rapable – by Black men, above all – also produced Black women as sexually available – to white men, above all – and therefore as impossible to rape.

South Africa’s foremost feminist scholar, Gqola reaches deep into the entangled histories of colonialism, indenture and slavery to show how Black women were historically constructed as hypersexual, accessible to white men, and ultimately, unrapable. Or to put it more chillingly, as she does in Rape: A South African Nightmare, “Black women are safe to rape, [raping] them does not count as harm and is therefore permissible”. Feminist scholars like her – and Gabeba Baderoon – appear to have long anticipated Rose’s call to uncover and interrogate histories of rape in South Africa, as opposed to treating gendered violence as a contemporary phenomenon.

They reach for histories older than apartheid – slavocratic and colonial – and more transnational in scope and impact. They show how slavery and colonialism created conditions in which Black women were most likely to be raped, but also least likely to be credible complainants of rape and violence.

An inadequate archive

The historical archive on African women’s experiences of rape, whether under slavery or after, is slim. Pamela Scully provides evidence of the institutionalisation of the rape of Black women in the British-ruled Cape Colony, including an instance of a judge reducing the sentence of a man on learning that the victim was a “bastard coloured” – a case mentioned by Rose, Srinivasan and Gqola. Under apartheid, these institutionalised patterns were sedimented: “No white men were hanged for rape and the only Black men who were hanged for rape were convicted of raping white women.”

It is because of the combined weight of these histories that men “rape women longest burdened with assumptions of unrapability”, Gqola shows in Rape. This includes high-profile men within and outside South Africa. The former president Jacob Zuma was acquitted of rape charges brought forth by Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo (“Khwezi”) precisely because she was framed, in law and public opinion, as being impossible to rape.

Related article:

Gqola equally shows, in her latest book, The Female Fear Factory, how A-list actors Lupita Nyong’o and Salma Hayek felt burdened by historical myths around Black and Latina sexuality. It is no wonder that Harvey Weinstein went for these women as the easiest to discredit. But what Srinivasan terms, after Angela Davis, “white mythology about Black sexuality” also makes it difficult for Black women to name injuries caused by Black men.

In postapartheid South Africa, feminists have struggled to publicly critique patriarchy, without such conversations becoming contestations about racism and colonialism. In an article, Helen Moffett recalls South African author Sindiwe Magona exclaiming, during the Thabo Mbeki years: “I’m sick of hearing apartheid used as an excuse! There can be no excuse, no justification for this behaviour!” The past seemed to foreclose rather than expand conversations on violence and women.

The past, the future and the present

The 2015 to 2016 student movements, RhodesMustFall and FeesMustFall, also made claims that both turned to the past in rejecting colonial histories and opened the possibility of a new, different future, in demanding free education for all. These activists alerted the nation to the unfinished business of the past. They alerted publics elsewhere, too, and enabled highly visible, even spectacular reckonings with the past (Rose traces the removal of a statue of a slave dealer in Bristol in 2020, to RhodesMustFall).

But the South African Fallists turned to the past not simply to recover the pain and injustice that a previous generation had chosen to repress. In their recovery of past political ideologies – Black Consciousness, Pan Africanism, and the evocation of Azania – the students reopened the past for a future that they felt they ought to have been delivered but out of which they were cheated. Scholar Leigh-Ann Naidoo referred to her fellow student activists as time travellers who were turning to the past to move beyond the impasses of the present, to go back to the future. Feminist, queer and trans activists, in particular, materialised a different Azania – one free of patriarchy and male violence.

Related article:

Rose notes contestations around gender within these movements as evidence of how political struggle is always informed by the politics of gender and sexuality. While trends of silencing and normalising sexism were observable in historic Black Consciousness movements, what was unique to this moment was the emergence of a robust feminist challenge to patriarchy. So robust was this challenge that it has been credited with reigniting a new wave of feminist protest on South African campuses that anticipated the tactics and claims of the global #MeToo movement by at least a year.

In their critiques of patriarchy and transphobia in movement spaces, the Trans Collective at the University of Cape Town, for instance, claimed that there will be no Azania if Black men simply fall into the throne of the white man without any comprehensive reorganisation of power.

It matters that these were Black queer and trans students who were naming limits to Black solidarity, and calling out patriarchal violence. Last year alone, between February and October, more than 20 LGBTQIA+ South Africans were murdered. “Transexuals of colour comprise by far the largest number of victims [of murder],” writes Rose.

Technologies of violence

Sexual violence is a powerful technology of gender. It feminises its victims, and masculinises its (mainly male) perpetrators. The phenomenon of the corrective rape of lesbians in postapartheid South Africa exemplifies this logic. Gqola is emphatic that the Female Fear Factory is not just about women, but all “who have been ideologically constructed as female”. This includes gay men who are objects of the kind of violence reserved for women, because their homosexuality renders them woman-like.

For Rose, male violence ultimately reveals how insecure, fraudulent and counterfeit masculinity is – how it operates as what Hannah Arendt would call “impotent bigness”. As opposed to the gender essentialism of radical feminists such as Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin, which is resurgent today, Rose does not accept violence as a natural extension of masculinity. In questioning what it means to be a “real” man or a woman, it is the trans experience that explodes the stability of gender categories in ways that should be welcomed by all feminists, she argues.

Gqola too turns to histories of rape as a way of moving beyond rooting violence in male essence. At the 2021 Edinburgh International Book Festival, which featured both authors, Gqola called patriarchy an anxiety-laden but brutal system, which needed constant and careful feminist vigilance. She was responding to Rose’s hunch that she, Gqola, treated patriarchy as real and not as fake.

The students I encounter at the University of the Witwatersrand are deeply invested in the stability, and indeed, realness of patriarchy. After all, male violence and the fear it incites determines a great deal of their lives, besides their actual life chances. This reality was brutally brought home when a local post office worker raped and murdered Cape Town student Uyinene Mrwetyana.

Related article:

Popular hashtags like #MenAreTrash make it clear where responsibility lies. They also mark a shift in public debate and consciousness. Younger Black women, in particular, feel emboldened to publicly denounce Black men, without worrying about accusations of racism. But notwithstanding the affective, cathartic charge of these slogans, they have their limits.

In holding individual men responsible, public discourse lets off the hook a government that still exhibits little political will in ending the shadow pandemic. #MenAreTrash also offers little room to think of masculinity as anything other than toxic. And debates on gendered violence, whether by governments or ordinary citizens, tend to centre the cis-woman as the default object of violence. They erase the specificity of trans and non-binary experiences of violence and their contributions to shifting public consciousness in ways that have made these conversations possible.

Again, South Africa’s racial past might offer a way forward. In thinking through friendship as a framework of reconciliation in postapartheid South Africa, Sisonke Msimang holds onto a productive tension which insists on both the possibility and impossibility of Black and white South Africans being friends.

Related podcast:

On the one hand, she says that Black people must feel no sense of obligation to be friends across racial lines because this overshadows the more urgent need for Black dignity. On the other hand, she stresses the need to keep alive the possibility of interracial friendship, “because this is the basis upon which a genuine and robust culture of respect in contemporary South Africa will be built”.

The RhodesMustFall Trans Collective appears to be straddling the same contradiction when they write: “Our intervention is an act of Black love. It is a commitment towards making RhodesMustFall the fallist space of our dreams.” Their critique against male violence and patriarchy was directed not only at what is, but what also could be, or the future as a locus of possibility. That this future is rooted in the complexities of love, like friendship, may gesture towards keeping open the gap between forms of violent masculinity and what Rose calls, “the infinite complexity of the human mind”.

South Africa shows the dangers, as Rose insists, of repressing past wounds that return to haunt us. But a new generation of activists and scholars in the country are also deeply committed to futures free of male violence, while broaching the political possibility of love and friendship.