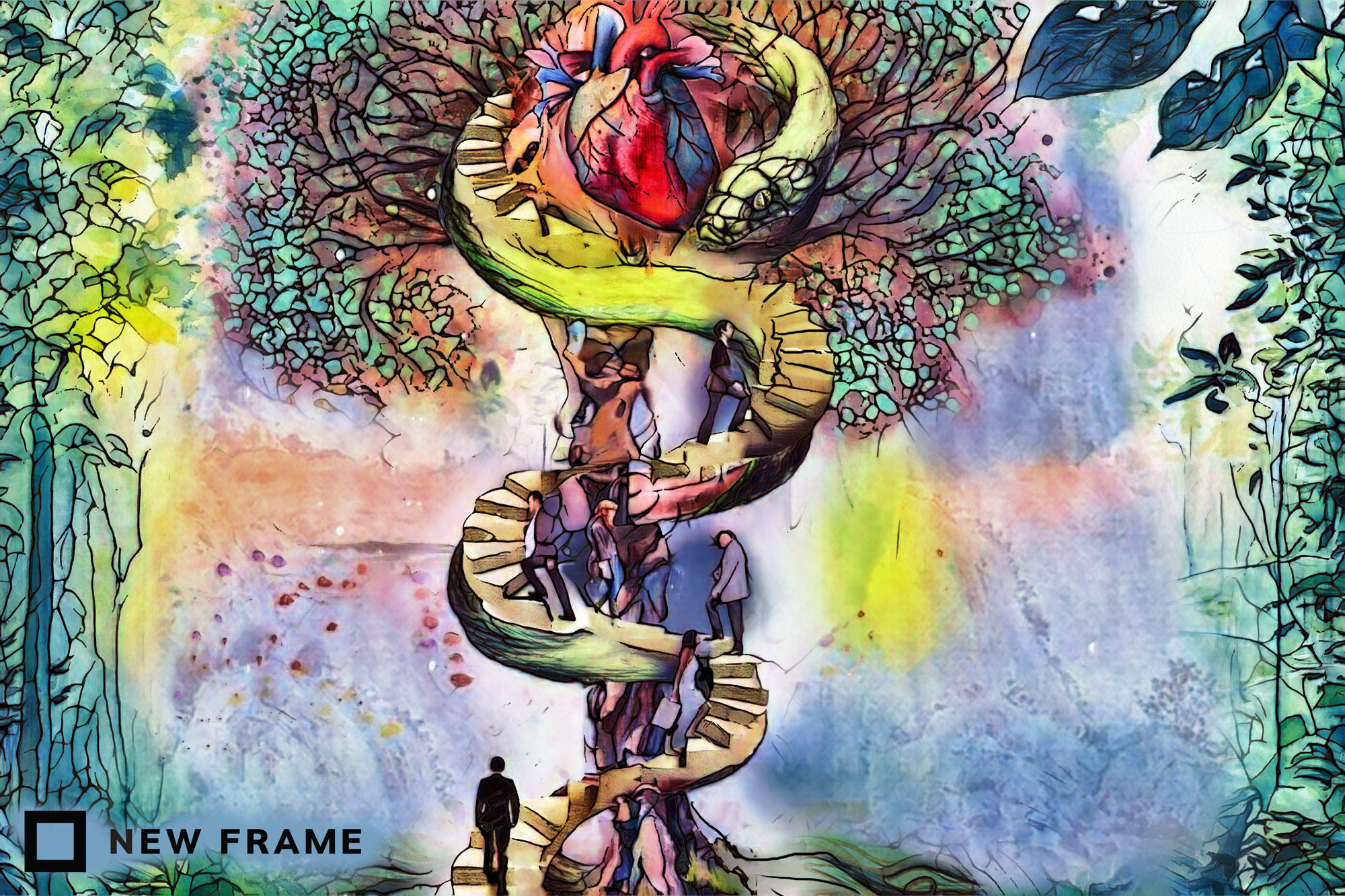

Vaccines are a collective asset for all humankind

Medical science has often been used as a tool of elite power mediated through class, race and gender. But it emerges from shared learning and should be owned in common and used for the public good.

Author:

27 August 2021

As the third and so far most severe wave of the Covid-19 pandemic slowly ebbs, scientists are already advising us to prepare for an imminent fourth wave. With the economy, public healthcare sector and public life already threadbare, this seems tough to accept. As does the likelihood that collective immunity will not be reached and that it will take another year at best before we’re able to return to something resembling life as we knew it.

Even this thin gruel of hope, however, relies on a massive uptake in vaccination. The Scientists Collective advises that around 88% of the population will have to be vaccinated before some semblance of normality returns. It’s a figure that seems to recede endlessly towards the horizon given the low level of vaccination in South Africa, driven by poor government rollout, a flawed public communications strategy and an epidemic of vaccine hesitancy.

Beyond the armchair epidemiology of free-market groups such as Pandemics – Data & Analytics, or Panda, and the perennial scourge of conspiracy theorists, spotted most recently waving anti-5G placards at overworked healthcare workers outside Groote Schuur hospital in Cape Town, one of the notable factors underlying vaccine hesitancy is a fundamental lack of understanding about what a public health crisis actually is.

Related article:

Increasingly, in the age of medical aid and private hospitals, health has come to be seen as a largely personal pursuit. But most of the history of medicine has been social, and has recognised the ways in which the health of each of us is intricately connected to the health of all.

Some form of public health has been with us since the beginning of human civilisations, from Ayurvedic medicine in Southeast Asia to healthy lifestyle promotion in traditional Chinese medicine and social hygiene programmes in the Americas. But it first emerged as an explicit discourse in the mid-1800s, in parts of Europe that were rapidly urbanising and industrialising. This drove impoverished and working-class people into cramped, unhygienic living quarters built around factories and workhouses, and provided the perfect conditions for outbreaks of cholera and the spread of smallpox and other illnesses. It caused a rapid increase in the per capita death rate, which almost doubled in early industrial cities such as Liverpool and Birmingham. And it led to measures like the Vaccination Act of 1853, which introduced compulsory smallpox vaccination.

The contemporary sciences of epidemiology and vaccination, as well as more basic public health interventions such as general hygiene, sanitation, the shifting of slaughterhouses to the periphery of urban areas, nutrition, housing, disease research and the creation of individualised cemeteries, can be traced back to roughly this period. Whereas private medicine is the treatment of individual patients, the public health that emerged in this period was a form of social intervention aimed at protecting and improving the health and wellbeing of communities. When we talk about Covid-19 being a public health crisis, then, the sick patient we’re referring to is society.

Biopower as governance

There is another way to understand the birth of the idea of public health, through what philosopher Michel Foucault calls biopower. He sees biopower as a new form of governance that gained traction in Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries, and which wove its way into colonial projects.

As Foucault observes in his 1974 lecture, The Birth of Social Medicine, the health of individuals and populations, as well as their sexuality and general wellbeing, became linked through new practices to the reproduction of economic and political security. In particular, it made the working class “more fit for labour and less dangerous to the wealthy classes … The appearance of a politics of health must also be related to a much more general process, that which made the ‘wellbeing’ of society one of the essential objectives of political power.”

Related article:

Viewed as an increasing medicalisation of human bodies and behaviours along with the drive for politico-scientific control of the environment as a “public good”, biopower originated in his eyes as a way to maintain a healthy labour force through measures such as mandatory vaccinations, epidemiological data collection, quarantine and so forth. It also served to protect the wealthy from the impoverished as they drew closer together in urban environments.

As Foucault says, among the major objectives of biopower is “the adjustment of a population to an economic apparatus of production and exchange” through a form of “medico-administrative knowledge” that operates on a principle of “making live” and “letting die”.

“Society’s control over individuals was accomplished not only through consciousness or ideology but also in the body and with the body. For capitalist society, it was biopolitics, the biological, the somatic, the corporal, that mattered more than anything else. The body is a biopolitical reality; medicine is a biopolitical strategy.”

A different vocabulary

This view of public health as a form of social control aimed at the regulation of bodies and behaviours should give us pause for thought. Foucault says public health has always been deeply classed, raced and sexed, and that impoverished people have historically been the recipients of medical intervention only to the extent that they have formed an inextricable part of economic life in urban areas. As such, they have often been forced to accept compulsory medical controls. England’s Poor Law, for instance, was in part a form of medical control of the destitute. If he is correct, then perhaps it is not surprising that many feel some residual intuitive discomfort when told that the government and large pharmaceutical corporations have our best interests at heart.

Indeed, it has been easy to see echoes of Foucault’s observation that biopolitical forms of public health are not “the result of a moral necessity, of a global obligation of the rich towards the poor” but “the object of a careful calculation” in the inequality of access to vaccines across the globe, dubbed “vaccine apartheid”. If we have witnessed the historical violation of the bodily autonomy of impoverished and working-class people, of women and colonised people, in the name of public health; if concepts such as immunity have always, Foucault reminds us, been deeply political issues; and if the reach of biopower has been dramatically expanded in the contemporary world through technocratic tools such as big data and artificial intelligence, then should we not balk at participating in top-down medico-political interventions aimed at achieving a “public good” that feels to some like a demand for group consent to economic and political subjugation?

Related article:

But Foucault was not making prescriptive claims. He was simply describing the emergence of specific historical phenomena, and the ways in which knowledge and power came together in new and complex ways as societies changed. A purely negative view of biopower fails to see that similar forms of medical and scientific knowledge could have arisen in different, more egalitarian contexts. And that even within our current society, this knowledge represents the collective labour of all of us, not the property of a small class of political and economic elites.

As urban theorist Benjamin Bratton says, “It is a mistake to reflexively interpret all forms of sensing and modelling as ‘surveillance’ and all forms of active governance as ‘social control’. We need a different and more nuanced vocabulary.”

Our collective right

We should not forget the many struggles by oppressed people to gain access to the technologies that enable public health. The struggle in South Africa for access to life-saving antiretroviral medication for people with HIV and Aids has kept millions alive and in good health. That struggle, waged amid widespread rejection of the science regarding the causes and treatment of the virus, succeeded in placing advanced medical technology in common.

We have to separate our legitimate concerns around the control of bodies for the reproduction of social systems that are not in our collective interests from the great health commons that we have always shared and jointly enriched through our labour – scientific and otherwise – and communal care.

Related article:

Health passports, limited access to public spaces for the unvaccinated and other biopolitical measures could take alarming forms. It is not irrational to fear that these kinds of measures will be used to enforce new forms of border control, xenophobia and national chauvinism. Simultaneously, however, these measures represent the most basic forms of social responsibility available to us. We need to become better at making the distinction between acts of solidarity and biopolitical machinations, as well as the reactionary populism exemplified by conspiracy theorists that has always despised experts and expertise.

In reclaiming our collective right to public health – through small acts of solidarity and by condemning the ways in which the pandemic is being leveraged for economic and political gain – we should remember, as Bratton says, that our “masks are and will be both expressive and functional; they will not only ensure filtration, but also signal our personalities and communicate solidarity with the epidemiological and immunological commons”.

The medical technology that enabled the rapid development of vaccines emerged out of the scientific commons, out of a long history of collective learning with its earliest known origins in ancient Egypt. It must be available in common, for all of humanity. This is also how it needs to be understood and presented, as a collective human asset.