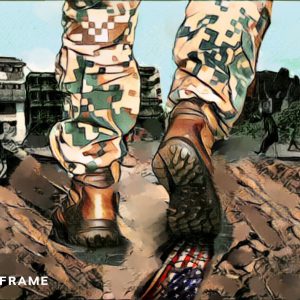

US bases in Africa and the future of African unity

The military presence of the United States in Africa is strategic and enduring. It ensures a fragmented continent, easily pliable to the West’s interests and a convenient site for the ‘new Cold War…

Author:

18 August 2021

This is a lightly edited excerpt from Defending our Sovereignty: US Military Bases in Africa and the Future of African Unity co-published by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and the Socialist Movement of Ghana’s Research Group.

In 1965, Ghana’s former President Kwame Nkrumah published an important book, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, which reflected on the phenomenon of military bases. These had been commonplace during the time of high colonialism, with bases across the continent from the British base at Salisbury in former Rhodesia (present-day Harare, Zimbabwe) to the French base at Mers El Kébir in Algeria. Both the British and the United States militaries had bases in Libya, from the Wheelus Air Base to the military posts in Tobruk and El Adem. In return for the land and the right to barrack troops at these places, the UK and the US provided Libya with “aid”, which Nkrumah rightly said was a payment for the loss of sovereignty. Here is Nkrumah’s assessment of these bases in Africa:

“A world power, having decided on principles of global strategy that it is necessary to have a military base in this or that nominally independent country, must ensure that the country where the base is situated is friendly. Here is another reason for balkanisation. If the base can be situated in a country which is so constituted economically that it cannot survive without substantial ‘aid’ from the military power which owns the base, then, so it is argued, the security of the base can be assured. Like so many of the other assumptions on which neo-colonialism is based, this one is false. The presence of foreign bases arouses popular hostility to the neo-colonial arrangements which permit them more quickly and more surely than does anything else, and throughout Africa these bases are disappearing. Libya may be quoted as an example of how this policy has failed.”

Related article:

In 1964, Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser called for the removal of these bases, and in 1970 – after Colonel Muammar Gaddafi overthrew the monarchy – the bases were removed. Five years before this, Nkrumah correctly judged the mood of the Libyan people. This mood, from 1965, runs through to the present. Since it was set up in 2007, the US government’s Africa Command (Africom) has not been able to find a home on the African continent; the headquarters of Africom is in Stuttgart, Germany. The African people continue to pressure their governments not to give in to US demands to shift the Africom headquarters from Europe to Africa.

Neo-colonialism, Kwame Nkrumah noted, seeks to fragment Africa, weaken African state institutions, prevent African unity and sovereignty, and thereby insert its power to subordinate the aspirations of the continent for pan-African consolidation. Neither the Organisation of African Unity (1963-2002) nor the African Union (2002 onwards) have been able to realise the two most important principles of pan-Africanism: political unity and territorial sovereignty. The enduring presence of foreign military bases not only symbolises the lack of unity and sovereignty; it also equally enforces the fragmentation and subordination of the continent’s peoples and governments.

The surrender of our sovereignty

In 2018, the US Department of Defense proposed that the US and Ghana agree to a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), a $20 million deal that would allow the US military to expand its presence in Ghana. In March, widespread unhappiness at this agreement swept large sections of the population into the streets; opposition parties, who worried about the possibility that the US would build a military base in the country, raised their objections in parliament. By April, Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo said that his government had “not offered a military base, and will not offer a military base to the United States of America”. The US Embassy in Accra repeated this statement, saying that the “United States has not requested, nor does it plan to establish a military base or bases in Ghana”. The SOFA agreement was signed in May 2018.

It does not require a close reading of the agreement’s text to know that there is in fact the possibility that the US could build a base in the country. Article 5, for instance, states, “Ghana hereby provides unimpeded access to and use of agreed facilities and areas to United States forces, United States contractors, and others as mutually agreed. Such agreed facilities and areas, or portions thereof, provided by Ghana shall be designated as either for exclusive use by United States forces or to be jointly used by United States forces and Ghana. Ghana shall also provide access to and use of a runway that meets the requirements of United States forces.”

Through this article, the US is permitted to create its own military facilities in Ghana. By any definition, this means that it can set up a base. The surrender of Ghana’s sovereignty also comes to light where the SOFA agreement states (Article 6) that the US would “be afforded priority in access to and use of agreed facilities and areas” and that said use and access by others “may be authorised with the express consent of both Ghana and United States forces”.

Related article:

Furthermore, Article 3 says that US troops “may possess and carry arms in Ghana while on official duty” and that the US troops shall be accorded “the privileges, exemptions and immunities equivalent to those accorded to the administrative and technical staff of a diplomatic mission”. In other words, the US troops can be armed and, if they are accused of a crime, they will not be tried in Ghana’s courts.

In March 2018, Ghana’s minister of defence, Dominic Nitiwul, was challenged on a radio station by Kwesi Pratt of the Socialist Forum Ghana. Nitiwul said that there was nothing peculiar about this agreement, since other African countries – like Senegal – had signed such agreements. Ghana, said Nitiwul, had signed similar agreements with the US in 1998 and 2007, but these were done in secret because there was no tax waiver. Pratt warned that Ghana would be “surrendering sovereignty” in entering this agreement. The general sentiment in the country was opposed to the base, which is why both the Ghanaian government and the US denied that a base would be built.

Pratt was right. The US presence at Kotoka International Airport in Accra became the heart of the US military’s West Africa Logistics Network. By 2018, weekly flights from Ramstein Air Base in Germany landed in Accra with supplies (including arms and ammunition) for the at least 1 800 US Special Forces troops spread out across West Africa. Brigadier General Leonard Kosinski said in 2019 that this weekly flight was “basically a bus route”. At the Kotoka airport, the US maintains a Cooperative Security Location. This is a base in all but the name.

The US footprint

The African continent does not have an unusually large number of foreign military bases. These can be found across the world, from the US bases in Japan to the British bases in Australia. No country has a greater military footprint around the world than the United States. According to the US National Defense Business Operations Plan (2018-2022), the US military manages a “global portfolio that consists of more than 568 000 assets (buildings and structures), located at nearly 4 800 sites worldwide”. In 2019, Africom produced a list of some of its known military bases on the African continent, distinguished between those with an “enduring footprint” (a permanent base) and those with a “non-enduring footprint” or “lily pads” (a semi-permanent base):

Enduring footprint

1. Chebelley, Djibouti

2. Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti

3. Entebbe, Uganda

4. Mombasa, Kenya

5. Manda Bay, Kenya

6. Libreville, Gabon

7. St Helena, Ascension Island

8. Accra, Ghana

9. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

10. Dakar, Senegal

11. Agadez, Niger

12. Niamey, Niger

13. N’Djamena, Chad

Non-enduring footprint

1. Bizerte, Tunisia

2. Arlit, Niger

3. Dirkou, Niger

4. Diffa, Niger

5. Ouallam, Niger

6. Bamako, Mali

7. Garoua, Cameroon

8. Maroua, Cameroon

9. Misrata, Libya

10. Tripoli, Libya

11. Baledogle, Somalia

12. Bosaso, Somalia

13. Galkayo, Somalia

14. Kismayo, Somalia

15. Mogadishu, Somalia

16. Wajir, Kenya

17. Kotoka, Ghana

The list does not contain the bases where the US uses “host nation facilities”, such as in Singo, Uganda and in Theis, Senegal.

Related article:

The large presence of the US Armed Forces on the African continent is not a surprise. The US has the largest military force on the planet, both in terms of the vast number of resources that the US puts into its military and the reach of the military via its base structure as well as its naval and aerial capacity. No other military force in the world matches that of the United States, which spends more on its military budget than the next eleven countries combined. China, which follows the US in military spending, disburses only a third of what the US spends per year.

The footprint of the US military on the African continent is not only quantitatively larger than that of any other non-African country’s bases on the continent, but the sheer scale of the military’s presence and activities gives it a qualitatively different character; this character includes the capacity of the United States to defend its interests on the continent and to attempt to prevent any serious competition to its control of resources and markets. There are two tasks that the US military fulfils on the continent:

1. Gendarme functions. The US military operates not only to provide an advantage to the United States and its ruling elites, but it functions – along with the armies of the other North Atlantic Treaty Organization (Nato) nations, including France – as the guarantor of Western corporate interests and the principles of capitalism. Nkrumah came to the same conclusion in 1965, stating that “Africa’s raw materials are an important consideration in the military build-up of the Nato countries … Their industries, especially the strategic and nuclear factories, depend largely upon the primary materials that come from the less developed countries”. Reports from the US military routinely sketch out the responsibility of its range of armed forces to ensure a steady stream of raw materials for corporations – especially energy – and to maintain unimpeded movement of goods through shipping channels. Such reports include National Energy Policy (May 2001) from the National Energy Policy Development Group, led by former vice president Dick Cheney, and Assessing and Strengthening the Manufacturing and Defense Industrial Base and Supply Chain Resiliency of the United States (September 2018) from the Interagency Task Force in Fulfilment of Executive Order 13806. In this sense, the US military – alongside its Nato partners – operates as the gendarme not for the world community, but for the beneficiaries of capitalism. Alongside the US is France, whose military presence in Niger is closely linked to the imperatives of the French energy sector, which requires the uranium mined in Arlit (Niger). One in three French light bulbs are powered by the uranium from this town in Niger, which is garrisoned by French troops.

2. The new Cold War. As Chinese private and public commercial interests have increased on the African continent, and as Chinese firms have consistently outbid Western firms, US pressure to contain China on the continent has increased. The US government’s New Africa Strategy (2019) characterised the situation in competitive terms: “Great power competitors, namely China and Russia, are rapidly expanding their financial and political influence across Africa. They are deliberately and aggressively targeting their investments in the region to gain a competitive advantage over the United States.” The European Union followed with a report called Towards a Comprehensive Strategy with Africa (2020), which – while it did not directly mention China – worried about “competition for natural resources”.

Related article:

Rather than develop its own humane commercial and development aid policy that would benefit the African people, the United States has opened up a “new Cold War” against China on the African continent. The development of Africom in 2007 alongside the escalation of US and allied foreign military bases in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and elsewhere are part of this new Cold War.