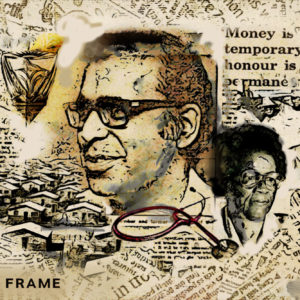

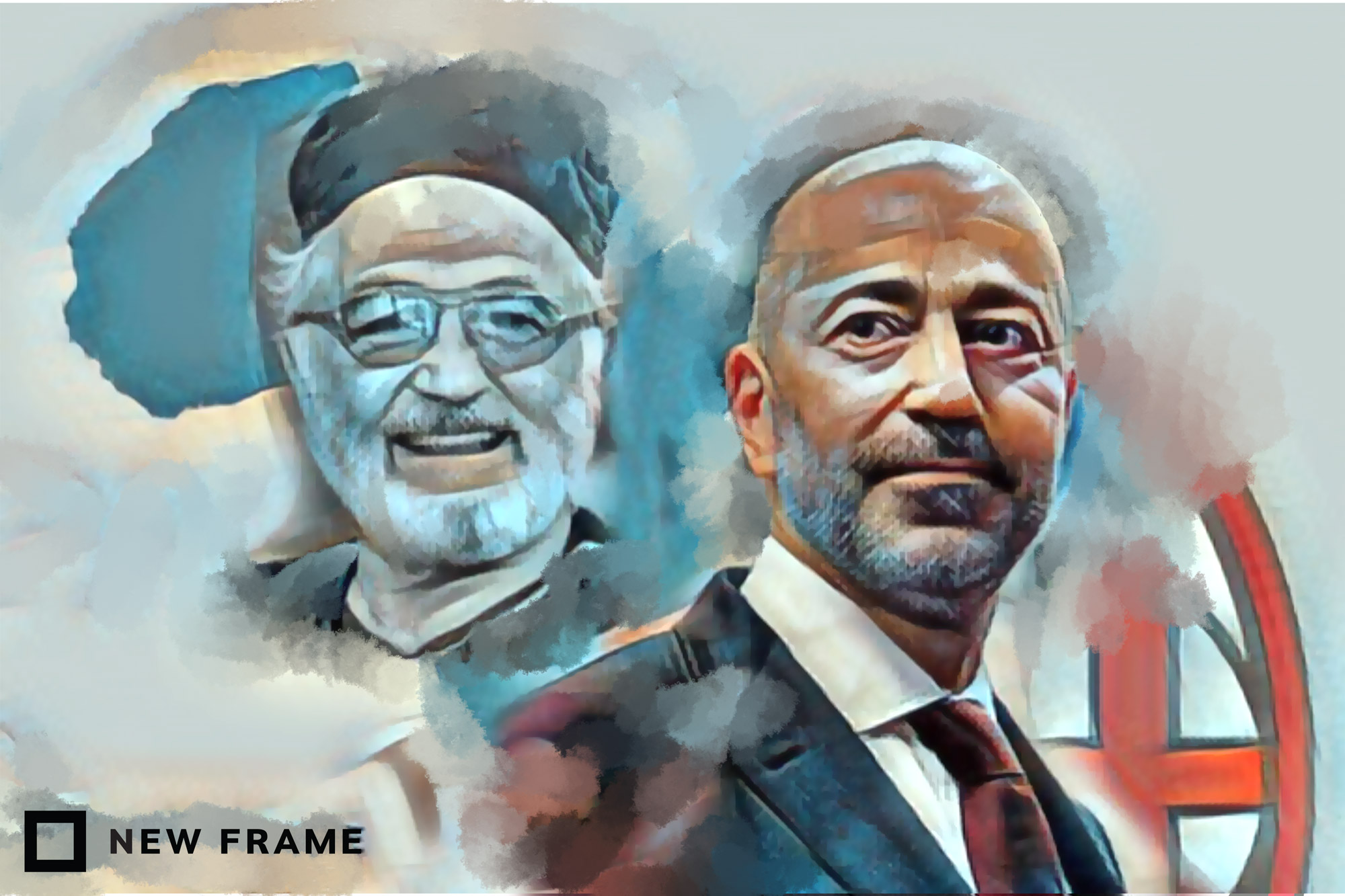

Unlike father, unlike son: Costa and Ivan Gazidis

Former Arsenal football executive Ivan Gazidis was born in South Africa, where his father Costa’s anti-apartheid activities forced the family to the UK, which nurtured Ivan’s abilities.

Author:

3 December 2021

Ivan Gazidis rose to prominence as the chief executive of Arsenal (2009-2018) and AC Milan (2018-present). He might never have risen to these lofty heights had he not moved to the United Kingdom at age four with his anti-apartheid activist father in 1968.

It was in England that Gazidis fell in love with football. It was in that country’s University of Oxford that he obtained the sort of education that would make him the highly regarded administrator he is today.

Gazidis’ father, despite risking his and his family’s lives fighting apartheid in the 1960s, is not well known. Who is he?

Ivan’s father Constantinos Gazidis (later known as Costa Gazi) was a prominent anti-apartheid activist. And his activism, his fight for justice, did not stop with the end of apartheid in 1994.

In the new dispensation, he also stood up to the ANC government’s policy on HIV and Aids – a policy that led to the needless death of many people. He fought these issues as the national health secretary of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC), at a time when it was rare to have a white member climb to such a prominent position in a predominantly Black organisation.

After graduating from Krugersdorp High School, Gazi studied engineering before switching to medicine.

Related article:

A University of the Witwatersrand document on the school’s 1960 medical graduates authored by Chaim M Rosenberg claims that a defining moment in Gazi’s activism was when he refused to participate in a dissection due to his Black classmates being excluded. It has also been widely reported that his activism was sparked by reading Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ Communist Manifesto.

“When the students used to dissect a cadaver, if it was a Black body, all the students watched. When there was a white body, there would be a sign outside to say ‘Whites only’. One day they had thought the body would be Black and it turned out to be white. They asked all the Black students to leave the room. My father also left the room,” Gazidis once shared.

Rosenberg, who was at university with Gazi, said: “As far as I know, Costa Gazidis and Essop Jassat were the only two people in our medical school class willing to stand against the government and risk their careers in the process. It took a lot of guts and sacrifice to do what Costa did. Most of us lacked that level of commitment.”

In 1962, Gazi joined the South African Communist Party (SACP) just as the police began to use spies to infiltrate activist movements. His cell (the lowest level in the organisation’s structure at that time — what other parties would refer to as a branch) was infiltrated by Gerard Ludi (widely known as Gerald Ludi or secret agent Q018, and most famous for his role as a state witness against Bram Fischer).

The SACP’s Paul Trewhela, who did not hold Ludi in high regard, realised while being interrogated by the police that they had access to information that could only have come from him. “I went through three sessions of standing torture in Local Prison, the first of them probably just about a week after the arrests of our SACP group early on 3 July 1964,” Trewhela said.

After apartheid

Even though Gazi had succeeded in reviving his medical career in the UK, having worked his way up to a senior role, he nevertheless returned to South Africa when it was clear apartheid would fall. In 1990, as a PAC member, he stood as a parliamentary candidate. Although he was unable to secure a seat, he continued to serve the organisation as health secretary.

According to a 1999 IOL article, Gazi changed his surname in the 1990s because it was “difficult for people to remember”. The same article stated that he was stabbed by a young PAC ideologue in 1995. “It was purely a racist attack. He did this because I was white. I did not want him charged though, because I thought it would give the PAC bad publicity,” Gazi said then.

On being a member of the PAC even during the struggle years when they were prone to anti-white rhetoric, Gazi said: “The PAC made an impression on me because it had able representatives and a revolutionary orientation. In 1983 the PAC chose me as their ‘Prisoner of the Year’ and I travelled to the United States for a week, addressing the United Nations’ special committee against apartheid.

“People were astonished that the PAC had a white member. I explained the PAC’s position that there is only one race, the human race, unlike the ANC’s multiracialism.”

Related article:

As the PAC’s health secretary, Gazi headed the public health department, a network of 20 community clinics run from Mdantsane’s Cecilia Makiwane hospital. His activism continued as he bravely opposed then health minister Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma’s policy on HIV/Aids.

He landed himself in hot water by accusing her of murder over the government’s refusal to give AZT to HIV-positive pregnant women in 1999. He was fined R1 000 under the Public Service Act for prejudicing the administration of the health department, but this ruling was ultimately overturned.

Gazi’s principled nature and commitment to South Africa were demonstrated on several occasions both long before and after 1994. He is old now and out of the public eye.

Trewhela, who kept contact with Gazi until he moved to Cape Town, said: “His health has been deteriorating for quite a long time. It’s been a good number of years. He’s been helped a lot by his present partner, Janet. I don’t know what condition Costa is in now, I’m afraid.”

The son

Ivan Gazidis was born on 13 September 1964, while his father was in jail serving a sentence that would last until 1967. Six months of his sentence were spent in solitary confinement.

“When I was born, they had told him that I had died, that the birth was not successful,” the AC Milan chief executive was quoted as saying by Front Row Soccer.

Even after his release, Gazi was not allowed to further his studies or be in a room with more than two people at a time. In 1968, he and his family surrendered their South African passports and moved to the United Kingdom, living in council estates in Edinburgh and Portsmouth. He and Dorothea Gazidis, his then wife, divorced and she moved to Manchester with young Ivan.

Unlike his father, Gazidis never returned to South Africa. Having moved to England as a child, he completely assimilated and, like many boys his age, developed a love of football, initially supporting Manchester City. After finishing at Manchester Grammar School, he studied law at Oxford, graduating in 1986. In 2001, he became deputy commissioner of the United States football league, Major League Soccer. He had been with the organisation since 1994.

Related article:

On 1 January 2009, he became Arsenal’s chief executive. Gazidis led Arsenal into the post-Arsene Wenger era, hiring Unai Emery as Wenger’s successor before moving to Milan after one month short of a decade at the Gunners.

At the Rossoneri, he has overseen a period of revival. AC Milan has once again become Serie A title challengers under Stefano Pioli. But, unlike his father’s progressive politics, Ivan was at the centre of the ultimate corporate greed in the form of the European Super League, a proposed breakaway competition from Uefa featuring 12 of its top clubs. Ultimately, plans for the league failed after widespread condemnation from football fans forced several clubs involved to retreat.

A challenging year for Gazidis was made far worse by a throat cancer diagnosis. An AC Milan club statement in July said that he was expected to make a full recovery.

Despite his recent challenges, nobody can deny that Gazidis is now a global force in football. His career, soaring still, is far removed from his beginnings in South Africa.