Ukraine, from pea to matchbox

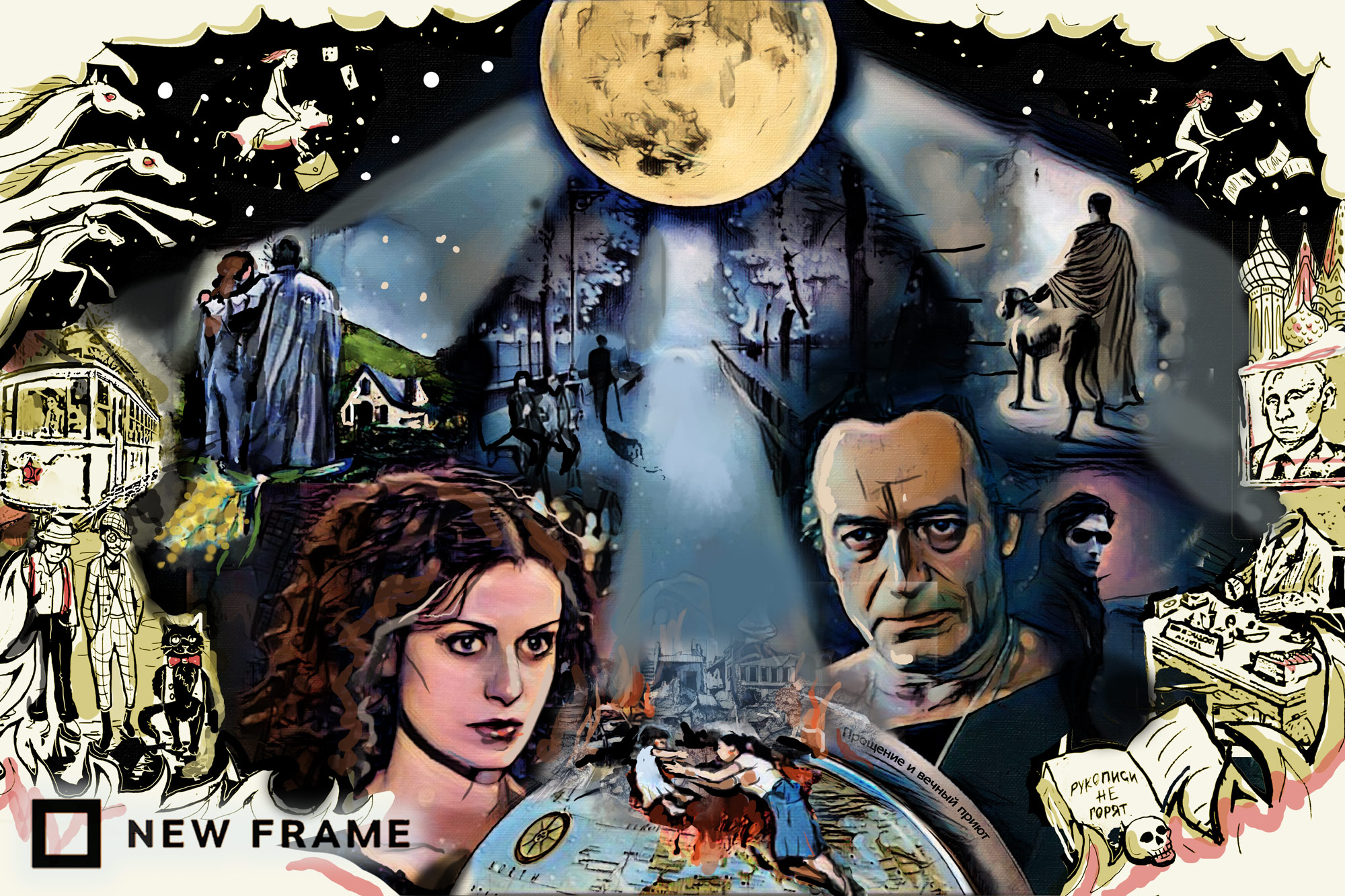

In Text Messages this week, Mikhail Bulgakov proves prescient about Russia’s war in Ukraine in his posthumous 1966 novel The Master and Margarita.

Author:

31 March 2022

Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, has so far avoided the obliteration meted out by the Russian war machine to the seaside city of Mariupol. Kyiv’s tangible culture and history have not been hit or targeted by Russian bombs and missiles and its intangible – poetry, prose, music, song – will survive whatever the result of the invasion.

Among the work that will remain is a literary masterpiece in Russian by Kyiv-born writer Mikhail Bulgakov, who did not live to see his novel The Master and Margarita published. Bulgakov died on 10 March 1940, just short of what would have been his 49th birthday on 3 May. His subversive, satirical and audaciously brave novel was published only in November 1966, and in part-form. The November issue of Moskva magazine carried part one of the manuscript and, within hours, its entire print run of 150 000 sold out.

This ferociously funny deconstruction of Soviet society, corruption and the literary establishment intertwines with a retelling of the meeting between Yeshua Ha-Nozri (Christ) and Pontius Pilate and the former’s subsequent crucifixion. In a land ruled by the Terror of Stalin, where religion was outlawed and “disappeared”, Bulgakov dared to write a manuscript that would have seen him “permanently removed” from society. It was unpublishable, and so much so that Bulgakov burnt early drafts in a fit of fear.

Related podcast:

But from the ashes rose a new manuscript, prompting one of the most-quoted lines from the novel: “Manuscripts don’t burn.” Bulgakov conquered fear and finished his great work, always wary of the state censors who hounded him out of every small theatre job he was allowed to hold, including one to which Stalin himself had appointed the writer. Bulgakov had a frighteningly ambivalent relationship with Stalin, who personally read drafts of his work, intervened a few times to help the writer with authorities and is supposed to have said that a writer of Bulgakov’s quality was above “party words” like “left” and “right”.

Whether that was ever uttered, in The Master and Margarita Bulgakov flies in the face of the political, social and religious strictures of the time, using the satirist’s arsenal of irony, wit, ridicule, parody and caricature to create the most acerbic, sardonic and irreverent burlesque of literary life and lampooning of Soviet governance. Bound up with that is the profoundly spiritual tale of Yeshua – anathema, treachery and heresy to state communism – and a mix of the folkloric and the Rabelaisian in the story-strand of Monsieur Woland (Satan, and Stalin too) and his malevolent assistants Koroviev and Behemoth, a giant cat. There is tenderness and beauty too, in the story of the Master and Margarita.

A ribbon of river

Richard Pevear, in the introduction to his translation with Larissa Volokhonsky of the novel, notes:

“Clearly, what first spurred Bulgakov to write the novel was his outrage at the portrayals of Christ in Soviet anti-religious propaganda (The Godless was an actual monthly magazine of atheism, published from 1922 to 1940). His response was based on a simple reversal – a vivid circumstantial narrative of what was thought to be a ‘myth’ invented by the ruling class, and a breaking down of the self-evident reality of Moscow life by the intrusion of the ‘stranger’.”

Those strangers are the “foreign professor” (Woland/Satan/Stalin), Koroviev and Behemoth, who create havoc in the literary and theatrical worlds of Moscow. Koroviev is tall and thin, dressed in a checked jacket and jockey’s cap, and wears half-broken pince-nez. Behemoth is a tom as large as a pig, black as a rook, with abundant cavalry officer’s whiskers, who walks on his hind legs, drinks champagne, eats caviar with a fork, and when boarding a trolley bus offers to pay the fare of 10 kopecks.

Related article:

The foreign professor claims also to have been at the interrogation and sentencing of Yeshua by Pilate, providing forensic detail of that and the execution which followed, together with vivid descriptions of Jerusalem of the time. Woland is also prescient, in a way that Bulgakov proves to be about the war in Ukraine. Here is Woland talking to Margarita, from the Pevear and Volokhonsky translation:

“For instance, do you see this chunk of land, washed on one side by the ocean? Look, it’s filling with fire. A war has started there. If you look closer, you’ll see the details.” Margarita leaned towards the globe and saw the little square of land spread out, get painted in many colours, and turn as it were into a relief map. And then she saw the little ribbon of a river, and some village near it. A little house the size of a pea grew and became the size of a matchbox. Suddenly and noiselessly the roof of this house flew up along with a cloud of black smoke, and the walls collapsed, so that nothing was left of the little two-storey box except a small heap with black smoke pouring from it. Bringing her eye still closer, Margarita made out a small female figure lying on the ground, and next to her, in a pool of blood, a little child with outstretched arms. “That’s it,” Woland said, smiling…

Today, The Master and Margarita can be read also as a jeremiad of Vladimir Putin’s post-Soviet Russia. Great literature is undying and will always survive the bombs and bullets of outrageous invasion.