Two perpetrators, two ways to face up to complicity

Joao Rodrigues and Paul Erasmus both worked for the apartheid regime and died this year. But while Rodrigues was litigious and tight-lipped, Erasmus tried to help victims’ families.

Author:

17 September 2021

Two very different former members of the apartheid Security Branch died recently.

Joao Rodrigues’ death represents the end of an almost five-decade search by the family of murdered activist Ahmed Timol for answers to what happened to him in John Vorster Square police station on 27 October 1971. Rodrigues was the last surviving member of the security police who, according to his version of events, was in the room with Timol before his death.

Rodrigues died on 6 September, aged 82, in the middle of a three-year legal battle against charges laid against him for his involvement in Timol’s murder and the security police’s subsequent cover-up. He made 19 court appearances to appeal the charges, taking his case unsuccessfully to the Supreme Court of Appeal and the Constitutional Court. The judgment on the merits of his case was pending at the time of his death. This lawfare campaign is estimated to have cost South African taxpayers well over R3 million.

Related article:

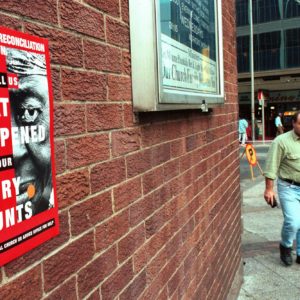

Paul Erasmus’ death was not marked by many reports in the media, but perhaps it should have been. He spent the better part of the past 27 years trying to atone for his role in the apartheid regime by offering what help he could to victims’ families. He gave important information about the workings and practices of the security police to the Goldstone Commission in 1994 and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1998. He also testified at the reopened inquests in 2017 into Timol’s death and in 2020 into Neil Aggett’s death.

Erasmus died at his home in George on 14 July, aged 65. In closing arguments submitted on behalf of Aggett’s family, advocate Howard Varney paid tribute to Erasmus as “one of the few white [Security Branch] officers who acknowledged the harm and pain he had caused to South Africa. He suffered retribution and physical attack because of his disclosures, but this did not stop him from testifying in both the … Timol and … Aggett inquests.”

Rodrigues and Erasmus had never met. They worked in different capacities for the Security Branch at different times, but both were storytellers. It was the kinds of stories they told and the purposes these stories served that set them apart, offering divergent models of how perpetrators can approach questions of justice and reconciliation.

Working for the regime

After leaving the security police in 1973, where he served as an administrative clerk, Rodrigues worked as a journalist for Pretoria newspaper Die Hoofstad, had a subsequent job at South African National Parks and then wrote children’s books. He told no one what he did while he was a police officer. Later it emerged that he had raped his daughter when she was a child. This led her to turn details of his whereabouts over to the Timol family during their recent investigations.

When called on to appear before the reopened inquest into Timol’s death, Rodrigues stuck to the increasingly implausible version of events he had given at the original inquest in 1972. It was his refusal to acknowledge the improbabilities of this version in the face of forensic evidence that led Judge Billy Mothle to recommend that Rodrigues be charged for perjury and as an accessory to Timol’s murder.

This recommendation led to a series of court appearances and judgments that pointed the finger at former members of Thabo Mbeki’s government. It was argued that by virtue of their continued acts of political interference into the prosecution of TRC cases, these politicians were responsible for the decades-long delay in holding Rodrigues and other perpetrators accountable for their crimes.

Rodrigues’ death has served as an indictment of the postapartheid ANC government for its failure to fulfil the promises made to the families of the victims of apartheid-era murderers.

Related article:

Erasmus told his story many times to local and international reporters and was at the time of his death in the process of finalising his memoir, soon to be published by Jacana.

He was a cunning and talented propagandist for the apartheid government, working for the security forces’ Strategic Communications (Stratcom) division, where he became an expert in using a “30% truth to 70% misinformation” ratio to spread disinformation about anti-apartheid activists.

He liked to tell the story of how his superiors assigned him to monitor the seditious performances of musician Roger Lucey in the 1980s. He found himself entranced by the singer’s music and lyrics, eventually becoming one of his most ardent supporters and friends.

Related article:

He also liked to regale reporters with the story of his strange and improbable friendship with Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, whom he asserted had been the victim of a Stratcom operation to implicate her in the activities of the Mandela United Football Club and the murder of child activist Stompie Seipei. The Mother of the Nation acknowledged his loyalty in 1999 by giving her engagement ring from Nelson Mandela to Erasmus’ 13-year-old daughter.

Erasmus kept all his notebooks from his time in the Security Branch and offered them as exhibits whenever he testified. They proved that contrary to the claims of many perpetrators, torture was not only a standard practice but also taught to recruits. Other perpetrators have dismissed Erasmus’ claims as the lies of a renegade security police officer who was motivated by self-interest and anger at his failure to be promoted within the branch. But none ever offered evidence to repudiate him. Erasmus was also not afraid to call out his superiors in the highest levels of the apartheid government for officially sanctioning the actions of the security forces.

Ways to live and die

Rodrigues’ death may yet offer a sliver of hope to the families of apartheid victims. His Constitutional Court appeal might still be heard. This could provide a chance for the highest court in the land to make a ruling on the matter of political interference in TRC prosecutions. This would have implications for those accused of engineering this interference and for perpetrators who may be considering a similar lawfare tactic in the event they are prosecuted for their crimes.

Timol’s nephew Imtiaz Cajee has, for more than 20 years, sought justice for his uncle. He feels Rodrigues should not have been allowed to take his secrets to the grave. “We have to go back to the TRC and ask why Rodrigues was not subpoenaed to testify at the TRC,” Cajee says. “He was living and he was interviewed by TRC investigators. If he had appeared at that time then those other security policemen who were responsible for my uncle’s death and who were alive at the time would have had to come forward.”

Former TRC investigator Piers Pigou, who interviewed Rodrigues as part of the commission’s investigation in 1998, recalls, “I contacted him and initially he was quite open and accommodating and appeared to me to at least want to have a conversation about what the TRC wanted to do. Then when I went to see him in Pretoria, his attitude had changed … He basically put a tape recorder on the table and said, ‘I’m recording this. I’m not interested in coming to the TRC or talking to you without my lawyer present.’ The distinct impression I had was that someone had got to him and he’d been told to shut down. That I think is in character with how he behaved throughout. He’s been a fairly weak individual who’s been given instructions and is following orders from his seniors.”

Pigou says he recommended to the TRC that Rodrigues be subpoenaed to testify but that “never happened”. He says Rodrigues’ subsequent behaviour during the reopened inquest and beyond “was very much in character [for] a man who was intent on not assisting with the process of truth recovery. This for me is the key distinction with Erasmus. Erasmus was bending over backwards to help in whatever way he could. Perhaps he was sometimes overly keen to do it in some respects but I think there was a genuine attempt by Erasmus to be really candid.”

Related article:

Foundation for Human Rights director and former TRC commissioner Yasmin Sooka echoes this assessment of the differences between the men. She says Rodrigues was “in many ways an unrepentant paedophile and apartheid criminal who certainly didn’t see the light and was intent on using every possible legal weapon he had to escape from ever having to incriminate himself or tell the truth”. Sooka says her opinion of Rodrigues “is coloured by the fact that he molested his daughter”.

“When you look at that kind of personality, I’m not really surprised that he wasn’t willing to tell the truth. I’ve dealt with many perpetrators and you see those who are pathological liars and I think Rodrigues fell into that category – unrepentant, pathological, never going to come clean.”

Sooka says Erasmus “had a huge conversion of faith, already when he was a witness for the Goldstone Commission. When you read his book you get a sense of a man who was really wrestling with all of these issues. He wasn’t necessarily a bad man, he was just in a bad space and time. You make choices, and he certainly made the right choices at a time when it was still risky to do so.”

Related article:

Rodrigues did offer some closure to his daughter Tilana Stander when he admitted to sexually assaulting her as part of a mediation agreement between them in July. An affidavit in court read, “The big judge [God] directed him to make right … the indescribable mess he had made.” Stander accepted the apology but made it clear that there was no possibility of a reconciliation. If Rodrigues had been as willing to make a similar gesture in Timol’s case, Cajee says, “if he had met me halfway and said, ‘Look, this is what transpired,’ an honest, remorseful confession would have led me to support a plea bargain option he put on the table. He had the answers.”

There are many ways to die – Rodrigues died at his home in Pretoria, after having been discharged from hospital, with the truth still hidden. Erasmus died at his home in George, after an unsuccessful attempt to obtain a kidney for a transplant, with his stories told. Pigou says Erasmus “probably [died] with a sense of peace that Rodrigues never had”.

There are many ways to live – particularly for those who live in the shadow of their transgressions. Erasmus demonstrated how best to live with oneself and others when one has made terrible mistakes while Rodrigues lived a self-serving lie he maintained by any means.