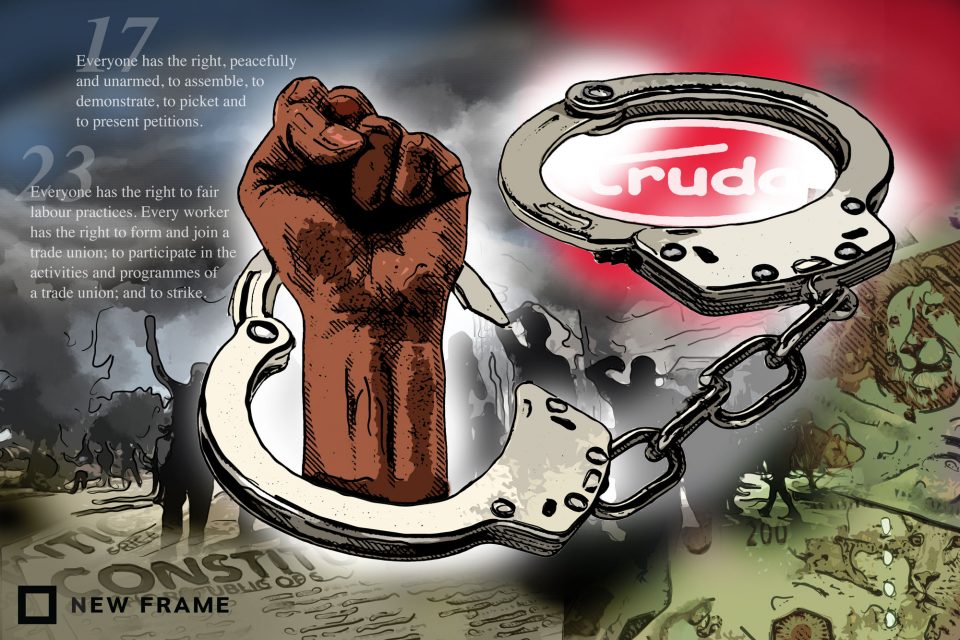

Truda forces protesters into court

In this third part of our story on a strike at an Eastern Cape factory, the food giant’s application for contempt of an interim interdict includes a prison sentence request for protest leaders.

Author:

19 November 2020

The Truda Foods company has said that the union and civic organisation leaders it claims have breached a court order should be jailed. The company in Komani, Eastern Cape, says that “short of incarceration, [the respondents] will stop at nothing and will persist with their unlawful conduct in disrupting and preventing [Truda] from carrying out its business operations”, according to court papers.

On 30 October, the labour court in Port Elizabeth summoned the leaders of the Komani Residents Association (Kora), South African Security and Allied Workers Union (Saswu) general secretary Xolile Mashukuca and five worker leaders from Truda Foods to appear in court on 9 December on charges of being in contempt of an interim interdict.

Following a picket, Truda Foods won an interdict on 21 October against the group and more than 70 other employees that bars them from disrupting Truda’s operations and posting untrue or defamatory comments about the company on social media.

Truda’s accusations

In fresh court papers, Truda chief operating officer Stephen Edwards said the group of nine breached the interim interdict by “attacking, intimidating and threatening” Truda employees on three occasions after the order was granted. A contempt of court conviction carries either a R5 000 fine or a 90-day jail term.

Truda cited numerous examples of how it says its interdict has been breached. For example, it complained that when it sent the interim interdict to Kora secretary Thulani Bukani via WhatsApp, he wrote back, “Who is this?”

Kora deputy chairperson Zolile Xalisa replied to the same WhatsApp message with “a photograph of what appears to be guerrillas in military fatigues holding automatic assault rifles” and “a vulgar and contemptuous comment, ‘Fokof’”, said Edwards. Truda says this indicated that Xalisa had no intention of abiding by the terms of the interdict.

Truda included photographs of broken windows at the homes of five of its managers. On 27 October, unknown vandals threw rocks at the houses. Edwards said, “There is no direct evidence linking the respondents to this unlawful conduct. I do, however, strongly suspect that the attack on [Truda] staff members is directly linked to the protest action at its factory.”

PART ONE:

The company also said a Facebook post by Mashukuca was in breach of the interdict. It read: “Ngaphandle [outside] Truda Foods, abasebenzi [workers] are protesting peacefully, no retreat, no surrender.”

Truda included in its court papers photographs of a group of about 100 workers protesting after the interdict was handed down, and said the company was “forced to stop its business operations and lock down its factory for the safety of its staff members”.

But Bukani said organisers went to the protest to inform workers of the terms of the interdict and to get them to move 7km away to Ezibeleni, where employees have protested since.

“Truda Foods is just using their money to threaten everyone who dares question their way of operating, which is suppressive to the workers. This company has no interest in resolving the matter. The interest they have is to bully and silence anyone through courts,” said Bukani.

PART TWO:

Despite Truda asking the labour court judge to incarcerate the union leaders and community activists, when asked if he thought it was fair and reasonable for them to be jailed, Truda Foods chief executive Colin van Heerden said, “We don’t know what’s fair and reasonable – a court will decide. What we do know is that we have a duty to protect our staff, the hundreds of mostly women, from being stoned and beaten because they want to earn some money to feed their children.”

There was no mention in Truda’s court papers of Truda employees or Saswu or Kora leaders stoning or assaulting women. When asked what evidence he had that the protesters hurt women workers and why this was not in the court papers, Van Heerden did not respond.

Truda Foods said workers armed themselves with metal rods, bricks and sticks, but when asked to confirm that the group of nine did this, Van Heerden again did not respond.

Involving the courts

Right to Protest attorney Stanley Malematja, from the Centre for Applied Legal Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand, said applying for a contempt of court order was an attempt by Truda Foods to “rope in the criminal aspects of the law. The aim is to have the interdicted respondents locked up.”

An interdict cannot stop the protests, because the right to free assembly is protected by Section 17 of the Constitution, Malematja added.

“The ‘disturbance’ nature of a protest does not mean that such a protest loses the protection of the Constitution. It is not unusual that during a protest, a factory will have to halt production and attend to the protesting employees so that issues may be resolved. In the event that issues are unresolved, the protest is bound to continue. With financial power but no negotiating skills, an employer would approach the court on an urgent basis to interdict the protesting employees,” Malematja said.

Related article:

The judiciary does not yet recognise such interdicts as strategic litigation against public participation lawsuits, known as Slapp suits. “When issues are raised by a few employees, they may easily be ignored. But when raised by the majority, then the employer is compelled to lend a listening ear. Those who do not want to lend a listening ear normally hide behind Slapp suits and the orders are used as shields to hinder people from seeking accountability through protests. An important question to the employer is, ‘How do you expect your business to run as normal while your employees have grievances?’” said Malematja.

The nine people called to court will have to prove they did not disobey the interdict and engaged “in their constitutional right to free assembly”, Malematja said. “The respondents must satisfy the court that at no point did they intimidate or harass any employee or interfere with the business operations of the applicant. The respondents must make it clear that the protest was not the reason for the closure of the business.”