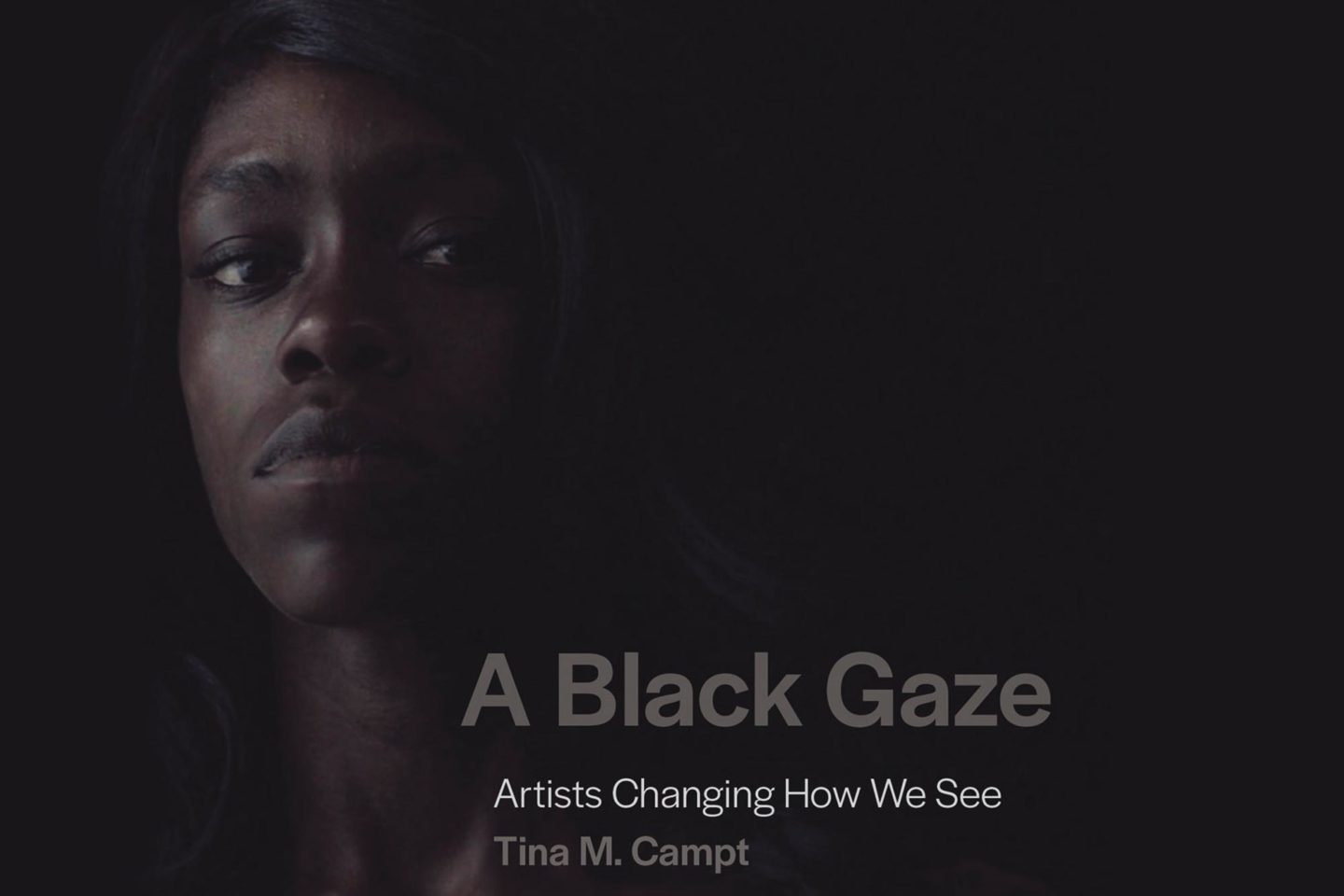

Tina Campt’s radical vision

The cultural criticism scholar argues in A Black Gaze that certain art transforms viewers into witnesses, pushing them into an encounter with themselves as seen through the complexity of blackness.

Author:

28 October 2021

Tina Campt chooses words with care. In talking and writing, she opens them up, asking what they reveal, invite, conceal, imply and make possible. Reading A Black Gaze (MIT Press, 2021), it is clear that she both loves language and questions it.

“I do have a state of great wonder about the power of words to elicit responses and that they can be so precise,” she says. “At the same time, that precision is an opening to a multiplicity of understandings, and that was the joy of writing this book.”

She infuses this kind of sensory sensibility into A Black Gaze, a lyrical academic text that is alive, multidirectional and clear, even while asking readers to work with the tensions inherent in the theory she builds over the book’s seven “verses”.

Campt writes as she speaks, in an imaginative, playful mode that is rapt with joy and, as she says on our Zoom call, filled with “wonder”. This is striking in an academic world so often laden with dense, near opaque texts and elite vocabulary. In Campt’s work, Jacques Lacan sits alongside text riffing on Arthur Jaffa and Jay Z’s 4:44. Illuminating personal anecdotes and a vernacular Black vocabulary make the work conversational and attuned to the way art meets popular culture, the everyday and readers.

In conversation and on the page, she is attentive and warm, listening as much to what is on the surface as to what is layered within. When I ask whether there is space in the academy for accessible language, she catches that “there is sort of a sub-question to what you’re asking, which is, What is the status of accessible language in Black Studies? … I feel like it’s going in two directions – it’s going in the much-more-accessible-language direction, and it’s going in the much-more-opaque direction at the same time.”

In her own writing, Campt is propelled towards clarity, asking herself what she really wants to say, who is her audience and who are the thinkers she is working alongside. “Accessible writing,” she says, “sacrifices density for intensity, and the intensity of the response that you can evoke from somebody by being crystal clear is extraordinary.” Her words echo James Baldwin’s goal to “write a sentence as clean as a bone”.

Campt makes theory by “chipping away and reducing it down, taking layers away … that is, stripping it down to what I see, think, feel and hear”. There has been a radical shift in her writing over the course of her four books, the others being Other Germans: Black Germans and the Politics of Race, Gender and Memory in the Third Reich (2004), Image Matters: Archive, Photography and the African Diaspora in Europe (2012) and Listening to Images (2017) .

Rereading her first book, she thought, “There are too many words here.” She laughs. A Black Gaze, for Campt, is “really theorising while talking and listening”.

The journey of theory-making

As Campt creates concepts in which familiar words such as “flow”, “slowness” or “hum” sit alongside “haptic”, “fabulation” and “the visual frequency of Black life”, they appear with their new and sometimes multiple definitions in the margins. This functions like a glossary, and more – it is an invitation into her world and mind.

Campt takes readers by the hand and walks us through the text, sometimes literally writing, “Let’s go here” or “We now turn to this”. In A Black Gaze, she is not alone, but is accompanied by the artists, art, collaborators, students and the readers with whom she engages, creating a world built for all of us in just over 200 pages.

As a Black feminist theorist and the Owen F Walker professor of Humanities and Modern Culture and Media at Brown University, Campt’s work merges art, popular and visual cultures, creating theory to explain and illuminate the work of Black artists and the everyday creativity of Black people.

Related article:

Structured in verses rather than chapters, A Black Gaze explores the work of eight artists, Arthur Jafa, Simone Leigh, Okwui Okpokwasili, Dawoud Bey, Jenn Nkiru, Deana Lawson, Kahlil Joseph and Luke Willis Thompson. Each engages the multiplicity of Black experiences, possibilities and precarity.

The concept unfolds as the book progresses, with each verse offering connected aspects of what Campt means by “a Black gaze”. The layout reflects the way the ideas arrived for her, accruing over time and emerging as she thought about the demands of certain artworks on viewers, coming to understand that they all held something in common.

A Black Gaze centrally explores how “Black contemporary artists are creating new ways of visualising Black struggle and transcendence, and in doing so, they offer a different trajectory for Black sociality”, or ways of being and of being together. This defies the terms of white supremacy, which locks blackness into a singular way of being and of being seen.

Defining a Black gaze

Today, as Campt writes, we find ourselves in a peculiar paradox. We are inundated with images of precarious Black life and, simultaneously, we are experiencing the “striking ascendancy of Black aesthetics in pop culture and the art world”. A Black Gaze locates itself, speaks from and emerges within this paradox.

The concept is not about Black ways of seeing, “looking at Black people” or what she calls “simply multiplying the representation of Black folks”. It is a theory she uses to explain how certain artists pose a radical question: “What would it mean to see oneself through the complex positionality that is blackness – and work through its implications on and for oneself?”

In this art, Black life is not “rendered in ways that allow it to be engaged at a safe distance or viewed at arm’s length through a lens of pity, sympathy or concern”. Rather, these renditions of Black life shift us, asking us to question how and from where we see.

Related article:

This kind of art illuminates the dynamism of Black life and “cannot be engaged passively”. It requires “effort and exertion”, Campt writes. A Black gaze then “transforms viewers into witnesses and demands a confrontation”, shifting “the optics of ‘looking at’ to a politics of looking with, through and alongside another”. It becomes a critical framework, a reading apparatus, a term to describe a practice and way of exploring how the art she writes about demands “particularly active modes of watching, listening and witnessing”.

Campt is aware that the use of her term “Black gaze” is fraught, and she excavates these challenges in her work, noting how “the gaze” is a loaded term in cultural criticism because it is rooted in oppressive white male power and ways of seeing.

Campt, however, asks us to be open. “I never want to give anything up” to power, she explains. “That is my practice of refusal. I refuse the choices that limit my possibility to express the complexity of Black life, and that’s really important to me.”

Her words echo a critical centre of her thinking. With Saidiya Hartman in 2015 she founded the Practicing Refusal Collective, a Black feminist forum of scholars and thinkers who consider Black life in community and in exciting, distinct and imaginative ways.

In refusal, for Campt, everything is both/and, never either/or. A Black Gaze asks us to think about art that reckons with the dynamics of Black life’s existence on the vast spectrums between pleasure and pain, life and death, freedom and oppression, joy and precarity, danger and dancing – all at once. It also asks us to reckon with any discomfort and difficulty this causes.

At its root, it is a book about the artists she identifies as exemplifying this new way of seeing and witnessing – but it is also about so much more. It grapples with what it means to be Black in the world right now, in all its complexity, distinctions and convergences across geographies and experiences. It is about recognising “that Black life is constituted through vulnerability to the overwhelming force of anti-blackness and white supremacy, and yet not capitulating to only be known by those forces”.

The strength of her work rests in an acute acknowledgement of tensions, contradictions and conflicts in this, all while thinking beyond these limits.

Encountering Campt

In her work, Campt is “drawn to counter-intuitive concepts”, such as the idea of “listening to images”. For her, “counter-intuition requires us to think beyond our comfort zone, to think oppositions in tandem and to think them in a different grammar”. By grammar here, she means the tense she calls “the future real conditional” – to move as though what needs to happen for us to be free has already taken place. This means aspiring to, living, imagining, constructing and practising the possibilities of freedom at once and in the present.

In creating the concepts in A Black Gaze, Campt says, “I don’t want my readers to labour over the content of what I’m trying to say. I want them to labour over the affect of understanding that content. It’s that I will invite you into a place where you may be uncomfortable and you may have to work, but it’s not because the door is too hard to get open, it’s because you got into that room and you looked around and you’re like, shit, this is hard.” Her voice bounces between a knowing empathy and laughter.

Campt’s cultural criticism takes pop culture seriously, and her work exemplifies the best of its kind. It asks us to think deeply about the everyday, and the music, literature and art we constantly encounter. It gestures to and reflects on what they show us about who we are, who we are becoming and who we want to be, speaking across our individual experiences. It allows us to understand how a song, dance, phrase, artwork or music video can contain all the rich tensions of our world.

Across space and position

A Black Gaze demands that we deal with the difficulties that some art produces in us, asking us to think about the vastness of contemporary Black experiences, encouraging us to sit with them and reckon with what they stir up in us. In conversation with Sarah Lewis, Campt explains it as “being able to be accountable to the responses that engaging with the works that position us in relation to the precarity of Black life trigger in us – being responsive to that as opposed to suppressing it”. For Campt these kinds of work have “potentially transformative effects … when we allow ourselves to inhabit those feelings and responses”.

Reading the work from South Africa, one wonders how the theory might travel. Campt invites this, describes the book as “in invitation to reflection” from different perspectives, as we strive to find our way to each other across Black experiences.

Related article:

A Black Gaze gives us perspective and possibilities. This is perhaps best expressed in the cover. Campt explains how in the Jafa image Crystal and Nick Siegfried (2017), “depending on how you’re looking at it, she sort of moves in and out of shadow, and you can and cannot see her in certain perspectives”. That is what she is talking about with A Black Gaze, “a gaze that positions us in relationship to Blackness”. It is not static; it is mobile. “We need to be about to position ourselves and understand what that positioning means, and that includes me,” she says.

Across our dynamic experiences, A Black Gaze is “the rejection of the status quo as livable by creating possibility in the face of negation”. In this moving, productive spirit, Campt closes the book with the words, “Rebirth is necessary”, loaned from the title of a Nkiru work. And in Campt’s world, as in ours, it is radically, beautifully, always possible.