The win-at-all-costs culture of steroid abuse

A new book on drug use in South African sport depicts institutions that will stop at nothing to make money – even encouraging athletes to take banned substances.

Author:

31 March 2022

On her first date with her future husband, the Russian middle-distance runner Yuliya Rusanova confessed that she had been using illegal steroids. She told him that “it’s not like I’m breaking the rules. These are the rules … to be a top athlete; this is what it takes.” Remarkably, she said this to Vitaly Stepanov, who worked for Russia’s anti-doping agency. Rusanova later became an informant, secretly capturing evidence of officials and trainers pushing athletes to use banned performance-enhancing substances.

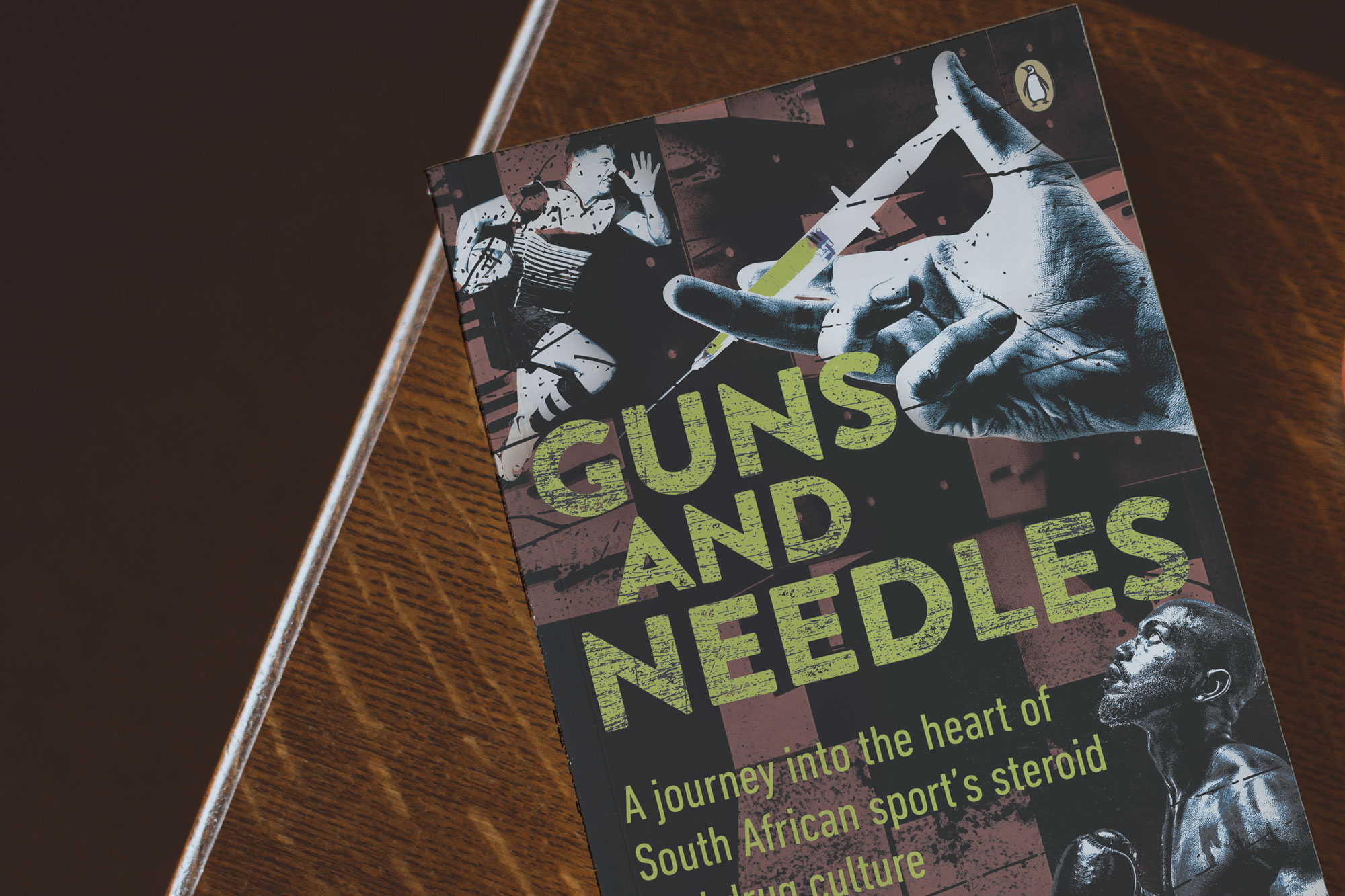

Guns and Needles: A Journey into the Heart of South African Sport’s Steroid and Drug Culture (Penguin, 2022), sports journalist Clinton van der Berg’s new book, explores how the attitude of “this is what it takes” pervades modern athletics and sports. From Mike Tyson’s convoluted schemes to avoid testing positive for cocaine to South African school children ruining promising careers by taking banned “supplements”, the book lifts the lid on the clandestine underbelly of competitive sports. Off the pitch and the racetrack are sordid scenes of needles and blood-soaked tissues from injections discarded on changing room floors as sporting bodies push athletes to take drugs that often cause severe physical and psychological damage.

Related article:

The unregulated world of performance-enhancing drugs also blurs into organised crime. In one case, the Hawks investigation unit raided an illicit lab in East London, where manufacturers were mixing horse steroids with human-oriented products. Despite these unsafe conditions, the supplier had been selling “supplements” to the Makro wholesale chain.

Brian Wainstein, also known as the “steroid king” was murdered at his house in Cape Town in 2017. Born in Israel, Wainstein was a fugitive laying low in South Africa, on the lam for running “the biggest steroid operation in the world”. While in Cape Town, he forced local businesses to buy his steroid brand, allegedly threatening “to blow up their stores” if business owners refused. The subsequent investigation into his murder implicated prominent underworld figures, including crime boss Mark Lifman and gang leader Jerome “Donkie” Booysen.

Widespread steroid use fuels aggression, which is especially dangerous when hitmen and gangsters abuse the substance. As the testimony of one of Booysen’s informants puts it, “You forget your strength … and you don’t realise it, so when you give a guy a klap [smack], you kill him.”

Broken dreams

But Van der Berg does not only indulge in salacious gossip. He writes with both empathy and humour about overweening ambition and thwarted dreams. By providing an unfair advantage through expanding strength and speed achieved without training, steroids go “against the spirit of sport”. Authorities often take a hardline stance with athletes who test positive, not only for steroids but also for recreational drugs such as marijuana, which may be used for personal rather than performance-enhancing reasons. Sportspeople who fail tests may have their careers immediately derailed and are shamed as cheaters. But the often humiliating ritual of testing urine samples is not an exact science.

While there are athletes who go to great lengths to disguise their drug use, there are also many cases of testing procedures creating false positives. In 1992, Charl Mattheus became the first Comrades ultramarathon winner to be stripped of the title after testing positive for a banned substance – but this was from an over-the-counter cold medicine. He was later exonerated. Ludwick Mamabolo, who won the 2012 Comrades, was accused of using the drug methylhexaneamine, before being proven innocent.

But while the media focuses on the illicit practices of individuals, the book reveals it to be a systematic issue. American cyclist Lance Armstrong was a global hero for winning multiple Tour de France races while also surviving testicular cancer. His career collapsed into infamy in 2012 when he was identified as the leader of a doping ring within the US Postal Service racing team, using blood transfusions and monumental quantities of human growth hormones.

Related article:

But this was just one scandal in an event dogged by cheating allegations. As far back as 1923, Tour de France winners boasted that they had “cocaine to go in our eyes, chloroform for our gums and do you want to see the pills? We keep going on dynamite. In the evening we dance around our rooms instead of sleeping.” In 2004, winner Marco Pantani died from acute cocaine poisoning.

Rather than involving individual deviancy, doping receives institutional support. Coaches and sporting bodies have, in many cases, adopted an attitude of “everyone else is doing it, so why can’t we?”, believing that not cheating will put them at a competitive disadvantage.

This provides authorities with plausible deniability, in which they informally encourage athletes to use steroids and stimulants, but disavow them if they are caught. Doping has even taken the form of complex government schemes that involve cooperation and comprehensive planning by high-level officials. During the Cold War, for example, the former East Germany became a formidable Olympics competitor, but its haul of medals was achieved by a state-sanctioned programme of mass drugging of its athletes.

An unethical drive

The dark side of sporting culture reflects the wider values of late capitalism, which prioritises the spectacle of power and the appearance of strength. The “drive to make money”, from both individuals and sporting institutions, “overrides any ethical consideration”.

In his discussion of South African rugby at both the school and professional levels, Van der Berg explores how the sport has become dominated by a focus on winning at all costs, which expects players to be hulking supermen. This creates a distorted sense of perspective within schoolboy rugby, encouraged by pushy parents and ambitious coaches, who press youths into using illicit substances. The book notes several cases of promising athletes from impoverished backgrounds ruining their prospects after being caught. In professional rugby it is no better, with players often washing out by age 30 with severe physical damage. Many of the stars of the 1995 Rugby World Cup, such as Springboks Chester Williams and James Small and All Black Jonah Lomu, died young.

Related article:

A fascinating dive into the hidden politics of sport, Guns and Needles suggests that the problem is not with the desire for personal glory and athletic achievement. Rather, it is how the relentless pressures to make money and achieve fame have twisted a more balanced and healthy approach to sport and competition that should be based on fair play and personal development.