The train vendor who became a professor

When his bursary fell through, Tendayi Sithole found a home among train vendors who opened a way for him to save for university. It led to him becoming an associate professor of African politics.

Author:

31 May 2019

The University of South Africa’s (Unisa) Theo van Wijk building stands on a hill in Tshwane, overlooking the valley where the Gautrain and Metrorail lines converge – two railways marking a million train journeys that have shaped our land.

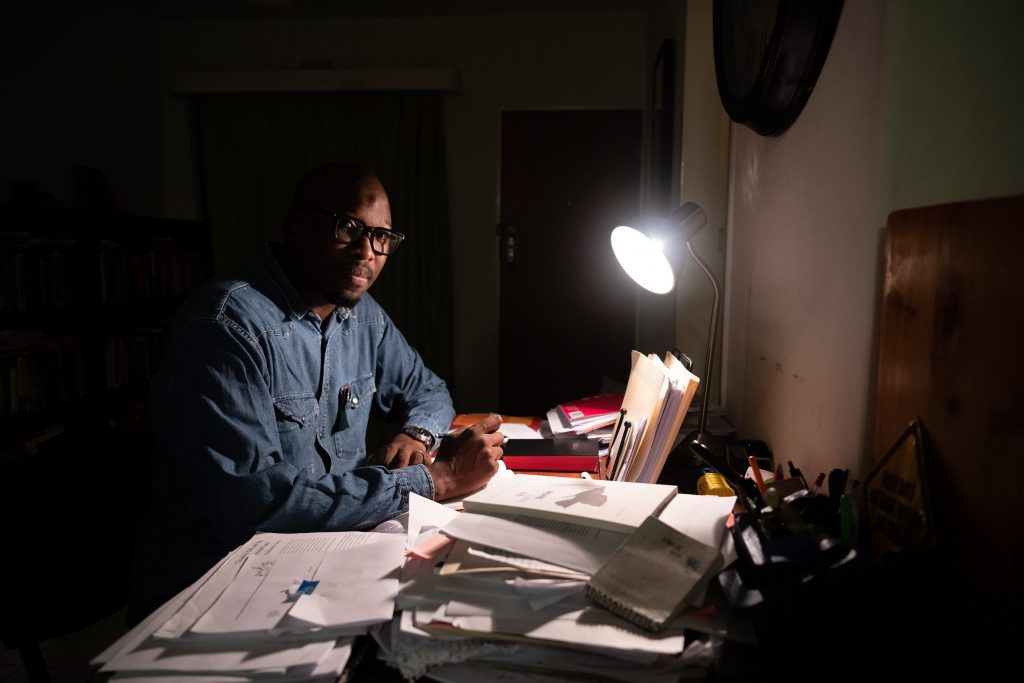

It is here that New Frame spoke to Tendayi Sithole, associate professor of African politics, about his journey, dreams and the plans he hatched during his days as a train vendor.

The train, or stimela, is a central defining feature of working-class life and may well have birthed modernity in the land of the fallen rand. iGailo, as it’s called by users, is more than a mode of transport for commuters. “It’s a social experience on wheels,” says Sithole excitedly.

Much of our national history has its genesis on the railway lines, like the migrant labour system that built our nascent modern economy and body politic.

It was on a train ride to the university currently known as Rhodes in then Grahamstown during the winter of 1967 that anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko and his companions transformed the future of racial politics. They were travelling to a gathering of the National Union of South African Students when they were sold on the idea to break away and form the South African Students’ Organisation, a blacks-only student formation. The Black Consciousness Movement can be traced to that train ride. By a stretch, Sithole’s intellectual prospects, too, were made possible on that trip.

‘A whole world opened up’

In autumn 2003, Sithole found himself eking out a living as a train vendor, selling vegetables and loose cigarettes. It is a far cry from the politics professor he has become, making a career out of studying Biko’s thoughts and authoring books such as Steve Biko: Decolonial Meditations of Black Consciousness.

“My story began with a bursary I won in matric to study journalism at Rhodes,” Sithole says, sinking into his chair. The room dims as a cloud passes in front of the sun. “I remember dancing in celebration when an envelope with purple lettering arrived, but Rhodes University was writing to tell me that due to some issue with embezzlement, the SAB Miller chair fund was liquidated. I was devastated. I saw my dreams of going to university evaporate … I plunged into alcohol.”

That was in 2002. Sithole, who had passed matric with exemption, had to find something else to do.

Staring soberly through black-framed glasses, the 35-year-old academic pauses to reflect on his memories. His glasses gleam like the Zion Christian Church badge pinned to his workman’s denim jacket, over his heart. It’s a constellation of symbols that synthesises his politics.

“I started selling veggies in Naledi, Soweto, for a guy called Tiny around April of 2003. Through him I met another guy, Bra Tebza, at Joburg Fresh Produce Market in City Deep. He was the one that invited me to come and sell for him on the trains … A whole world opened up for me,” he says with the clarity of hindsight.

Slender smoksara

It didn’t take long for Sithole to become fully immersed in the mobile traders’ network, as the beret-wearing boy that commuting old ladies called “Slender”. He learned to project his produce purchases to meet expected daily demand; understood how to set his pricing to remain affordable but still profitable. “You know what else I learned? The power of potatoes. They are the price determinator for all veggies. Where potatoes go, the market follows!” he says, like a teen waiting for his punchline to sink in.

Sithole sold vegetables from Monday to noon on Friday, and pushed loose cigarette sales on Friday evenings. On these late rides, the first and last carriages of the train are called dumane. They are packed with recently paid workers on their way home, gangs of vendors counting their profits, gamblers, and some gangsters too.

“I would hang by the door and wait … Occasionally, a voice will call out: Slender, thumela (send through)! Stava-Stava was for Stuyvesant and eShatile (the married one), because of the gold band on its branding, meant Courtleigh. And if they called out eBandayo (the cold one), because of its cool menthol flavour, I knew to send through a single Craven A.”

Standing at the door, Sithole would simply respond to a voice and trust that the requested cigarette would find its way to the right hand, just as he had to trust that the payment would make its way to him through the packed carriage. Even known thieves didn’t mess with this system, Sithole says. “When you’re a smoksara (vendor), you must develop respect.”

There’s a communal spirit among regular train users. People generally know each other and stick to their regular carriages. The dumane attract neighbourhood scoundrels. There are carriages dedicated to mobile churches. The sound of bells and drums, hands and hollers pours out of them to the rhythm of the train.

Daily ritual

By the spring of 2003, Sithole says, he had abandoned the Naledi to Park station line to sell on the Joburg-Pretoria route. It was the most profitable line. “This was a painful time for me. People would snigger behind my back. Mean mamas would laugh at me saying, ‘Matric exemption is equal to tamati and onions.’ I acted like I didn’t hear them.”

Every day, as the train left the Pretoria station and passed Fountains Valley, Sithole would retreat to between two carriages. “I had this ritual. I’d stand there alone, looking at the big building of Unisa and say to myself: ‘One day, I will study at this place.’ It helped to keep my focus.”

In 2004, things began to change. The state-owned Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (Prasa), known then as the South African Rail Commuter Corporation, began crafting a new vision and strategy for modernisation.

Prasa proposed to build 7 224 new trains at a cost of R123 billion. It began by researching and defining the profile of a typical South African railway user. This research revealed what was already known, that in South Africa trains are used by the working class. The moneyed classes and their upwardly mobile middle-class cousins do not ride uMjanji, at best they use the pricey Gautrain.

The surveys Prasa conducted across six railway commuter regions – Cape Town, Durban, East London, Port Elizabeth, Pretoria and the Witwatersrand – indicated that the overall majority of passengers are black African (84%) and within the typical working age group of 21 to 50 years old. Cape Town and Port Elizabeth had a higher number of passengers that fell into the groups classified during apartheid as coloured and white.

Safety and police

The surveys revealed a perception among users that violent outbreaks and a general lack of safety were expected on trains. As such, there were more male commuters because of safety-related fears. The result was a revised safety and security system along with fare recovery measures on what Prasa called “priority corridors”.

Sithole and his fellow vendors noticed a sudden increase in police officers and outsourced security personnel on the trains. “In 2004, they started arresting us. It just became hard to sell on the trains, so I stopped,” he says, pausing as furrows crease his brow. He moved his small business to a street corner in Molapo, Soweto, and continued to save money.

“By the following summer, I was back on the train. This time as a commuter, on my way to register and study at Unisa.” We smile with the joy of vindicated struggles. Then he gazes off into the middle distance. We imagine there is another dreamer passing Fountains Valley, a vendor doing a balancing act between train carriages.