The story behind an iconic South African photograph

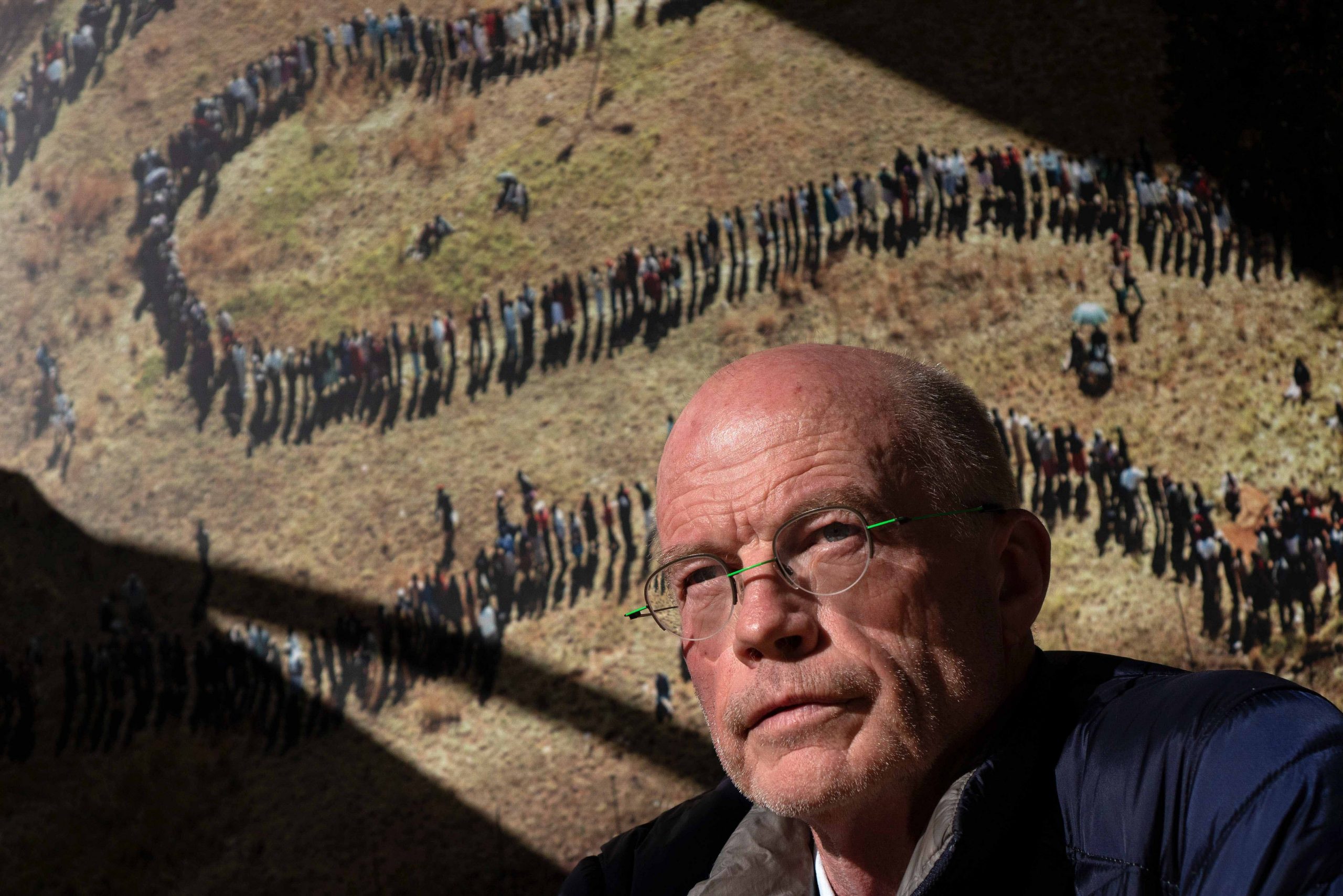

Denis Farrell’s aerial photograph in 1994 of a snaking queue of Soweto voters pipped that of Nelson Mandela casting his vote, earning him a Pulitzer Prize nomination.

Author:

16 May 2019

On 27 April 1994, Denis Farrell woke up around 4am. He had left the office around midnight the night before. His emotions were charged. This was a big day. The eyes of the world were on South Africa.

Farrell was – as he still is – a picture editor and he didn’t usually take pictures. Only if there was a need, and there happened to be a need on this day. Little did he know that by lunchtime he would have taken one of South Africa’s most important photographs. A photograph that showed indisputably how important freedom was to so many South Africans. It’s a picture that ranks up there with Sam Nzima’s photograph of Hector Pieterson as one of South Africa’s most important and iconic photographs.

It was still dark when he began the drive from Johannesburg to Pretoria. The plan was for Farrell to photograph then president FW de Klerk casting his vote at a school in Pretoria. Thereafter, he was to make his way to Rand Airport to hop on a chopper with Radio 702’s traffic man, Alan Matthews.

But just as everyone was setting up and taking their places in Pretoria, his pager buzzed with an important message. (At the time, a pager – or beeper – was a device that delivered short messages, similar to SMSes). “Drop De Klerk. Explosion at airport. Go and collect film.”

The explosion was a car bomb detonated at then Jan Smuts Airport in east Johannesburg, the latest in a deadly bombing campaign carried out by the far-right Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB, the Afrikaner Resistance Movement) in an attempt to derail the elections.

Farrell grudgingly left Pretoria. Now he had been relegated to the job of a runner, sent to collect another photographer’s films and bring them back to the office for processing. He probably wouldn’t even make it for the helicopter flight.

Just as he neared the airport, the dreaded pager beeped again: “Film has been taken care of. Proceed to the chopper flight.”

Excited again, Farrell describes the moment he got on the helicopter: “I kept expecting the pager to go off and send me somewhere else. We had to turn off all our electronic devices once we got in the helicopter. It was such a relief, at last, I couldn’t be disturbed. I just sat there and exhaled.”

Snaking queues

They took off. It was just Farrell, Matthews from 702 and the pilot. “Once in the air, it was calm. I could hear Alan Matthews crossing over on the radio. You could hear the excitement building up and feel a sense of relief because up until then, anything could have happened. It was so surreal.”

First, they flew over Katlehong and Thokoza where most of the violence had been. Through an open door in the chopper, he began shooting the very long queues he saw. “I was shooting quite a lot and had to change film. I kept thinking, ‘Please God, don’t let my bag fall.’”

Farrell was concentrating hard. Shooting on film, he didn’t have the privilege of being able to check his images on the back of the camera, like photographers today. When shooting from a chopper, it’s not always easy to get everything in sharp focus because of the thudding vibrations of the rotor blades. Then they swooped across southern Johannesburg to the mighty township of Soweto. As they hovered over Dobsonville, they spotted the huge snaking queue of people.

“It’s a school called DSJ Primary. I know this because I went there two weeks ago [in 2019] and tried to photograph it with a drone. It wasn’t a great experience. There was nobody there. It was much better in the helicopter.”

Pinpointing the location

About three weeks before the May 2019 elections, Farrell and his Associated Press (AP) colleague, award-winning photographer Themba Hadebe, sat down with Google Earth and several much wider photographs of the scene that Farrell had shot in 1994, to find the location of the iconic photograph. It took them about three hours, but finally they were able to pinpoint DSJ Primary School in Dobsonville.

“All morning I had seen massive lines of people, but this one was different,” he says. “I think it’s because this queue was snaking back and forth. The background was clear, making the image very graphic. Most of the other queues were more orderly. They ran in straight lines, next to buildings. It was more difficult to show the scale.”

Back in 1994, after Soweto, they flew over Joubert Park in the city centre and then north to Bryanston, where there was rumoured to be a queue 15km long. The queue was very long indeed, although not 15km, but it was difficult to photograph from the helicopter because of the tree foliage in the area.

After almost two hours in the air, they landed and Farrell was forced to activate his damn pager again. “Get back to office. Drop off film,” it ordered him.

He sped back to the office and dropped the film, then headed out to take photos in Bryanston from the ground. “The rush was suddenly back. It was like there weren’t enough minutes in the day,” he remembers.

‘Cool photos’

That afternoon, when Farrell finally returned to the office, he was greeted with a very understated compliment from Mike Feldman, the American senior AP picture editor: “Cool photos, Denis.” Farrell says, “I wasn’t walking around smiling like a Cheshire cat. There was no time to gloat.”

The following day it became clear that his aerial photograph from Dobsonville had had a great impact on international audiences. But not everyone was happy. “Everyone thought that the picture was going to be of [first democratic president Nelson] Mandela casting his vote,” said Farrell.

The Mandela picture did well. But over time, The Helicopter Pic, as it became known to insiders, proved to be the image that captured the energy and hope of that great day.

About a year later, Farrell was on his way to meet friends. It was the first anniversary of the death of Ken Oosterbroek, the chief photographer of The Star who was killed while covering the pre-election violence in Thokoza two weeks before the elections, and a group of his comrades were gathering to have a drink in his memory. But on his way out of the office, Farrell was told that the AP bureau chief, John Daniszewski, wanted a word with him. “I wondered what I had done wrong, but he informed me that I was one of three photographers who had been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

“I had to be at the office to hear the announcement. There were bottles of champagne and everyone gathered around. Then the announcement came in that I didn’t get it. I wasn’t devastated. It was disappointing, but we still drank the champagne,” he laughs. “And they finally gave me a new bag of camera gear. I had been using everyone else’s reject cameras and lenses until then.”

Farrell worked the elections again this year and what he saw 25 years later is telling: “I flew over there again. I saw about five people. That was disappointing.”