The slow violence of sugar

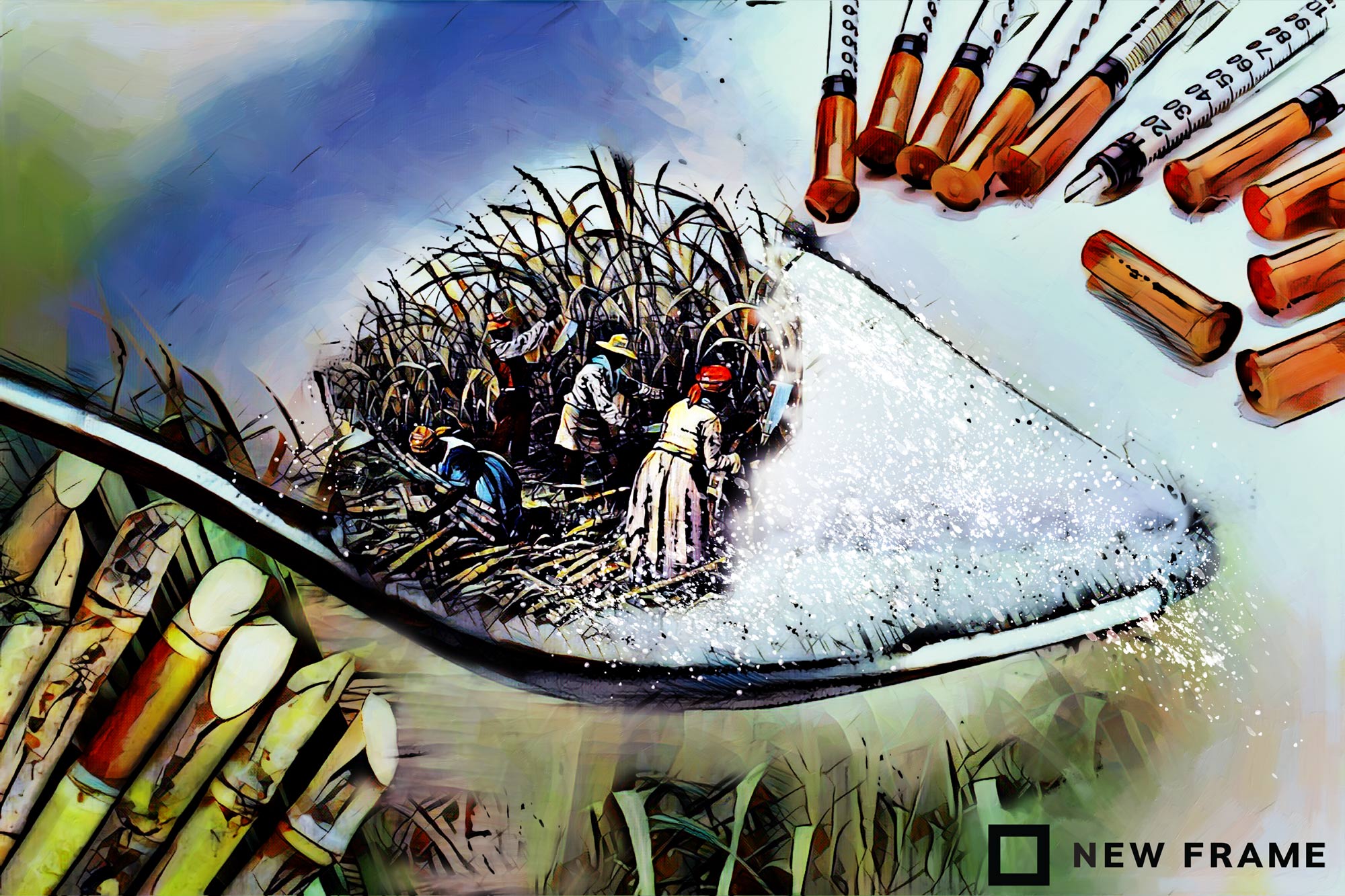

South Africa’s obesity and diabetes epidemics today can be traced to an accumulation of violence over time, starting on the early sugar plantations of colonial Natal.

Author:

27 September 2021

Sugar, like gold, rubber and oil, is a commodity that has produced immeasurable human suffering. Sugar cane was first domesticated in New Guinea and China around 8,000 BCE. The process of refining cane juice into sugar crystals was first developed in India and from there sugar spread to Persia and then, via the Arab world, into the Mediterranean. The Arab invasion of Spain in 711 introduced sugar to Europe and Europeans first became producers in the Levant after the Crusades.

By 1650, sugar featured prominently in the daily lives of English nobility. The brutal relationship between the Spanish, Portuguese, French and British Empires and their colonies is central to the history of how sugar became a global commodity, as anthropologist Sidney Mintz has shown in his book, Sweetness and Power.

As a plant commodity, sugar was foundational to the Atlantic slave trade and the broader colonial project. But, as Mintz notes, forced labour preceded the transatlanic slave trade. Indentured labour formed an integral part of the Moroccan sugar industry as early as the 10th century, although it was Spain “that pioneered sugar cane, sugar making, African slave labour and the plantation form in the Americas”.

The lineage of sugar includes its use as medicine, as a spice, for decoration, as a preservative and as a sweetener. Though first used as medicine and to preserve food, sugar reached its peak as a condiment in the 16th century. Its status then began to change as it became ever more associated with its decorative functions, which spread “through continental Europe from North Africa”, according to Mintz, while percolating “downward from the nobility” to ordinary people. Sugar lost some of its symbolic meaning as its availability to all in society acted as a leveller of status. Simultaneously, it became increasingly common in modern diets.

The desire for sugar spread steadily and its incorporation into diets increased to make up about a fifth of the caloric intake of the average British citizen by 1900. This “hunger” for sugar is more peculiar than it may at first seem as Homo sapiens is “one of the few species that can taste sugar and has developed to physiologically associate sweetness with life, survival, freedom and all that is good”, writes Black studies scholar Alexander Weheliye in Habeas Viscus.

So how did sugar come to occupy such a central role in daily life?

The value of sugar had increased dramatically in England and Wales by the start of the 18th century, overtaking that of tobacco. Consequently, slavery expanded rapidly in the English colonies.

England, which had learnt from Spain’s endeavours, “fought the most, conquered the most colonies, imported the most slaves” and “went furthest and fastest in creating a plantation system”, writes Mintz. The most important product of this system was sugar. The pervasiveness of slavery did not lessen until the Haitian Revolution at the end of the 18th century, which saw the largest drop of all time in sugar production and marked the beginning of the end of slavery.

Sugar played a major role in export earnings for a number of countries, but foremost for Britain. It also contributed to the production of alcohol, formed part of elaborate tea ceremonies, was used to create sweet treats and provided energy to dispossessed workers in European factories and on plantations. The combination of sugar’s value as a luxury food, its mass production value and the sense of wellbeing it engendered eventually led to rich and impoverished people aspiring to have sugar, and have it in large quantities. As a result, it “realigned aesthetic values” and “changed cultural appetites”.

A desirable product

Sugar was not found naturally in South Africa before the British occupation. But, by 1850, the first mill had been established on the Compensation Flats in colonial Natal, and by 1852 the Jane Morris had sailed into the bay with a cargo of 15 000 cane tops. As in other parts of the world under British rule at the time, such as Mauritius and parts of the Caribbean, sugar production in Natal initially relied on indentured labour from India. Later, much of the work on the plantations was undertaken by migrant workers from emaMpondweni.

Sugar became a sought-after product in southern Africa, quickly transforming into a common food rather than a specialised commodity. Sugar is so prominent in modern diets that it contributes significantly to obesity, a risk factor in diabetes, which around 3.5 million South Africans are said to have. About five million more are estimated to have pre-diabetes.

The histories of obesity and diabetes are often obscured by marketing that claims a natural goodness in sugar. Some of South Africa’s most-loved advertisements are for Coca-Cola, Ultramel Custard, Nestlé Bar One and Oros, showing the powerful emotional trade-off between adverts, comfort food and a sense of wellbeing.

This sense of wellness is derived from sugar in part because it stimulates the pleasure centres in the brain and releases chemicals, one of which is dopamine, a substance vital for physical and mental health. Dopamine is also largely responsible for the “reward” sensation that humans experience. This sensation can drive addiction because the brain gets accustomed to the dopamine response generated by the consumption of certain substances, for example carbohydrates such as sugar, so that more of the substance is needed to achieve the same effect.

Other reasons that sugar is associated with wellbeing are more complex than a dopamine trade-off and are influenced by the social and psychological contexts in which people find themselves. This complexity also has to do with the meanings that have come to be associated with sugar: sweetness, comfort and happiness. These meanings, while varied, overlap in questions of “slow violence”, a term coined by academic Rob Nixon to expand our understanding of harm.

Slow violence takes seriously how harm often becomes detached from its original causes so that its impact is elusive even though it may be widespread. Nixon says that whereas violence is usually perceived as “an event or action that is immediate in time, explosive and spectacular in space” – and therefore visible and tangible – slow violence “occurs gradually and out of sight”.

The lineage of sugar

If we think of sugar plantations in terms of an accumulation of slow violence rather than as events in history, there is a clear line between displaced labourers in the factories and plantations, the owners of these plantations and the wealth that sugar created for them, and the current diabetes epidemic. Another aspect that changes is the way we think of social justice, because slow violence demands an understanding that accounts for damage accrued over time.

The sometimes visible, sometimes invisible hand of sugar is evident in the violence that emerged from the sugar plantations. Devastatingly brutal, they were worked by enslaved and indentured people. This violence evolved over time into the slow violence of obesity and the contemporary diabetes epidemic, one that affects impoverished and rich people alike.

Part of the imperceptibility of this epidemic comes from people hiding their diabetes status because of its association with being “overweight, lazy and guilty of bringing the disease upon themselves”. They are connotations that often lead to diabetics feeling shame. Changing such perceptions forms part of the social justice project of redressing the slow violence of sugar plantations, which continues to accumulate into the present.

Chantelle Gray is an Associate Professor in philosophy at the North-West University working at the intersections of gender, race and radical politics.