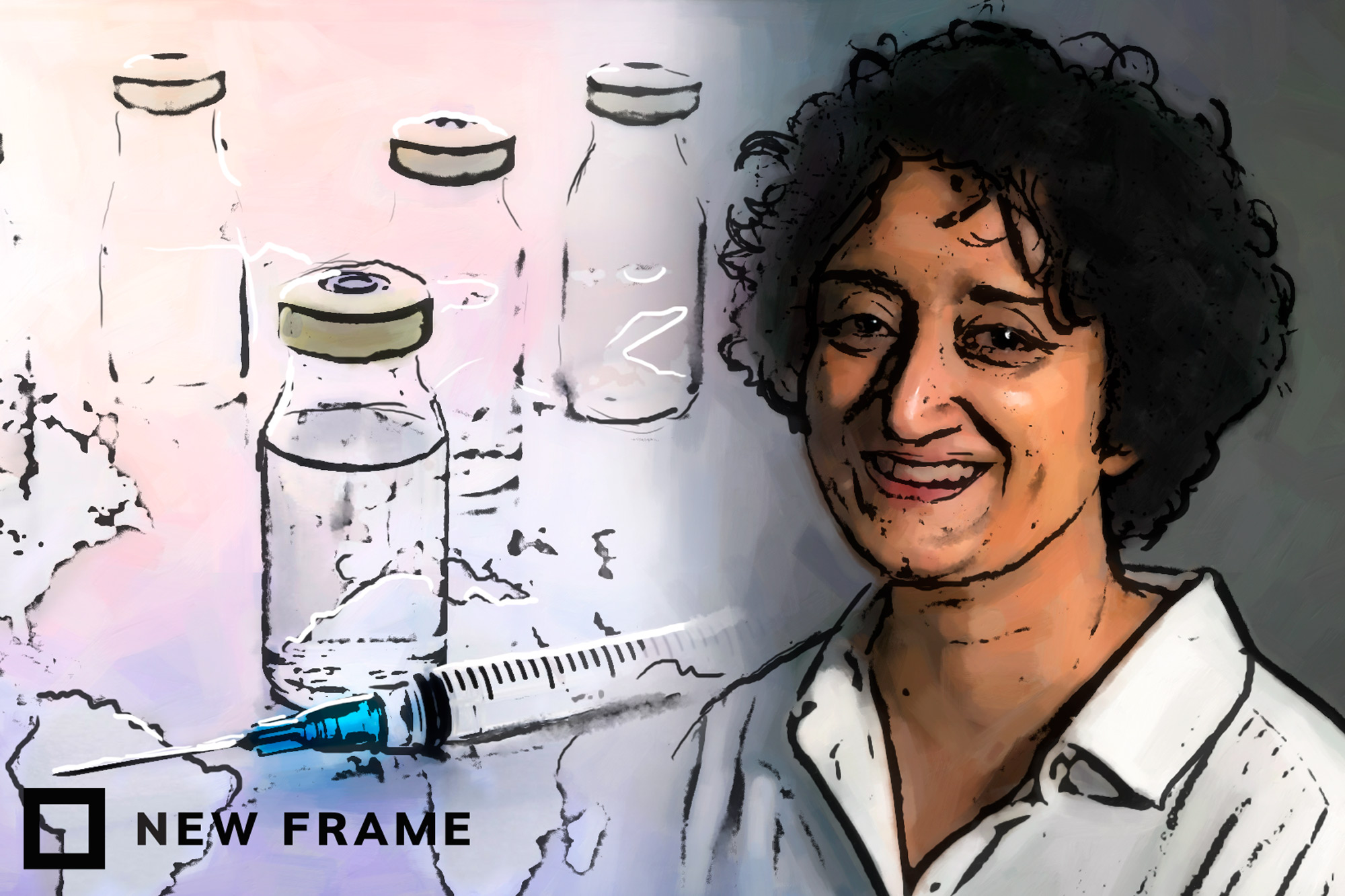

The scarcity and expense of Covid-19 vaccines

Fatima Hassan, founder of the non-governmental organisation sounding the alarm bells over vaccine procurement issues, speaks about pricing, transparency and rollout strategies.

Author:

2 February 2021

At last, a million doses of the Covid-19 vaccine from pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca arrived in South Africa on 1 February 2021. These first doses were manufactured by the Serum Institute of India through a sublicensing agreement. The doses will be held in cold storage and tested before they are given to healthcare workers on the frontline of the pandemic.

In the past few months the government has made a strenuous effort to procure the first batch of Covid-19 vaccines. Fatima Hassan is the head and founder of the rights protection group the Health Justice Initiative. She discusses the government’s rollout strategy, the lack of transparency, vaccine scarcity and how this affects the Global South, pricing and profit margins, and how rights groups warned the government about potential supply problems.

Tebadi Mmotla (TM): What is your take on the government’s rollout strategy for the first of the Covid-19 vaccines?

Fatima Hassan (FH): The little … we know … is that the first batch of vaccines are for healthcare workers … But when you speak to doctors and other workers on the frontline in healthcare, I think the one part that is confusing is whether [the government is] going to administer the 1.5 million doses first [500 000 of which will be received later this month] and then wait for supplies for the second dose or whether [they are] going to do this as a two-dose batch for up to 750 000 workers. [To be effective, two doses of the Covid-19 vaccine must be administered.]

There are also some concerns about whether the number of healthcare workers and workers in healthcare settings across public and private sectors have been accurately collated. In the next week, you will see a lot of issues emerging potentially around the vaccines actually being administered in multiple parts of the country simultaneously, because the idea – from what we’ve been told by government and the private sector who are involved in this acquisition – is that all healthcare workers will be able to get the vaccine at the same time.

Related article:

There are also issues around each different vaccine that may be approved here having different efficacy levels. Obviously, it’s like a moving set of goalposts because, while vaccines are being administered, there are also new results and data coming in. And we also have a new variant in South Africa [and] in the United Kingdom … There’s still a lot that I think clinicians and doctors are really urgently looking at and working on.

It’s important for our frontline to be protected. And we have to hope that the first phase goes off in a way [that] really prioritises the principle of equity … All healthcare workers – whether in the public or private sector, in hospitals [or] clinics – that are providing health services and … doing all this important work [at] this time. [They should all] be able to get vaccinated.

TM: Is the government doing enough to address the issue of vaccine scarcity?

FH: I think the issue of scarcity is a bit more complex because scarcity is also self-created by the global pharmaceutical industry, because they are refusing, in many cases, to share the vaccine know-how and technology. So scarcity and limited supplies became an issue for the European Union [EU] now in the last week to the point where the EU … just passed a ban on exports of supplies to certain countries. Some countries are exempt.

So scarcity is now an issue that is gripping … the entire world. And that’s because of what happened in the last few months, even though places like the EU had signed these advance market commitments (AMCs) and were guaranteed a certain initial amount of base volumes of dosages, they have not yet received all of it. And they are asking like, ‘Why? What’s going on?’ And part of the reason for that is … [companies] thought that they … alone [were] going to meet all of the demand and [so they did] not sublicense other companies [to help manage the load and] scale up the manufacturing for them and for [other companies]. That is now the situation …

And so it’s a real reckoning moment, and it is what we’ve been saying for months. If you don’t share the technology and the vaccine know-how, then nobody else can help you to make it. [When] you … rely on one or two suppliers … you will have limited supplies and scarcity … [which] means that it takes you longer to vaccinate the whole world. That’s when you then also have to deal with variants and mutations. The longer it takes to scale up manufacturing by multiple suppliers, [the more intractable] this problem [becomes].

Related article:

The EU has now realised that they have to address scarcity, because they have certain agreements. They’ve published a redacted version of the AstraZeneca contract with the EU. It also maybe puts things [into] perspective … [for] why [in] some middle-income [and] low-income countries, AstraZeneca through Oxford University too, has segmented the global market. They were supposed to supply Europe and the United States of America – … and other rich nations – and have Serum [Institute of India]… supply the Global South. They have given this one licence to Serum, [and there] may be one other licence [available].

But … there is no transparency. You don’t really know what the terms and conditions are.

TM: Does the lack of transparency leave room for people to feel hesitant about taking the Covid-19 vaccine?

FH: Yes. In any part of the world, [when] a government or those responsible for researching, acquiring or distributing vaccines are [not] transparent [in] sharing information, that’s when it’s fertile ground for disinformation and conspiracy theories.

So should the South African government do more right now? Yes. It can actually start asserting its authority and consider using state licensing measures. We now have results from Johnson & Johnson [an American multinational corporation involved in vaccine development], and some of the results from the Novavax [an American vaccine development company] trial too.

So you’re in a much different situation than you were in December 2020. … Now you can also see that there are major supply bottlenecks in the rest of the world as well. That means it’s going to potentially take longer for those supplies that were … promised to us to come here. So what do you do? What measures can you take to ramp up manufacturing, to demand scale-up of supplies for the whole of Africa and the rest of the Global South? Because even if we got 40 million [full vaccine doses] tomorrow and you vaccinated everyone that needs to be vaccinated [to achieve population immunity], you are [on] a continent where [there is little] coverage.

Related article:

Covax is saying we can only maybe help up to 27% of people in low-income countries. They’re [talking] about Africa, right?

Yes, governments all around the world have to do more. Last week, we saw the EU, which was very surprising, really taking on the pharmaceutical industry in such a public way [and], in some cases, a punitive way. That may be [showing] other governments in the Global South [that], well, if the EU can take on AstraZeneca and others in this way, then why are we so scared of taking on AstraZeneca, Pfizer [an American pharmaceutical corporation] or Johnson & Johnson?

The other thing linked to supply is that in South Africa you can’t supply something that’s a vaccine unless it is registered for you. You have to … give your data to the regulator. So just because somebody wants to sell me a vaccine from Russia or China, I can’t buy it or procure it unless … the data [is] confirmed to be safe and effective. If the Chinese are refusing to share the data, or if Moderna [an American pharmaceutical and biotechnology company] is refusing to submit its dossier, then what do you do then? You have an international crisis moment.

Why are companies picking and choosing where they want to go in a pandemic? They should go everywhere. Everybody should share the technology.

The question about the government is why is the procurement – which is such a multisectoral, complex thing residually, you know, the negotiations, the dealings which also include vested political interests and powers – why is it still residing in the Department of Health? It is not just [a] Department of Health issue. Yes, they have a vaccine acquisition task team with the private sector for medical schemes, business, National Treasury representatives, etc. But … I think it’s shortsighted on government support that this is still being driven and located in the Department of Health. They should be giving medical and clinical advice around what they need [and] why they need it.

TM: Pricing has become an important issue for the Covid-19 vaccine. Why is it that countries like South Africa are paying more than other nations?

FH: We don’t know a lot. What we do know is … based on a mistaken tweet by a Belgian minister [about] the EU prices. The EU [has] not confirmed all of its prices either, nor have the other ones.

It’s all speculation because there’s no price transparency. Covax has not told us what its prices are. So we know that something is wrong, but we don’t know the extent because nobody will share the data.

Related article:

The first problem is that we don’t know what the real no-profit prices are. We also don’t know what the markups are for the delivery – or are we being charged a premium because of this weird theory that we were not part of the research and development, yet we were part of a clinical trial?

That’s what happens normally with the industry, because there’s never been price transparency in the pharmaceutical industry and our medicine system in South Africa especially. And in South Africa, we’ve always had two different prices for the same medicine, the public- and the private-sector price. And there’s very little price transparency and scrutiny. We don’t even have a global benchmarking system. And so the concern is that we now sign a contract with Covax, which is an unelected structure [and thus does not serve the South African population but rather benefits the supply company]. I have nothing to do with it as a South African citizen. So how do I hold [both the supply company and the South African government] to account for its three different price systems? But my money goes into it, and your money too.

TM: What has been the role of non-governmental organisations throughout the vaccine procurement process, especially your organisation, the Health Justice Initiative?

FH: We have been raising the alarm bells for a very long period … For four months, we’ve been warning that we needed more time and more planning around the fact that you’re likely to have a global supply problem. And that you are likely not to have cooperation from the pharmaceutical industry.

My organisation already from October and November 2020 had been raising this explicitly and also started engaging in correspondence with the department, and in the different ministries, [which] did not respond… until the reports emerged then indicating that we [were] threatening litigation. So we are still engaged in that process because we don’t believe that there’s been sufficient sharing of information and transparency around various aspects of the plan. Just yesterday our legal representatives sent a detailed letter requesting information.