The political is personal for Sam Fender

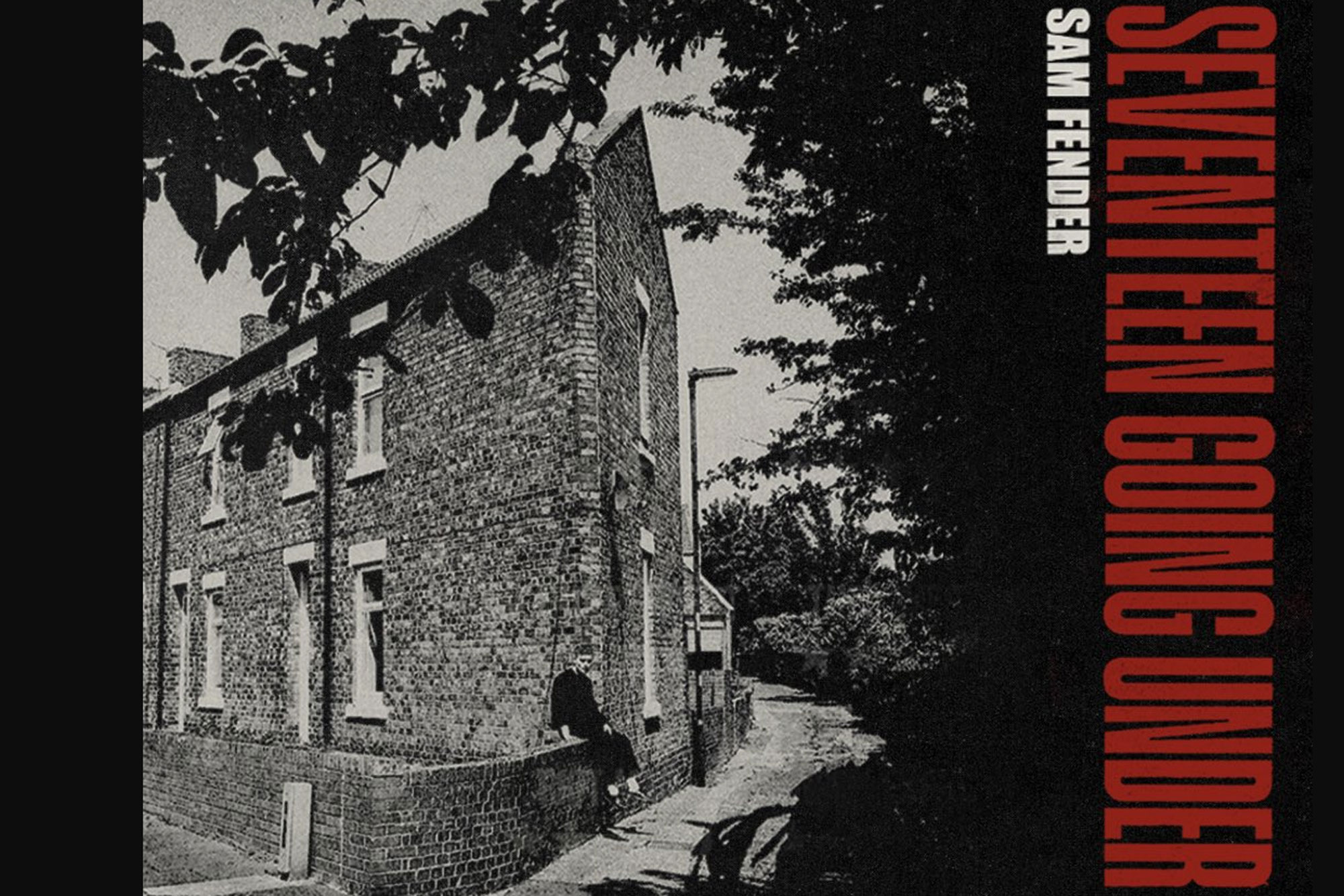

The British artist’s latest album reflects the self-awareness that he has developed in the past decade, as he refuses to succumb to despair on Seventeen Going Under.

Author:

30 March 2022

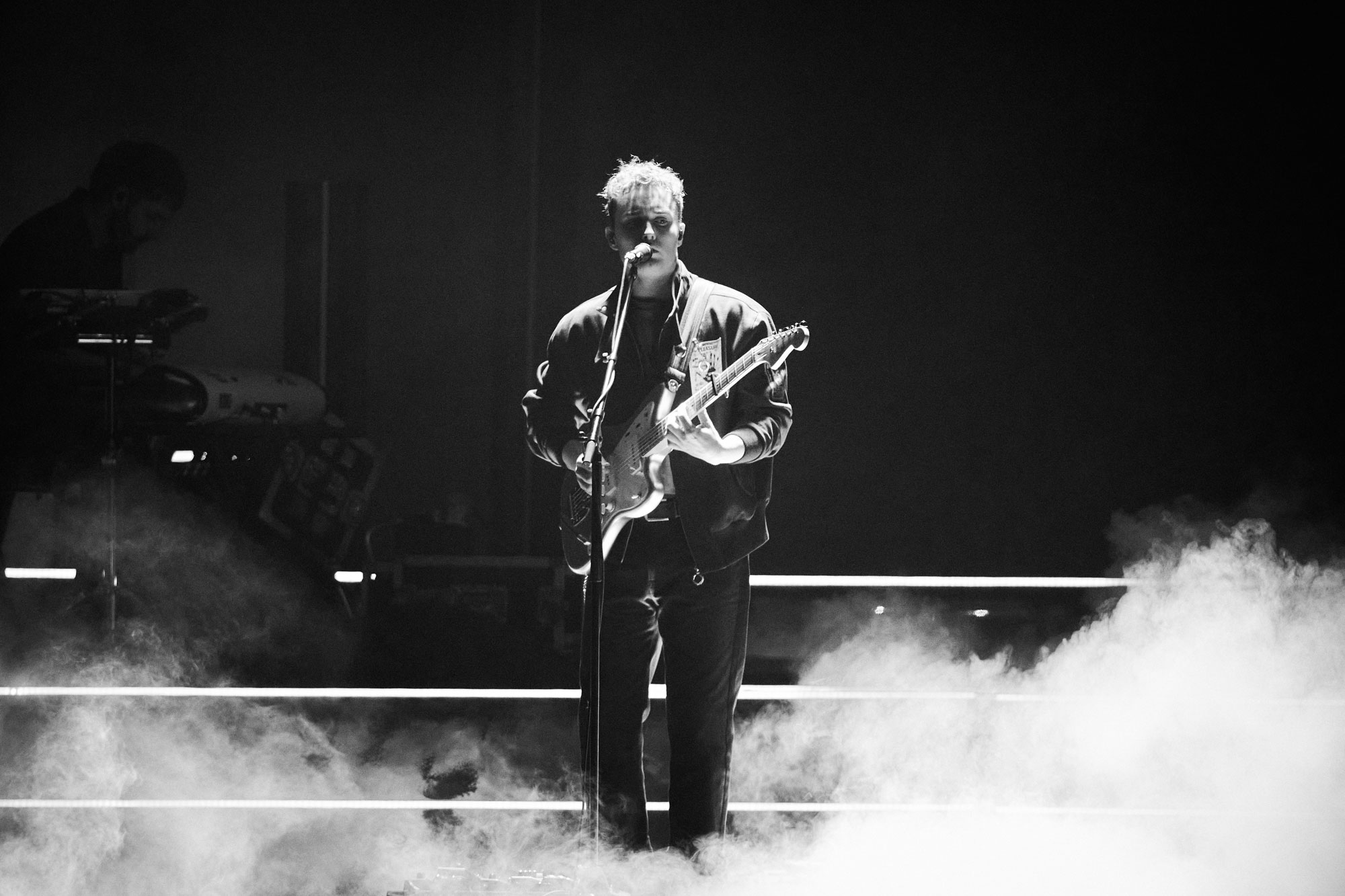

Sam Fender’s Brit Awards success is as much a celebration of the young singer-songwriter as it is a recognition of who and what he chooses to foreground.

“You want to make us sad on a Friday afternoon?” my mom laments from the driver’s seat, rising above Sam Fender’s cathartic outpour on The Dying Light. “I’ll never understand why you choose to bring your mood down. Play happy music please.”

Beneath the hint of toxic positivity, I guess there is some truth in her words. At the tender age of 27, Fender has endured a lifetime of hardship. He has watched his once-distant mother live with a chronic illness and battled one of his own. He grew up in North Shields, a working-class town in northeast England, with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. And he has grappled with strained interpersonal relationships, both familial and social.

Related article:

Each of these on their own would be enough to make the best of us retreat inward, descend into resentment and solitude. Not Fender, though. Transforming these experiences is what has catapulted him to Brit Awards success – winning the fan-voted Best Rock/Alternative Act award and being nominated for Artist of the Year and Album of the Year – and soon to the Glastonbury Festival stage.

Seventeen Going Under is a manifestation of his refusal to “go gentle into that good night”.

A sense of triumph

The album is Fender’s journey back to himself and it is the opening and title track that tells us that for Fender, the old adage holds true: what’s past is prologue. The evolution of his anger – from unbridled indignation at 17 (“I spent my teens enraged,” he sings) to a channelled sense of purpose at 27 – is underscored by the thumping pulse the melody bursts into about a minute in. Fender experiments with dynamics in this way throughout the album, oscillating between pulsating highs and sentimental lows, to keep his message foregrounded and evoke the air of triumph that pervades the album.

You have to listen closely to fully appreciate that triumph, though. The album’s title is the first clue that for much of Seventeen Going Under, Fender is on the verge.

“I must admit, I’m out of bright ideas to keep the hell at bay,” he confesses on The Dying Light, accompanied by delicate and stripped-down piano keys. There’s the sense that for Fender, a near-death experience – his potentially fatal illness – propelled him to make the most out of living. And integral to that is writing meaningful, relevant lyrics. He’s not completely past any of his struggles, but beneath his pain lies a trace of hope. “Reaching for a light in a gauntlet of toxic paradigms,” he sings on Paradigms.

Related article:

The artist sets himself a monumental task entering the musical Sistine Chapel that is the intersection of song and protest. Yet we know for sure that his is not the enchanting melody blended with universal messaging that marks Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, the torturing reverie of Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit or the delicate yet powerful A Change is Gonna Come, Sam Cooke’s anthem for oppressed people everywhere.

Fender’s is closer to the counterculture-defined political rock epitomised by songs such as John Lennon’s Imagine or records in the same vein as Bob Dylan’s The Times They Are A-Changin’. It would be truer to say that Fender is closer to the anti-establishment punk championed by the Sex Pistols, or that he comes close to emulating his idol Bruce Springsteen. But still, none of these feel right.

Personal experience

Moments of technical brilliance stand out on Seventeen Going Under, but it is clear that Fender’s prize is not experimental variety. That many of his songs mirror each other feels intentional. Fender identifies his style of fast-paced electric guitar and snare-paired rhythm. He strips down his sound to make way for the album’s true focus, its lyrics. Is it for better or for worse that he veers away from the insistence on balance shown by his forerunners and uses instrumentation almost exclusively as an accessory? Is it to his credit or his detriment that Seventeen Going Under, at its most expressly political, privileges message over music, embraces explicitness over artistry?

It has been said about both of Fender’s albums that he is successful when he lets personal experience guide narrowed introspection, and falls short when he branches outward. Yet to create such a dichotomy is misguided. For Fender, the slogan championed by that now famous generation of feminists is true: the personal is political. In his case, the converse is more accurate: the political is personal.

There is no line between the anecdotal and the sociopolitical on Seventeen Going Under. Fender’s feelings of helplessness and despair about his mother’s condition are simultaneously an expression of his disillusionment with the inhumanity that runs through British public bureaucracy. “I see my mother, the DWP see a number,” he sings. The acute abandonment and alienation he conveys – “I’m alone here even though I’m physically not” – are inextricably bound to his proclamation that “the left wing have abandoned the working class”, that the “they” he lambasts on Aye, that infamous 1%, has ostracised him individually as much as they have ostracised the 99% in which he includes himself: “We are the scum who overstayed our welcome.” And finally, that the bullies he has at long last built up the courage to stand up to – “But I would hit him in a heartbeat now” – are an evocation of a failed government made up of bigoted, self-absorbed, ineffectual… well, bullies.

The little guy “betrayed by every headline” on Paradigms is the same little guy “bleeding out for a caricature of a ’50s salesman”. He is as much an individual as he is proud to join hands and declare “we are the 99%”. What’s more, Fender is him too. Perhaps that is his true mission, to humanise. To give a sound and a face to all those “the very few” would prefer to ignore, to make his mother more than a number.

Scattered among these attempts are moments of musical ingenuity. Saxophone meeting electric guitar for the latter half of Mantra and the 1980s jukebox atmosphere of Last To Make It Home shine bright. At his best, Fender intertwines both these features as a way of rooting us in reality. We bop our heads and tap our feet as we come to terms with society’s ills: who is affected and who is culpable.

A lesson for the young

There is no debating that Fender is gifted. Electrifying guitar riffs animate the album and his vocal range impresses, making his emotions palpable. But where there was prescience in the Fender who wrote Hypersonic Missiles – “My mind is always troubled with where have I been and where am I going” – there is maturity in this Fender, and both were born of his most enduring quality, his self-awareness. In the album’s most impassioned lament, he boldly declares: “I’m not a fucking anything or anyone.”

Fender has grown out of the need to flood his songs with buzzwords or present himself as the all-knowing paragon of political correctness that shrouded most of Hypersonic Missiles. The Fender we find is willing to concede that he hasn’t “been the best of men. Morality is an evolving thing.” He’s introspected enough – “Picking fights with my reflection” – to position himself in the world around him. Most importantly, he’s kept his despair from getting the better of him. In his own words, “I catch myself in the mirror.”

Related article:

Music has that rare quality of being both sufficient in and of itself, and a means to an end (I listen to Otis Redding for different reasons than I listen to A Tribe Called Quest or Corrine Bailey Rae). I’ll keep listening to Sam Fender’s Seventeen Going Under because it reminds me “to never get used to the unspeakable violence and the vulgar disparity of life around me”, to borrow that charge laid out by Arundhati Roy. The urgency in Fender’s sound, accompanied powerfully by bold assertions, is a way of keeping me (us) from becoming desensitised or from slipping peacefully into acquiescence. Fender makes it impossible for you to claim “you did not know”. Isn’t it fitting that his lyrics are being used to teach year 9 English students at his alma mater, Whitley Bay High School? That his music resonates with young audiences is testament to the fact that Fender gives of himself and his own experience in his music to give expression to a wider, collective voice, and that for him, the two are entwined.

Unfortunately for Fender, there is no angel that will fall in Lothian and “fix the problems he cannot fix”. But perhaps, through musicians such as Fender who refuse to turn away from the world – to separate art and society, the personal and the political – more people will be driven toward action.

Fender has time to perfect his craft. What matters is where he is looking, with whom and what he concerns himself. That can’t be rehearsed. All we can hope is that, as he sings on Angel in Lothian, he continues “to trust” his eyes.