The myth, music and magic of Club Pelican

By its very existence, Soweto’s first nightclub defied apartheid. And as people of all races mixed, many budding musicians got the chance to fine-tune their talents too. Now a new album honours it.…

Author:

18 February 2022

Behind the train station just off Pela Street in Orlando West, Soweto, stands a husk of a building. It houses an unsung but legendary space shrouded in myth: Club Pelican.

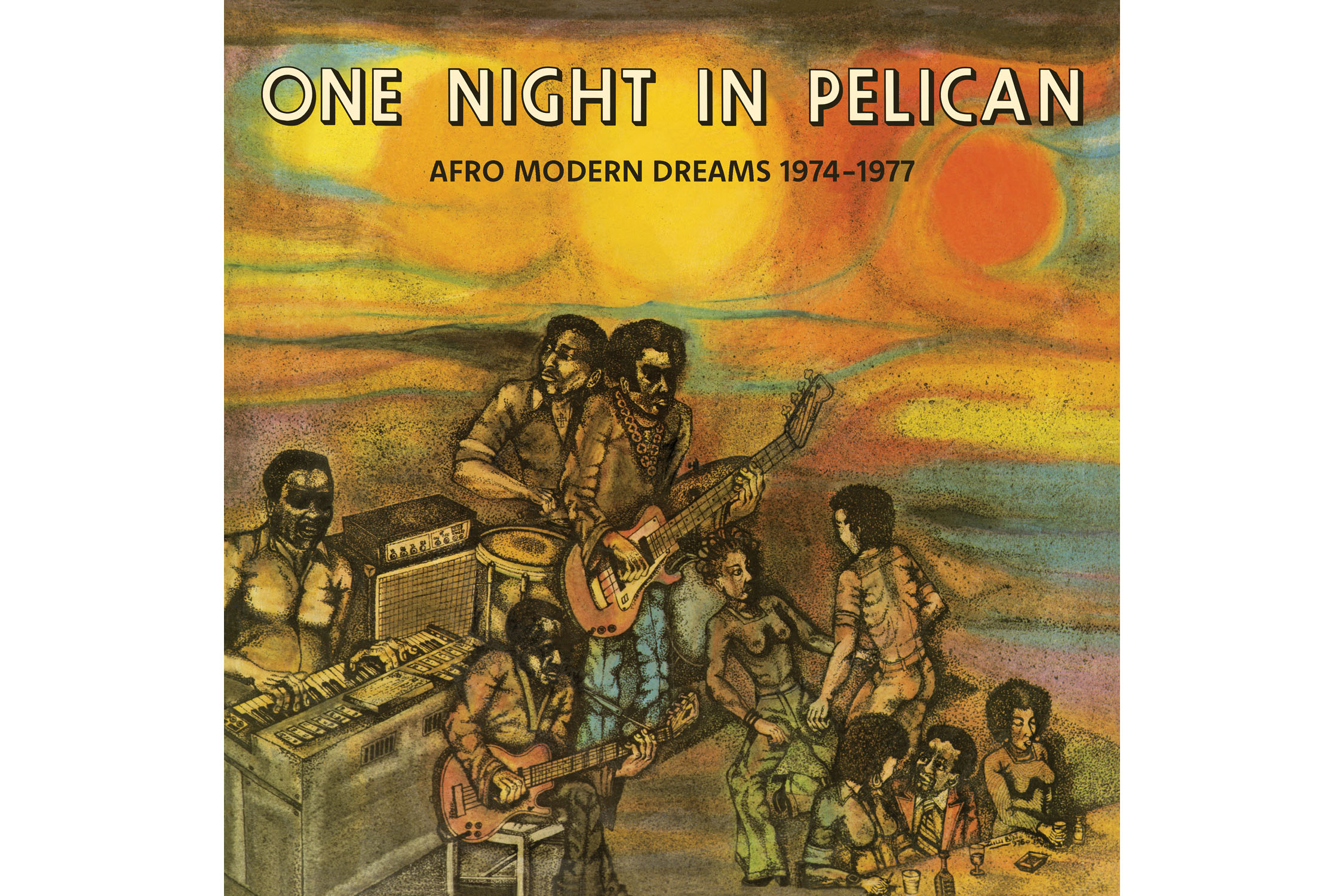

The sentiment about the club is that there has never been, nor will there ever be, a place quite like it. Soweto’s first nightclub deserves its own movie, book and chapter in school curricula and should be a heritage site. But for now its memory is preserved through the compilation album One Night in Pelican – Afro Modern Dreams 1974-1977, recorded by bands who performed at the venue during this time. Released in December by Matsuli Music, the record has spurred new interest in this forgotten but rich legacy.

The Pelican is significant for its role as a nurturing hub for hundreds of musicians from all over South Africa and because its very existence defied apartheid laws. It was founded by brothers Lucky and Leo Michaels. “We travelled a lot to Lourenço Marques [Maputo] at that time. It was famous for its nightclubs which all ran along one street, like you’d find in Las Vegas. You’d go from one club to the other. So this idea was born from there,” explains Leo.

Inspired by the names of clubs like Mozambique’s The Flamingo, they settled on Club Pelican. To finance it, the brothers ran a small brake and clutch business for a year. While Lucky was the face of the Pelican, Leo, who was 14 years younger, remained behind the scenes taking care of business.

In May 1970, the club opened its doors, according to Leo. It originally started with a membership model. Run as a kind of upmarket shebeen, the clientele were local doctors, lawyers and accountants – fashionably dressed in bell bottoms referred to as botsotsos – looking for entertainment.

But the story of the Pelican goes deeper. It is a story about family and one that mirrors South African history too.

The Michaels-Tandy family

Michaels was a popular restaurant in Johannesburg located on the corner of Delver and Marshall streets in Marshalltown in 1947. It was one of the only Black-owned restaurants in the city. Close to the courts, it was also where the young lawyer Nelson Mandela would regularly eat lunch.

The restaurant was owned by Michael Tandy, who was originally from Zimbabwe. Patrons would greet him as “Mr Michaels” and eventually his sons Leo and Lucky changed their surname to Michaels, while their other siblings kept Tandy. Such was the case for many families living under apartheid.

Tandy also owned a massive building in Soweto near their home. A few of his businesses, including a fish and chips shop called Luckys, operated from there. It was here that the brothers decided to open the nightclub, which Leo describes as “a whole family effort” because it involved his father, mother and sisters in its early days.

Though many journalists, writers and photographers passed through the Pelican, very little documentation exists today. “But, you know, you never really thought of things like that as you do today,” Leo says regretfully. Recalling the place from memory, he vividly reconstructs an “open space with tables and chairs”, “a kitchen at the back … and at first a tiny little stage in one corner on the left”.

By 1976 the Pelican had grown larger: moving the stage upstairs tripled its size. Leo was 20 years old at the time. “I ran the business, making sure the bar is operating well … I used to do a lot of running around, picking up and dropping musicians who often didn’t even have a car to travel with,” says Leo, now 69.

By contrast, Lucky, described as flamboyant and stylish with a magnetic personality, “kept the customers happy”. Before starting the Pelican, he travelled extensively through Africa and stayed in Zimbabwe and Mozambique. Lucky spoke eight languages, including Shona and Portuguese, and was also great friends with Marcelino dos Santos, one of the founders of the Liberation Front of Mozambique, Frelimo.

As a result, he attracted all kinds of musicians and patrons to the venue. “Lucky was quite popular and spent most of his weekdays roaming – we used to call it shebeen crawling. He would go to all the shebeens and kind of tout customers there and get them to come to the club on the weekend,” Leo recalls.

The Pelican was one of only a few multiracial clubs in the country, illegally so. “It was because Lucky communicated with so many white women and brought them and their friends to the club. We had so many whites coming to the club. So much so that we used to have raids from the police to arrest whites and coloureds and take them to the police station and charge them for not having a permit to be in the location.”

A grooming hub for musicians

In Johannesburg in the 1970s, spaces such as Dorkay House, the Bantu Men’s Social Centre and Kohinoor World of Music were popular meeting hubs for musicians. The Pelican soon became another.

“There’s hardly a jazz musician from South Africa that didn’t come through the Pelican … they all passed through at some stage,” says Leo. “They were there every weekend. They virtually slept there. It was really a breeding ground for all musicians who wanted to get into the music scene.”

The music programming was particularly diverse, running from Friday to Sunday. Nights ran through to the morning. While initially beginning with bands doing American pop covers, around 1973 the programming shifted towards jazz on Sunday afternoons. “That’s when we started attracting all the top musicians from everywhere,” Leo says.

A new music scene emerged. Respected trumpeter Stompie Manana remembers his first time entering the venue. “It was a bit dark and dingy,” he says. Deep inside the venue he saw pianist Tete Mbambisa and trumpeter Dennis Mpale, two jazz heavyweights, playing as a duo.

When the legendary saxophonist Winston “Mankunku” Ngozi moved to Johannesburg, a house band was formed that included the late guitarists Sipho Gumede and Baba Mokoena. Following this, a band called the Durban Expressions – made up of pianist Bheki Mseleku, guitarist Themba Mokoena and other musicians – had a brief residency. They would do pop covers but eventually started playing more jazz. “Things were really happening,” Mokoena says about the vibrant scene he found.

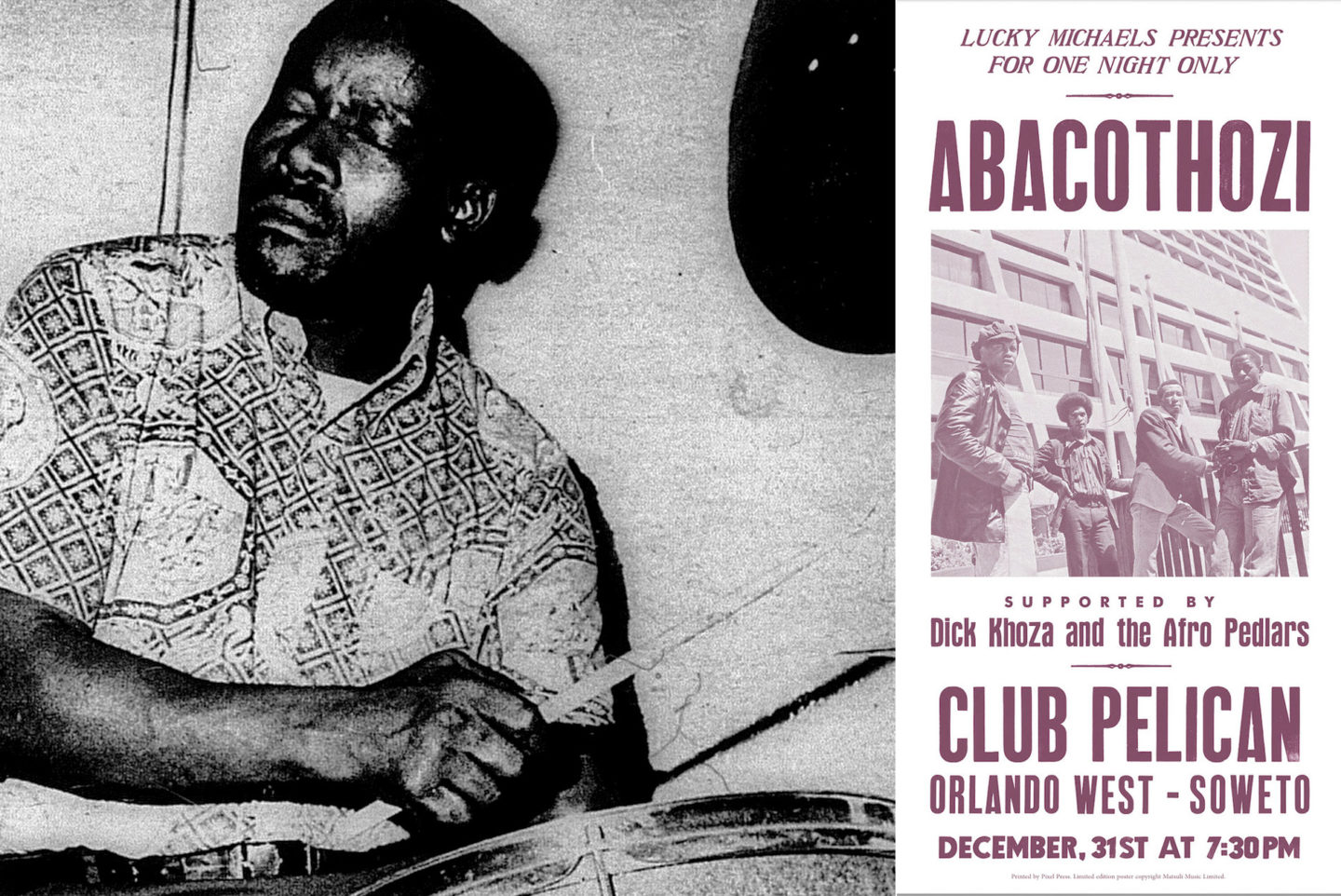

Lucky chose drummer, arranger and composer Dick Khoza to be the stage manager and leader of the house band, which became known as the Afro Pedlars. Khoza was a musical genius, described as being disciplined and strict, and he was crucial for nurturing many bands that became prominent in the 1970s.

The Pedlars had core members but operated fluidly, constantly morphing as musicians came and left. Some would drop by for a session just to jam. At different times the band also included Mac Mathunjwa on keys, Manana on trumpet and saxophonists Aubrey Simani, Duku Makasi, Khaya Mahlangu and Teaspoon Ndelu, among many others.

Evolving and flourishing

The house bands continued to change in this way over time. Later, Sundays became exclusively for cabaret and many prominent vocalists flourished. Singers included Count Wellington Judge, Taliep Petersen, Sophia Foster, Mara Louw, Abigail Kubeka, Thandi Klaasen and Sophie Mgcina.

“It was an opportunity to hang around the best musicians in the country,” says guitarist Menyatso Mathole, who jammed at the Pelican every weekend and later joined the Ensemble of Rhythm and Art. “Meeting all these guys for me was the greatest thing ever.”

Mathole maintains that the music was progressive and of a high standard because “it was run by giants”, naming Khoza, Lucky Michaels, Manana and Baba Mokoena.

Drummer Sipho “Hotstix” Mabuse notes that it was a space for musicians to learn and grow to be versatile. He first went there as a teenager while rehearsing with his band The Beaters in a dry-cleaning factory near the venue. He describes it as “a school of music development”.

“Eventually we had so many musicians come that we didn’t have to pay for them because they just wanted to be on that stage,” Leo says.

As disco emerged towards the end of the 1970s, band time was cut down and they were replaced by DJs. “Our very first DJ was my youngest brother Victor Tandy,” he recalls.

There were also visits by American musicians in the early 1980s who came to perform at the Colosseum theatre. “The Pelican was still the only after-hours place that Black performers could go to. We had people like Jimmy Smith, Sarah Vaughn, The Temptations, Della Reeses’ band and Ray Charles’ band,” says Leo.

Band rehearsals took place in the basement. “We used to park there during the break and just listen to stories from the elders or play tunes,” says Mathole. It became a home for musicians who didn’t have anywhere to stay when they came to Joburg.

Former president Kgalema Motlanthe worked as a supervisor of a bottle store across from the railway station in Orlando near the club, and he frequented it in its early days before he was arrested in 1976.

“The Pelican was very important in the sense that it served as a nerve centre for musicians. This was an oasis for those struggling to get jobs, as we’re talking about an era wherein African jazz musicians had very limited opportunities. So it was a space for them to hang out, rehearse and play,” he says.

Defying apartheid

In the 1950s, bottle stores were segregated by race. Black people were limited in what liquor they could buy and “they would often send fair coloureds to buy whiskey and spirits from the white side”, Leo explains. “The Afrikaners were afraid that liquor would make Black people rich and independent, and then make the movement against apartheid stronger.”

Apartheid laws clamped down more severely in later years as pass laws and the restriction on musicians’ movement meant running a music venue was near impossible. It also became illegal for Black venue owners to sell alcohol. The Pelican, however, defied the apartheid authorities’ idea of what joy meant and how it was supposed to be observed.

“We were running an illegal business as far as the government was concerned. Whenever they used to raid the Pelican, they would come with 20 to 30 trucks. We always had somebody looking out for them at the entrance to let us know they’re coming.”

Lucky was instrumental in changing the laws around liquor sales and licences as the chairperson of both the Soweto Tavern Association and later the National Taverners Association. As a result of their work, taverns in the townships were born and licences started being issued to Black venue owners for the first time.

“So, we ended up having the first of those licences, which then made the Pelican legal for the very first time. That was around 1984,” says Leo. With liquor licences now available to Black people, more clubs started to emerge. The Pelican lost clientele to a new glitzy club called New York City situated opposite the Oriental Plaza in Fordsburg.

The Pelican eventuary shut its doors in 1986. “It was a very tough year. There were student riots, boycotts and big marches. But crime also took a different turn as people had access to AK-47s and started going into shebeens, robbing people and shooting people in trains.” After an armed incident, Leo decided to close the venue. He moved on to running a bottle store, while Lucky invested in a cigarette wholesaler business. He died in 2004.

A legacy of joy

For over a decade, Matsuli Music researched ways to centre an album release around the memory of the Pelican. It took some time to get the right tracks and licensing in place, but it all finally came together in 2021. Three songs by different bands – Pelican Fantasy, Night in Pelican and Pelican City – pay tribute to the venue directly.

“I’ve listened to the album, and it just indicates to me that this was a different period altogether,” Motlanthe comments. The album does not focus on the club’s early jazz years, but rather most of its tracks are upbeat, dance- and groove-oriented. It is an impeccably curated compilation and stands as a documentation of Black joy under apartheid.

“The Pelican is a space that happened during the most difficult time of South Africa’s people in the township,” Mabuse says. Its story reveals that different races mixed even at the height of apartheid, that ways around the laws of the time were found and that music thrived in the under-represented 1970s.

There are hundreds of musicians who have been left out of the Pelican story. Not much can be found about Lucky Michaels. Very few photographs of the venue exist. Its story has yet to be written into the history books.

“When it closed down, it was a sad thing. One of the most important institutions in Soweto! Until today, there’s never been anything like that, and I don’t think there will ever be anything like that,” laments Mathole.

Without its stories, no one would learn about how its youngest performer was Lebo M at age 13, or how Radio Bop presenter and vocalist Edgar Dikgole became the “Barry White” of Soweto, nor the tale of how it launched the career of popular trio Joy.

Research into the club’s history shows that the Pelican’s reputation was so great and its impact so huge for people that many have created (fabricated) memories about it … a sign of importance for the myth it became.

As Manana notes: “It wasn’t a place for scrutiny. It was only a place for enjoyment. People just wanted to enjoy themselves.”