The meaning of Ajax Amsterdam

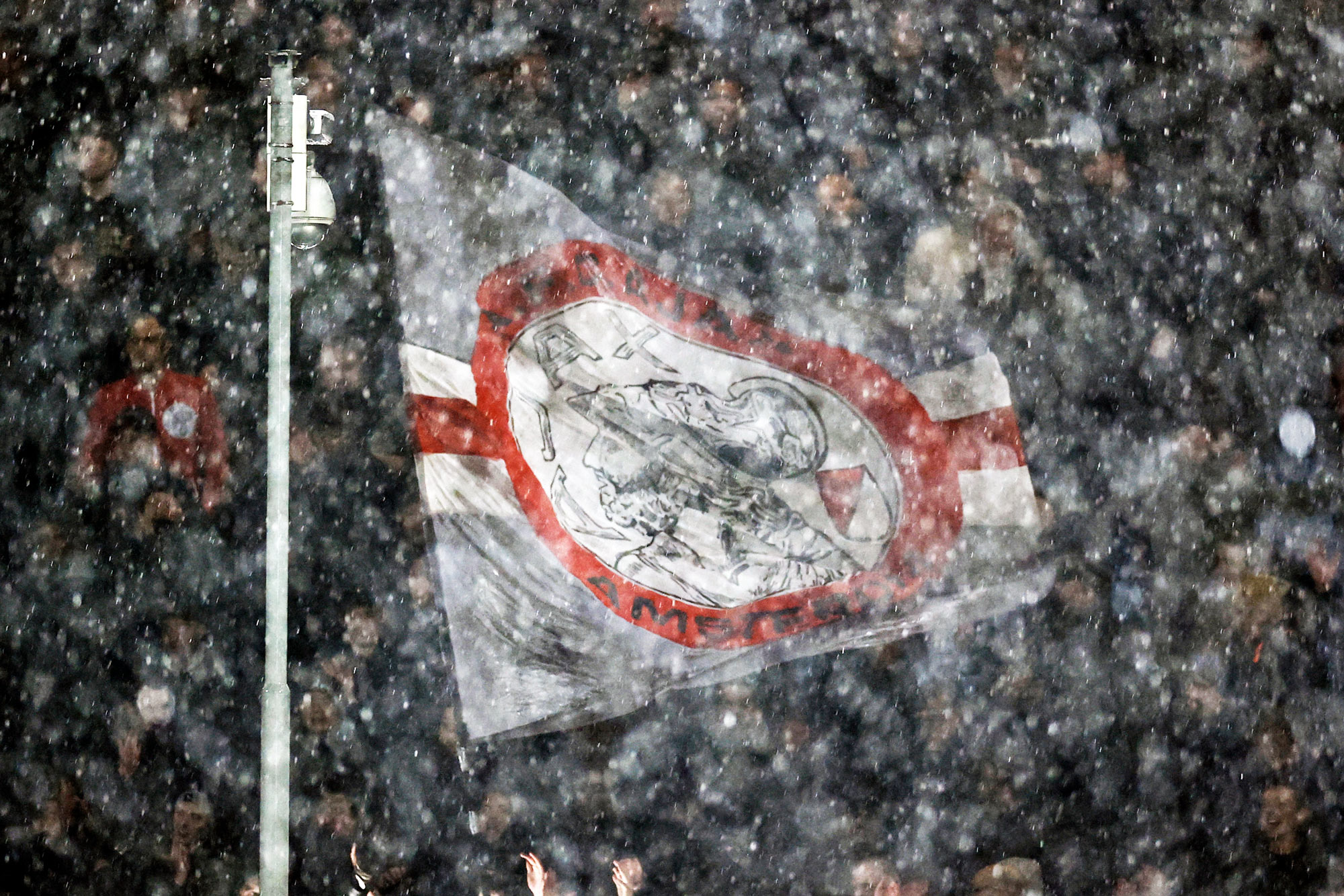

The club and the city are inextricably intertwined and both are emblems of something far more than the riveting action on the pitch that football fans the world over embrace and admire.

Author:

23 February 2022

Some football clubs are more than just a club. Fuelled by their own self-aggrandising mythology and burgeoning trophy cabinets, they command our attention no matter their current log standing or our own allegiances. They play in cathedrals, fortresses and theatres of dreams. Support them and you’ll never walk alone.

Ajax Amsterdam are in this special group. With 35 league titles, 29 domestic cups and 12 continental and international trophies, including four Uefa Champions League triumphs, they are the most successful club in Dutch football. All are on display and available to see on the Ajax stadium tour. All except one.

Last year, after lifting their 35th Eredivisie cup, the club melted it down and made 42 000 silver stars to give to season ticket holders. This was a show of thanks to those loyal supporters who were denied the chance to lend their voice to another successful campaign because of the Covid pandemic.

It is a large number of trinkets, but you could likely find many more than 42 000 people who claim to own one of them. At the Cafe Emmelot bar in central Amsterdam, five people profess to each have one. That they’re drinking in a pub, rather than using their season tickets to watch a home match against league rivals PSV Eindhoven, raises suspicion. But most of the group are adorned with Ajax tattoos and speak glowingly of the club as one would of a beloved relative, so perhaps they’re telling the truth.

“We’re all children of this club, and the club is a child of this city. We are part of the history,” says Julian Kluivert, a lifelong supporter in his mid-30s. He is wearing the team’s third kit – three stripes in red, yellow and green against a black shirt, a nod to the Jamaican singer Bob Marley and his song Three Little Birds, which has become an Ajax anthem. “Supporting this club gives us something unique that other football fans in Holland don’t have.”

That’s a big claim. Any ardent follower of another team would take issue with this statement. And yet Ajax fans routinely make such proclamations. One inside the Cafe Emmelot says he is a member of the F-Side, a hooligan group once infamous for brawls with rival fans, and also takes responsibility for setting off fireworks outside Real Madrid’s hotel the night before a Champions League game in Amsterdam in 2019. Another fan on the stadium tour claims to have played in Ajax’s famed youth academy, though he declines to share his name to verify this.

“Sometimes we want to be connected more than we are,” says Kluivert as Ajax hammer PSV 5-0, though he supports his connection to the club with photographic evidence. His uncle Patrick scored 70 goals for Ajax, including the 85th-minute winner against AC Milan in the 1995 Champions League final. His cousin Justin now plays for Nice in France after graduating from the Ajax academy. To prove his legitimacy, he opens his phone and produces a selfie of the three of them at a recent family gathering.

A product of place

Discerning fact from fiction is difficult when exploring the relationship between Ajax and their fans. There is the degree of arrogance found in any successful sporting organisation, but with Ajax this is also closely linked with the city itself.

“It’s a special place and there is no denying people are super proud of it,” explains Daniel Bar Sharabani, who was born in Amsterdam but has spent the past 20 years in Tel Aviv, Israel, where he co-founded the I-Side Ajax fan group. “It’s a city that evokes meaning everywhere you look. The canals, the museums, the little restaurants, the rivers. It’s beautiful. And Ajax and Amsterdam are the same thing. When you say one, you have to say the other.”

Cycling through the city’s pristine bike lanes, it’s hard to disagree. It is unquestionably a beautiful place. Its concentric canals drip with history. And yet, like everywhere else in the world, it is a place laced with hypocrisy.

Related article:

Take Ajax’s spaceship-like home, the Johan Cruyff Arena, named after the club’s most iconic player who galvanised them to three consecutive European Cup wins between 1971 and 1973. Cruyff transformed the sport, along with coach Rinus Michels, with the philosophy known as Total Football. This new way of playing encouraged every member on the field to take ownership of the ball when in possession and press hard without it.

After his first foray into management with his hometown club, Cruyff went to Barcelona, where he set up La Masia, a youth talent factory that produced all-time greats such as Pep Guardiola, Xavi Hernandez, Andrés Iniesta, Gerrard Piqué and Lionel Messi. Some of these graduates are now coaches themselves, spreading Cruyff’s gospel to a new generation of disciples.

The 55 500-capacity stadium is located south of the city in a densely populated area known as the Bijlmermeer. The area has few shops or restaurants and is bereft of any of the old-world charm found further north. Its high-rise concrete flats are brutal by comparison and house a population of over 50 000 people representing a reported 150 nationalities. The majority are migrants or the children of migrants from Morocco, Turkey and Suriname, a former Dutch colony and the birthplace of Ajax legends Clarence Seedorf, Edgar Davids and Stanley Menzo.

Spurned by the ‘real Dutch’

“The only reason anyone goes [to the Bijlmermeer] is because of Ajax,” wrote the British author and journalist Simon Kuper in his 2003 book, Ajax, the Dutch, the War. The far-right Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn, who was assassinated in 2002, may have had a point when he said “the Netherlands is a country of apartheid”.

“I don’t like going there,” says an older fan the night before the PSV game at the Ruk & Pluk bar on the western edge of the city centre. He asks not to be named, but only after he realises his words are being recorded. “It’s not what it used to be. It was much better when the stadium was in a better place,” he says, referring to the De Meer stadium further north that closed in 1996. “I think those people who live around the new stadium aren’t really Dutch.”

His drinking companion, carpenter Hendrik Visser, 63, who has lived in Amsterdam all his life, slaps him lightly on the shoulder. “You can’t say that,” he says. The bartender and another patron laugh, unperturbed by the man’s overt racism.

Outside, Visser is happy to speak while enjoying a cigarette and asks for forgiveness on behalf of his friend. “There is racism in all of the Netherlands,” he says through a translator, referencing the hyper-nationalist Party for Freedom and its leader, Geert Wilders, which won 10.8% of the vote in last year’s elections on an anti-immigration ticket. “But we like to believe that Amsterdam is different. My friend is originally from Rotterdam. They can be like that. We’re more tolerant of others over here.”

This assumption is challenged in Kuper’s book, which positions Ajax as the club that attracted the country’s educated, liberal middle class. Amsterdam was the epicentre of the Dutch Golden Age of painting that gave rise to Rembrandt, Jan Vermeer and Jan van Goyen. Vincent van Gogh might not have spent much of his 37 years in the capital, but his works are on display at the world-famous museum named after him.

The University of Amsterdam is ranked among the top 100 universities in the world and not one resident of the capital had a bad word to say about their “Venice of the North”. Supporting the football club synonymous with the city has long been a clear proclamation of one’s idealised image of their own world view.

Questionable narrative

And then there is Anne Frank, the young Jewish girl who wrote a diary while hiding with her family from the Nazis. Translated into 67 languages, more than 30 million copies have been sold. “Anne Frank is part of Amsterdam’s undying glory,” Kuper wrote. She is a symbol of the Dutch resistance narrative that has been warped into something only vaguely resembling the truth.

Amsterdam lost 80% of its Jewish population in World War II. Many, the Franks among them, were betrayed by their neighbours. Only Germany had more enthusiastic support for Adolf Hitler’s twisted cause as the Nationalist Socialist Movement in the Netherlands could count more than 100 000 members in 1944.

It’s true that Amsterdam’s February strike of 1941, a year after German occupation, was ignited in defence of persecuted Dutch Jews. We also know that Ajax fans booed a swastika flag when it was flown above their stadium for the visit of an Austrian team already under the yoke of Nazi rule. But these are exceptions. As Hanns Albin Rauter, the senior German police officer in Amsterdam, wrote to the Holocaust architect Heinrich Himmler in September 1942: “Concerning the ‘Jewish Question’, the Dutch police behave outstandingly and catch hundreds of Jews, day and night.” Other small occupied nations such as Bulgaria and Denmark famously resisted. After Rotterdam was bombed, Dutch people seemed more than happy to oust their Jewish compatriots.

Related article:

Football was not exempt from this evil. “Ajax was stuffed with collaborators,” Kuper pointed out, rubbishing the well-worn assertion that “Holland was better than the rest” of occupied Europe. And yet this fable gained a foothold and calcified into an ingrained belief that Ajax, in particular, were a bastion of Jewish resistance.

In the 1960s rival fans began labelling Ajax a “Jewish club”. Ajax players, Cruyff among them, were mistakenly thought to be Jewish. And as football hooliganism arrived in the Netherlands in the 1970s after gaining traction in England and Italy, supporters of other teams started chanting antisemitic songs and brandishing swastikas in the away end of Ajax’s stadium.

Rather than shrink away, Ajax embraced this. Fans adopted the Jewish Star of David and the Israeli flag as symbols of the club. The atrocities committed during the war by Dutch people became lost in football tribalism. Feyenoord fans would sing “Whoever doesn’t jump is a Jew” as a means of creating an atmosphere, while Ajax supporters could download the Jewish folk song Hava Nagila as a ringtone to prove their loyalty.

“This connection is not why I support Ajax, but I know many Israeli fans are attracted to this,” Bar Sharabani says. “The club doesn’t try to make it a big deal. But the history is there. Ajax transcends football. It’s bigger than what anyone tries to say it is. It means so many things.”

Mad for the club

One could make the case that Ajax are the Netherlands’ most significant cultural export. Watching football is the world’s most popular pastime, uniting more people across race, class and geographic boundaries than any other shared experience. More than tulips and bicycles and liberal laws, more than artists and museums and coffee shops selling products that get you high, it is this football club and their heroes that best embody the spirit of the city.

“It’s why I’ve spent so much money going there every chance I get,” says Bradley Dobson, a season ticket holder who lives in Halifax, northwest England, and attends up to 19 home games a season. “My friends and family think I’m mad, but I wouldn’t take any of that money back.”

Dobson first fell for the red and white of Ajax after his aunt took a job in Amsterdam. It was the club’s almost fanatical promotion of youth that piqued his interest, but it was the majesty and mythology that got him hooked. He cried in the stands when Tottenham Hotspur beat Ajax at the death in the 2019 Champions League semifinal. He was stunned into horrified silence at a 2017 preseason game in Vienna when 20-year-old academy prospect Abdelhak Nouri collapsed on the field after sustaining a cardiac arrest that left him with permanent brain damage. Dobson has Nouri’s image tattooed on his forearm.

“This club is special,” Dobson says. “I’ve travelled all over Europe and watched many teams, but the Ajax supporters are on another level. They’re friendly and welcoming and passionate all at once. I’ve been made to feel at home. I can’t quite describe what it means to me.”

Perhaps he doesn’t need to describe it. Perhaps there is no accurate way to encapsulate the meaning of this club to the city that is adorned with Cruyff’s image and the No. 14 that he wore during his pomp. Perhaps meaning is irrelevant when watching a team with a wage bill smaller than Premier League teams Crystal Palace and West Ham United compete against the best sides on the continent, while producing future household names on an annual basis.

Perhaps mystery is to be expected when analysing a club named after one of the mythological figures of the Trojan War. Who needs concrete facts when there’s a good story to tell? And if that is unsatisfactory, then you might want to take it up with the spirit of Cruyff, who once said: “If I wanted you to understand, I would have explained it better.”