The Mandela House museum mess

Nelson Mandela’s former home on Vilakazi Street is in liquidation, drawing harsh criticism from Soweto Tourism and the sidelined trustees of the original Soweto Heritage Trust.

Author:

20 April 2021

A reportedly dysfunctional trust and a high turnover of managers, some said to have lacked vision, have been stated as the reasons why the iconic Mandela House museum in Orlando West, Soweto, finds itself in a desperate state.

The Soweto Heritage Trust, for which the Apartheid Musuem manages Mandela House, is said to be dysfunctional and without an active board of trustees. The heritage trust came under harsh criticism when it was revealed that the museum has been liquidated. A tender was advertised for interested partners who are willing to take over running the house on 8115 Vilakazi Street. It has been reported that the museum is in debt and its assets may be sold to pay debtors.

The museum is under the control of joint liquidators Allan Pellow of Mazars Recovery and Restructuring and Michael Moloto of Bahlanka Business Solutions and Administrators, which the Johannesburg high court appointed in 2017. In the advert, the liquidators say their decision-making is about “the preservation of the integrity of Mandela House as an important South African heritage asset and to ensure any change in ownership is properly managed and mitigated, and its cultural significance is conserved and managed sustainably”.

Nelson Mandela sold the house to the non-profit Soweto Heritage Company in 1998, the liquidators said in November 2020. The company was established to aid the Soweto Heritage Trust’s main objective of creating a cultural precinct in and around Soweto with Mandela House as its principal asset.

“The affairs of the company and the trust were inextricably linked, both sharing a common purpose, and were intended to operate in a symbiotic manner. The trust, like the company, was rudderless and unable to function effectively in the absence [of] a quorate board of trustees,” said the liquidators.

The Apartheid Museum has run the museum since 2010 and “neither the [Mandela House] museum nor its contents will be sold to defray any expenses or costs that have or will be incurred in the running thereof”, they said.

Trustee response

Soweto Tourism is against the liquidation and has vowed to intervene and find a way to save the museum. It has initiated several virtual round-table meetings with the trustees: Standard Bank, the Gauteng government, the Johannesburg metro municipality (which Soweto Tourism accuses of being responsible for the liquidation) and Busiswa Gcadinja (a former Gauteng government employee whom it accuses of applying for the liquidation).

Gcadinja’s lawyers declined the invitation for a meeting on 15 February, saying the matter was still before the judge. And during the meeting, no one wanted to shoulder the blame for the situation.

“We have then submitted a turnaround strategy to the trustees and applicant to withdraw the liquidation application for the court and explore a new governance structure that is inclusive of the museum staff, community and local tourism development practitioners to fast-track implementation of the trust objectives,” said Soweto Tourism.

Standard Bank said it had done all it could to prevent the situation at the museum, saying that despite its “best efforts over some years, we were unable to secure the attendance of the various directors at company meetings or obtain instructions from them on the way forward”.

City of Johannesburg spokesperson Nthatisi Modingoane said: “Issues concerning the future of the Mandela House are being addressed by a government task group, including senior representatives from the heritage and tourism sectors, and is championed by the Gauteng provincial government.” He added that the initiative is aimed at ensuring the museum is preserved, placed on a proper footing and operated as a site of national importance.

Attempts to get a response from Gcadinja were unsuccessful.

The state of Mandela House

Businesses in famous Vilakazi Street, where the museum is situated, are slowly recovering from the financial devastation wrought by Covid-19. “I’ve been working here at the Mandela Museum since 2010. At first, I was an intern. I found a gap in the photographing souvenir industry. We issue out souvenirs that get done in eight minutes to customers,” said 32-year-old Mduduzi Tshabalala.

Tshabalala sits at the entrance to the museum with an A4-sized, framed photo collage to entice visitors. He has three assistants in his employ, but with few visitors his business has been affected severely. “Business was so busy, we could not even manage to do proper administration. Covid-19 has wrecked us and we are now not as busy as we used to be,” he said.

The modest, four-roomed house was restored in 2008 and reopened to visitors the following year as a national monument. It still has its apartheid architectural look and feel. Tour guide Arabile Monakwane shared the house’s historical significance during a visit. Mandela bought it as the marital home with his first wife, Evelyn Ntoko Mase, who was a nurse. The pair divorced in 1957 and Mandela married Winnie Madikizela the following year.

In the front yard stands a tree that Mandela planted. It is said that’s where he buried the umbilical cords of his children and grandchildren. “During apartheid, this house was put on fire twice during the Stompie issue and by the police,” said Monakwane. “So most of their things were destroyed in the process.” She added that the “line here on the ground between the kitchen and lounge, [where] Winnie had built a wall as protection to avoid the shootings from the police, the wall was removed during the renovations.”

The new round, thick and rusted steel fence surrounding the house represents prison bars. The Soweto Journal online magazine has reported that the museum receives around 350 people a day in peak seasons and about 200 in off-peak times. Schoolchildren are charged an entry fee of R20, locals R40 and international tourists R60.

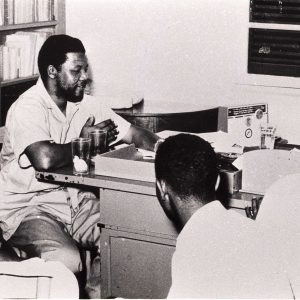

Shadrack Motau, who claims to have been part of the original Soweto Heritage Trust, recalled spending time with Mandela’s son Makgatho when he used to live in the house with his wife. “Winnie had already moved out of the house. We were very close to Makgatho Mandela. We used to drink beers at John Morgan’s place, who was a driver for Winnie,” he said laughing.

The ‘forgotten trustees’

Motau helped the museum find people who knew Mandela before he was arrested, to speak on camera about the late president. Their testimonies are shown to museum visitors. “I never benefitted anything, I was not paid [for that],” he says. It’s not the only thing about which he feels hard done by when it comes to those who run the museum.

Two signs greet you at the main entrance to Mandela House. The top sign says the museum was opened in 2009 by then Gauteng premier Paul Mashatile and Standard Bank South Africa chief executive Simphiwe Tshabalala. The second sign says the museum has been managed by the Soweto Heritage Trust, whose members include Mandela and activist and doctor Nthato Harrison Motlana.

Related article:

“Mandela and Dr Motlana were never involved in the trust,” said Motau. The 76-year-old said he, Sydney Phuti, David Moshapalo and Victor Modise were the original Soweto Heritage Trust members. “We were appointed as trustees in 1996,” he said at his home close to the museum. “We were nominated because of our contribution to the communities.”

He went on to say that during apartheid and into the democratic dispensation, he worked closely with ANC heavyweights like Joe Matthews (Naledi Pandor’s father), Thomas Manthata and the Soweto Civic Association under the leadership of Motlana and Isaac Mogase.

Motau, Phuti, Modise and Moshapalo were political activists in Soweto. Their task as trustees was to look after the interests of the Mandela House museum, as well as the Hector Pieterson Museum, the Apartheid Museum and the Iziko Museum in Cape Town. But it seems that the agreement was only communicated verbally between the parties as there were no signed contracts that stipulated their roles, responsibilities and remuneration. “I didn’t know the logistics and benefits of the trustees,” said Motau.

Sidelined by the bank

Standard Bank initiated a trip to the United States for the four trustees, along with architect Phill Mashabane of Mashabane Rose Associates, in 1998. “We were treated like VIPs,” said Motau.

Their mission was to research and learn how museums are operated and presented, and about the preservation of history, heritage and legacy. Mashabane’s goal was to find out what creative designs would be suitable for each project. “We were there for almost two weeks and we visited the Martin Luther King Museum in Atlanta, Georgia. When we got there, they were busy building a bigger museum,” said Motau.

They went to Boston, Massachusetts, to see more museums and eventually they visited the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC. After returning and sharing what they had learnt, they never heard back from the bank.

Related article:

Motau cannot explain exactly what transpired after their trip. He also doesn’t know why the public is unaware of their existence as trustees. “We were sidelined and we didn’t know why. We tried to enquire but there was no response,” he said.

Months after their overseas trip, the projects started. Mashabane Rose Associates got to build the four museums. After several attempts to get hold of the architect, Mashabane eventually responded with a brief text message, “Yes they did”, confirming that the trip took place and that the four trustees indeed existed.

Standard Bank Master’s Office records dated 20 October 1997 acknowledge all of them except Modise as the original trustees of the Soweto Heritage Trust. The bank did not want to comment further about the trip or what happened after they returned. “We have no information regarding your other queries,” said bank spokesperson Ross Linstrom.

The trustees have gone their separate ways since then and hardly keep in touch. “When we came back, I got involved with Vukani Litlabile Tours Safari to continue with my life,” said Motau.

Despite everything that has transpired, Motau has fond memories of the house and hopes the legacy of the museum will be protected and preserved for generations to come. If not, it “would be a travesty to not just the province but nation”, as Gauteng member of the executive council for culture Mbali Hlophe has said.