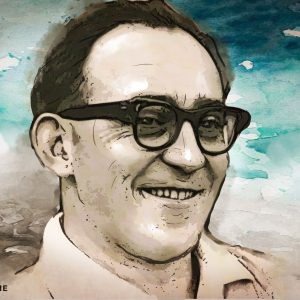

The life and quiet integrity of Andrew Mlangeni

The death of the last Rivonia Trialist marks the end of a generation so committed to democracy and freedom that they sacrificed watching their children grow up.

Author:

23 July 2020

After the death in April of Denis Goldberg, Andrew Mlangeni, 95, was the last living link to the Rivonia Trial, a moment in South African history when liberation leaders were sentenced to life imprisonment. Their names became illicit and images of them were illegal. But their presence in Robben Island and Pretoria Central prisons were unifying symbols of a democratic future.

In the years since the deaths of Nelson Mandela, Ahmed Kathrada and Goldberg, Mlangeni was pushed forward into the spotlight from the self-described “backroom boy” position he had always been more comfortable occupying.

On 22 July 2020, Mlangeni died.

The early years

Andrew Moeti Mokete Mlangeni was born on 6 June 1925 on a farm near Bethlehem in the Free State. He was one of 10 children in a family with two sets of twins, including Mlangeni and his sister Emma. His father, Matia, was a tenant labourer, working on land his family had been dispossessed of by the iniquitous Native Land Act of 1913. He died when Andrew was six. Mlangeni’s mother, Aletta, in keeping with the traditions of the Mlangeni clan, married her husband’s brother, with whom she had a further set of twins.

Mlangeni spent his formative years in the nearby town of Kroonstad, beginning school at 11. He was introduced, through a part-time job as a caddy, to his lifetime love of golf, continuing to play well into his 90s.

Andrew and Emma arrived in Johannesburg in 1940, where he attended St Peter’s Secondary School in Rosettenville. There, he was taught maths and science by future ANC leader Oliver Tambo. In Johannesburg, he became politically aware and active. He joined the Young Communist League of the then Communist Party in 1945, where he was part of a cell led by journalist and activist Ruth First. He devoured the writings of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin. But by the time the Communist Party was banned in 1950, Mlangeni was no longer an active member, having met and married June Ledwaba with whom he had four children.

He supported his family for 10 years with a job making blue-print duplicates for a Johannesburg engineering firm. As he recalled to journalist Pippa Green, he was, in apartheid era terms, “a highly paid black man, earning a monthly salary of 3 pounds, 4 shillings and 8 pence”. With this money, Mlangeni purchased the house in Dube, Soweto, he would occupy for the rest of his life.

Related article:

Mlangeni helped the anti-apartheid movement during the defiance campaign, using the equipment at his employer’s office on Saturdays to make copies of ANC leaflets. After being fired from his job at the engineering firm, Mlangeni worked as a Putco bus driver and returned to active political work. He became involved with the ANC Youth League and joined the renamed South African Communist Party in 1953.

Mlangeni was introduced to Nelson Mandela on a Soweto train platform in 1952. He would become close to the lawyer who was making a name for himself in the ANC. Mlangeni described being “a backroom boy … The police did not know much about me. I did not want to hold positions in the organisations but I helped those who wanted to become leaders … I worked for them … made sure they got elected, and they were the people who got arrested ultimately”. Consequently, while he knew and worked with many of those arrested and tried for treason in 1956, Mlangeni was not among them.

As political activity increasingly became part of his life, Mlangeni’s family became used to his absence. In an interview for a documentary about her father, his daughter Sylvia recalled that “he wasn’t around much. It was difficult but that’s how it was and we accepted it.” They did not know yet how much absence would form part of their family life in the decades to come.

Military recruitment

When the ANC adopted the armed struggle after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960, Mlangeni became one of the first activists Mandela recruited for its military wing Umkhonto weSizwe (MK). “On Robben Island, Madiba would always say that I was the first person he had recruited into MK,” he recalled. “I wasn’t sure if that was true, but I wasn’t going to disagree with Madiba.”

At an ANC safe house in 1961, Mandela informed Mlangeni that he would be leaving the country to obtain military training in China. Together with five other recruits – including Raymond Mhlaba and Joe Qabi – he made his way first to Botswana and from there via Tanzania, Sudan, Ghana, Zurich, Prague, Moscow and Irkutsk to China in late 1961. The recruits were trained in communications and bomb making. Mlangeni recalled how the group had two meetings with Chinese leader Mao Zedong, who “was disappointed that only six of us had been sent for training and told us that we should be sending thousands”.

Related article:

Upon his return home in 1962, Mlangeni became a member of the MK high command. He travelled all over the country disguised as a priest, enlisting and training new recruits in the techniques learned in China. Mlangeni was tireless. Goldberg once commented: “In the liberation movement they called him ‘The Robot’ – it sums up his personality – you’d put the switch on and say, ‘Go!’ and he just kept going and nothing would make him stop.”

Returning home late on the night of 24 June 1963, Mlangeni was arrested together with his Soweto neighbour and fellow MK member Elias Motsoaledi. They were initially tried for intending to smuggle a group of ANC recruits across the border from Zeerust. Although acquitted, they were immediately rearrested under the 90-day detention law and charged together with Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Ahmed Kathrada, Goldberg and others at the Rivonia Trial.

On Robben Island

During the trial, alongside their lawyers, Mlangeni and Motsoaledi thought they would face sentences of 12 years. While surprised when they were handed down life sentences, Mlangeni felt “we were not going to die in prison. The pressure from the international community and the activities of our people in the country and the fact that MK continued with its activities gave us strength.” In his statement to the court during the trial, Mlangeni was adamant: “What I did was not for myself but for my people.”

On Robben Island, Mlangeni became prisoner 467/64 occupying cell number 5, two doors down from Mandela. Although Mlangeni would always say that his sentence was a sacrifice willingly made for the sake of his beliefs, and that it was not as great as those who died in the service of the struggle, he regretted its effect on his family. “By 1964 I had four children. The oldest was a teenager. The youngest was eight years old. What was most difficult for me was not to see my children grow up.”

His wife, June, who was also politically active, was constantly harassed by the security police. They would intervene “every time she got a job”, Mlangeni recalled. “They would go to her employer and say, ‘You have employed the wife of a terrorist, a murderer, a rapist,’ … Employers were scared and she would be fired without reason.”

Related article:

Eventually June was assisted by the South African Council of Churches, for whom she worked until her husband’s release in 1989. Mlangeni did not see his daughters Sylvia and Maureen until 1974, when they “were already women and had their own children”.

In March 1982, Mlangeni and his fellow ANC members were transferred to Pollsmoor Prison, where the PW Botha government approached Mandela with the offer of early release for his fellow prisoners. It would take seven years of negotiations before it was finally agreed that Mlangeni and the other political prisoners would be released in late 1989, with Mandela set to walk free a few months later.

In September 1989, a few weeks before his release, Mlangeni’s twin sister, Emma, died and his permission to attend her funeral was denied. He told Green, “I cried more than I cried for all the other deaths. I felt that part of me had died, that my other half had died, that I was no longer myself.”

Returning home

In the early morning of 15 October 1989, Mlangeni stood outside the Dube house. His family, exhausted after not hearing any news since the announcement of his release, were asleep. Mlangeni picked up a handful of pebbles and threw them against the roof, eventually waking Sylvia. Coming outside to investigate, she was greeted by the sight of the father she had not been able to touch for 25 years.

After an emotional reunion, Mlangeni immediately returned to political life. Alongside other released prisoners, he made public appearances calling for a re-evaluation of the popular slogan “liberation before education”, emphasising the importance of education for the impending democratic transition. Mlangeni had been the first prisoner to register for a BA degree when access to education was granted to Robben Island inmates in 1968. It took him 12 years to obtain his qualification and upon his release he had been in the process of completing a law degree. In 2018, he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by the university currently known as Rhodes University, where he made a speech quoting Marcus Garvey: “Liberate the minds of men, and ultimately you will liberate the bodies of men.”

A commitment to integrity

Mlangeni served as an ANC MP from 1994 to 1999 and again from 2009 to 2014. He was also co-chair of the ANC’s Integrity Commission, where he endeavoured unsuccessfully to lobby former president Jacob Zuma to step down in the face of allegations of corruption and capture by the Gupta family. In 2016, the committee “invited Zuma to a meeting and asked him to step down quietly. We thought we could talk to him privately, praise what he had done in the past and nicely ask him to step down.” It took another two years for Zuma to resign. Mlangeni placed his commitment to the good of the country above loyalty to party leaders.

Mlangeni’s son Aubrey died in 1998 and June died of cancer in 2001. Mlangeni was always grateful for the sacrifices and struggles his wife endured to keep their family together during his imprisonment. He said, “If only God had allowed me more time to make her happy.”

Towards the end of his life, Mlangeni was still concerned that there remained much to achieve. He expressed the urgency of seeing “the country peaceful, corruption destroyed, the economy improving, jobs being created, houses being built, electricity and water supplied”.

Mlangeni believed that participation in the struggle did not entitle anyone to favourable treatment or unearned rewards. With his passing, and the end of any tangible link to the Rivonia generation, Mlangeni’s life and ideals will hopefully continue to stand. President Cyril Ramaphosa noted, in his official statement, that Mlangeni’s passing marks “the end of a generational history [that] places our future squarely in our hands”.