The legacy and significance of Mmabatho Stadium

The structure, now close to becoming a white elephant, is a metaphor for the Bantustan it was meant to prop up. It was always doomed to fail.

Author:

10 December 2021

Like many revered Bophuthatswana projects, Mmabatho Stadium is often thought of as Lucas Mangope’s love letter to his people. But when Israeli architect Israel Goodovitch and engineer Ben Abraham sat down to design the stadium, they were thinking of a monument to a king, not an accessible public facility. The stands feature elevated platforms that give the stadium a shape of something from a science-fiction film.

Many building and event experts have long argued that Mmabatho Stadium is not viable as a public facility. That message was hammered home in 2010, two decades after it was built. Not only was it snubbed by Fifa as a venue for the first World Cup on African soil, but it was also not good enough to be a training venue for the global showpiece that pitted 32 of the world’s best teams.

Goodovitch and Abraham’s involvement highlights just how invested Israel was in the possible success of Bophuthatswana, one of apartheid South Africa’s Bantustans. Another Bophuthatswana sector that Israel heavily invested in was agriculture. Israel long had water problems that greatly affected its farming sector, so mitigating its own agricultural instability could have been another rationale for its investments in Bophuthatswana, which exceeded $40 million at some point.

To gain legitimacy with other states, or on the global stage, South Africa often passed off or presented its semi-autonomous regions (Bantustans) as destinations of investment. Bophuthatswana was one, offering certain “liberties” that South Africa did not have. Israel and the apartheid regime had strong ties that helped strengthen the stronghold they had on the people both these countries oppressed. Though it was resources that attracted states like Israel to Bophuthatswana, there was also the hope that it would one day become a fully independent state and a staunch ally of Israel.

The building of Mmabatho Stadium presented Mangope, who was in firm control of Bophuthatswana at the time, with the biggest challenge of his political career. The building of the stadium was marred by corruption allegations. As the scandal ensued, Mangope’s enemies, led by Malebane Metsing of the Progressive People’s Party (PPP), resolved to overthrow him in 1988. A group of disgruntled Bophuthatswana Defence Force members surrounded Mmabatho Stadium in February, but the rebellion was eventually stamped out by the intervention of the then South African Defence Force. A stadium built in part to symbolise Mangope’s reign became his prison for that brief moment.

To Mangope’s disappointment, the failed coup did not silence the criticism around the construction of the stadium. Instead, questions about the stadium’s funding continued to rage – even long after the PPP was banned. To give the stadium a greater meaning and perhaps to pacify its critics, a regional league was formed, the Bophuthatswana Professional Soccer League, which barely caused a blip in the football landscape. Their only “success” story was former Bafana Bafana captain Lucas Radebe, who started his career there.

Toxic legacies

Another Israeli, former Hapoel Tel Aviv goalkeeper Amatzia Lefkowitz, was roped in to run a coaching school to benefit the league. With a R500 000 annual sponsorship cheque from Sol Kezner’s Sun International, it was a financially rewarding affair.

The involvement of Kezner was not a matter of social responsibility. It was fuelled by the need to keep the Bophuthatswana regime happy. Kezner was one of the many business people who benefited greatly from Mangope’s rule. Many of the activities that Sun International offered, such as gambling, were banned in South Africa, but Bophuthatswana’s semi-autonomous status meant Kerzner could legally operate his businesses there. Such “freedoms” propped up Bantustans and legitimised the despots who ruled them although in reality they were controlled by the Pretoria government.

Today, Mmabatho Stadium enjoys a treatment often reserved for religious symbols, even though it is not used much. Local government has, however, failed to capitalise on the stadium’s popularity to promote it to the public as the multi-purpose centre it could become.

Related article:

This has a lot to do with the stadium’s inaccessibility, another Bophuthatswana legacy. Mahikeng largely remains a divided town – residents of central Mmabatho continue to enjoy many spatially demarcated privileges like access to a 24-hour police station and proximity to learning institutions like the Mmabatho Nursing College and North West University. It is a “privilege” other places in the province do not have.

To put this inaccessibility in context, when the North West University took part in the Varsity Cup, they played at the smaller Montshiwa Stadium. This despite the Mmabatho Stadium being a few kilometres away from where the team trains. The university side is the closest thing to a structured team playing at the highest level in the province. Mmabatho Stadium has not tasted domestic football in a long time, and with no professional club in the North West, and better facilities like Royal Bafokeng Sports Palace and Moruleng Stadium, it is unlikely that the stadium will see competitive football anytime soon.

The stadium is part of the many developments that legitimised the Bantustan system and has, over time, immortalised Mangope. That he is revered and religiously worshiped by some for his foresight is not a mistake; it was by design. This is what he understood when he became prime minister, that long after he’s gone his name would echo through Bophuthatswana infrastructure. For many, his crimes end up being whitewashed when his legacy is discussed.

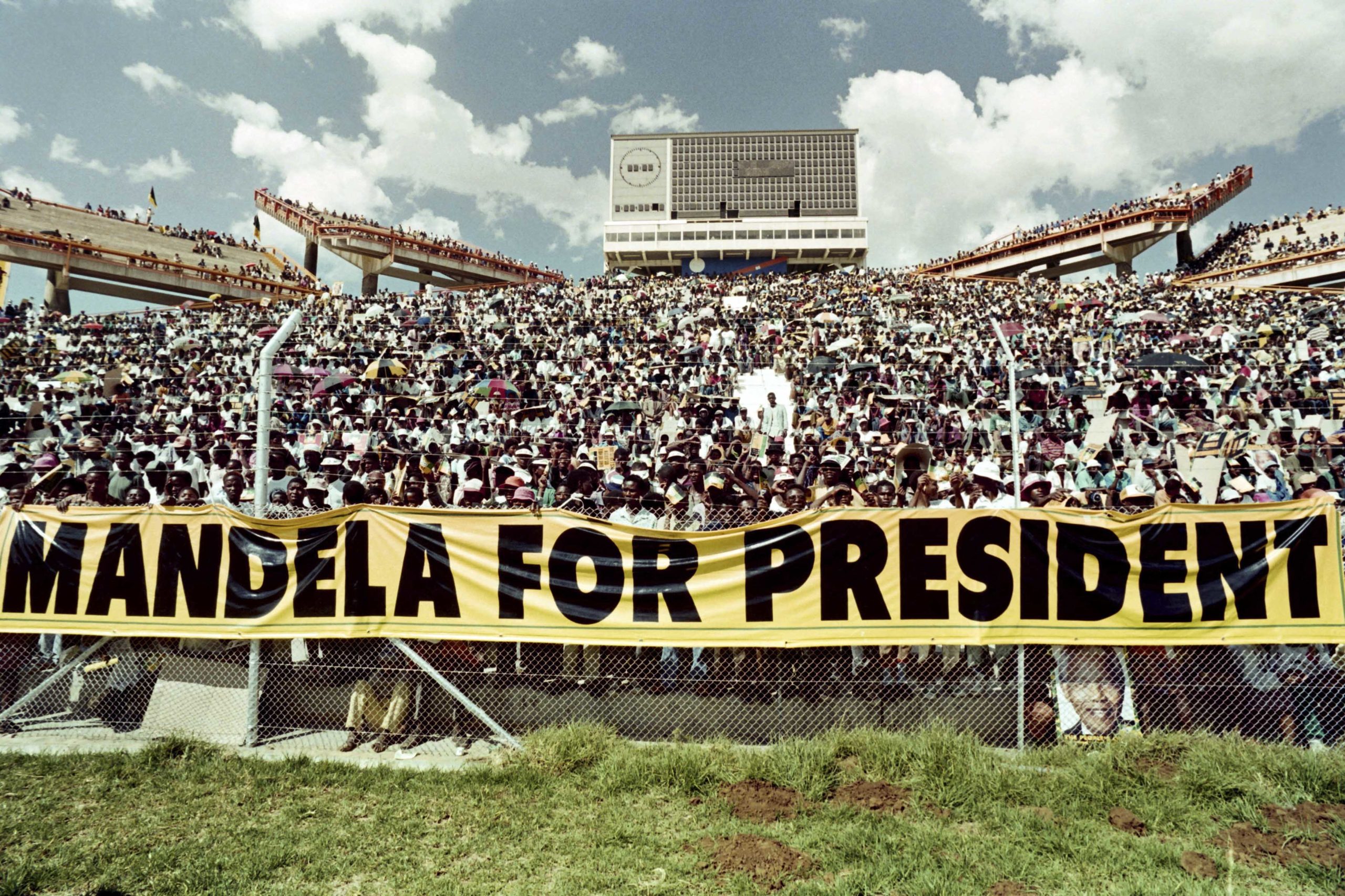

Mangope understood that one day he would have to give it all up and let someone else steer the ship, but he underestimated how fast and violently that moment would come. A sudden demand for democracy turned Mmabatho from a quiet city to a war zone in a day. His announcement that Bophuthatswana would not take part in the 1994 elections may have been rooted in the shock of how fast that moment had come, rather than delusion.

Listening to those who view Mangope as a hero, you would be fooled into thinking he was a socialist revolutionary while he was, in fact, a free-market-capitalist adherent who entrenched and furthered inequalities in Bophuthatswana. This romanticism of the past is a reflection of the disappointments of the present, rather than an acknowledgement of the “success” of Bantustan leaders. Many are feeling let down by democracy. They feel that what former “homelands” had, in terms of infrastructure, was decent.

The paradox of the infrastructure that sets Bophuthatswana apart from much of the country, like Mmabatho Stadium, is that while it is sometimes seen as symbolic of Mangope’s foresight, it is just as much a sign of his failure to see the new order that was rushing towards him.