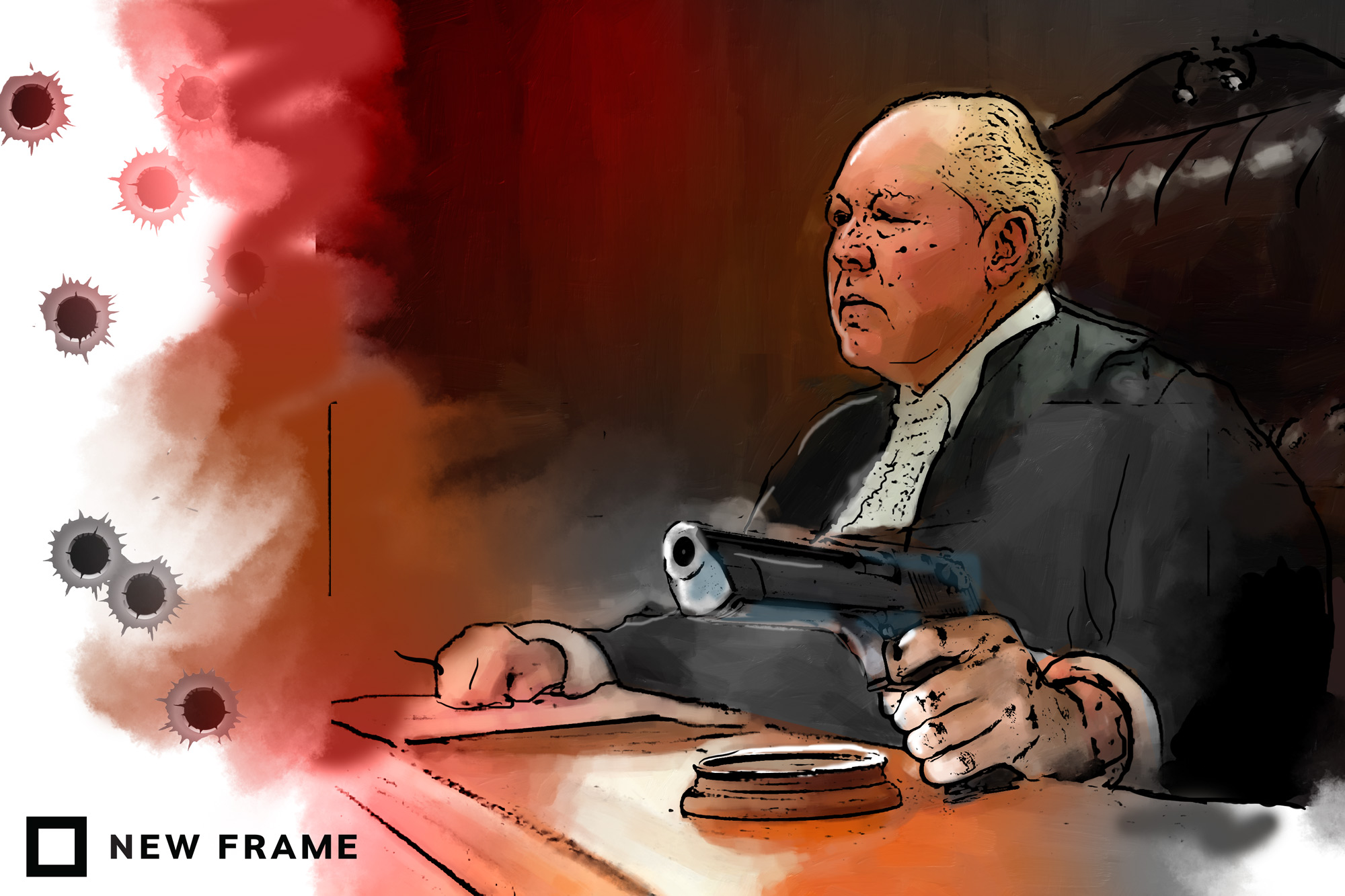

The judge who kept unlicensed guns on our streets

Two years ago, the Constitutional Court confirmed that firearm ownership is a legislated privilege, not a right. But a high court judge stepped in to protect criminal gun owners.

Author:

7 September 2020

Under apartheid, a gun licence lasted for life. But since the Firearms Control Act was passed in 2000, that is no longer the case. Nobody in South Africa has a right to own a gun. Gun ownership is, instead, a privilege regulated by law.

If a person owns a gun, they must be licensed to do so. The gun requires a separate licence. Under the new gun control regime, each of these must be renewed periodically. This final requirement – the renewal of licences – was at the heart of a court battle that ended on 23 July when the Supreme Court of Appeal dismissed an interim interdict against the South African Police Service (SAPS) handed down almost two years earlier by the high court in Pretoria.

Related article:

In 2018, seven weeks after the South African Hunters and Game Conservation Association failed to overturn the new system of gun licensing and renewal in the Constitutional Court, Gun Owners South Africa – an association of about 40 000 members that protects the interests of gun owners in the country – asked the high court to effectively end the new licensing system.

The resulting interdict meant that gun owners whose licences had expired after they failed to renew them no longer had to surrender their firearms to the police. By prohibiting the police from demanding or accepting the surrender of firearms whose licences had expired, the interdict left nearly 450 000 illegal guns in the hands of civilians.

Judicial conduct

While the majority of gun owners – 1.7 million – had renewed their licences under the new legislation, the Constitutional Court decision confirmed that those who hadn’t were, in effect, criminals.

Among the reasons that the renewal and termination of gun licences should be suspended, according to Gun Owners South Africa, were that “the availability of licensed firearms to the public and security companies plays an important role in the stability of the country” and that, if the licensing system remained in place, “the entire country and all its citizens will suffer irreparable harm”.

The appeal court dismissed these claims, among others, as “bald assertions”, “irrelevant” and “groundless”.

Despite failing to challenge the validity of the relevant legislation, the association asked the high court to extend gun licences to the lifetime of their owners. Apart from rewriting the legislation, this would have taken South Africa back to apartheid-era gun control.

Related article:

While Judge Bill Prinsloo accepted the thrust of the association’s argument in the high court – “the bulk of which,” the appeal court later said, “contained hearsay and unsubstantiated assertions” – he intervened during oral argument to suggest what he called “cosmetic changes” to what the association was asking of the court, parts of which Prinsloo acknowledged were legally incompetent.

The judge then guided Gun Owners South Africa by deleting and recrafting sections of the relief it sought. And so the application was decided not according to what the association had asked of the court, but on the basis of new relief proposed by the judge.

Prinsloo has since retired and will, like all judges, receive a salary for the rest of his life. But the appeal court was scathing in its assessment of the high court judge’s conduct. It called Prinsloo’s amendment of the association’s relief “unusual, troubling and regrettable”, saying that judges “would do well to remember that their function is that of a neutral umpire”.

Related article:

Some of Prinsloo’s interventions, said the appeal court, “may render the court susceptible to an accusation of bias” and had weakened “public confidence in the judicial process”.

In the appeals court, the police suggested that Prinsloo’s conduct was part of a broader pattern in which he “prevented the executive from carrying out its statutory functions”. Gun Owners South Africa’s interdict was not the first of Prinsloo’s to be struck down by a higher court for breaching the government’s separation of powers. In 2013, he penned an interdict that prevented the Tshwane municipality from changing its apartheid-era street names. And in another gun-related case in 2009, Prinsloo granted an interim order preserving the validity of gun licences issued under apartheid-era law after an application by the South African Hunters and Game Conservation Association attacked parts of the Firearm Control Act.

Guns in South Africa

SAPS data shows that, while gunshots were the leading cause of South Africa’s violence-related deaths during the 1990s, deaths resulting from guns started to fall off after the gun control regime was changed with the Firearms Control Act. By 2006, more people were being killed by stab wounds than gunshots despite the fact that gunshot wounds are 18 times more lethal. But gun-related deaths have been on the rise again since 2011 as a result, in part, of the “leakage of guns from legal to illegal markets”, according to research by Gun Free South Africa, a non-governmental organisation that appeared as a friend of the appeal court. Guns are once again the leading cause of killings in South Africa, with almost one in every two murders in 2018-2019 committed with a gun.