The inescapable Umm Kulthum

The ubiquitous artist’s politics and sound evolved over the years, pointing to culture’s potential to shape and shift society, memory and identity.

Author:

27 December 2021

For 40 years, every first Thursday of the month, Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum would perform new music live on radio. Sometimes one, or up to three songs would reach listeners across multiple countries on radio stations like Voice of Cairo, Ezaet Umm Kulthum (a radio station dedicated to her), or Voice of the Arabs, which was popular all over the Middle East. People would gather at home to listen, with concerts lasting sometimes up to six hours. “Stories abound of streets and workplaces from Tunisia to Iraq becoming suddenly deserted as millions rushed home to listen,” The Guardian once reported.

Those who witnessed her live performances were sent into a state of tarab – a meditative, trance-like state of pleasure and emotional exchange between audience and performer. Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz once said, “She acted like a preacher who becomes inspired by his congregation… When he sees what reaches them he gives them more of it, he works it, he refines it, he embellishes it.”

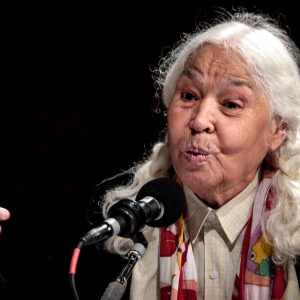

Umm Kulthum defined Arabic music all over North Africa and the Middle East. Perhaps the most famous musician in the region, she became known as the “Star of the East”, “Egypt’s fourth pyramid” and “mother of the Arabs”. Her music spans time and speaks to it too – enduring, evolving with, and dictating mass cultural and political shifts. It is reflective of culture’s deep connection with the world it is located in.

She died in 1973 having spent over half a century making music that would change the landscape of Arabic music, and challenge the position of women in music and in the country in general.

Evolution

In politics and performance, Umm Kulthum was as strategic as she was talented. Having her finger on the pulse, and as she came into her own, she constantly changed her music over the decades, as she changed herself – its style, topic, language and allegiance.

She went from singing grandiose poetry in formal Arabic, performing to elite audiences, to singing populist songs in colloquial Arabic about peasant and working-class conditions in the 1940s. Her use of language reflected this. While she was trained in the recitation of the Qur’an by her father, and had a strong command of the Arabic language and of difficult lyrics, she was still able to sense cultural shifts and move with them, using different composers and her knowledge of common words from her own background to sing popular and relatable songs.

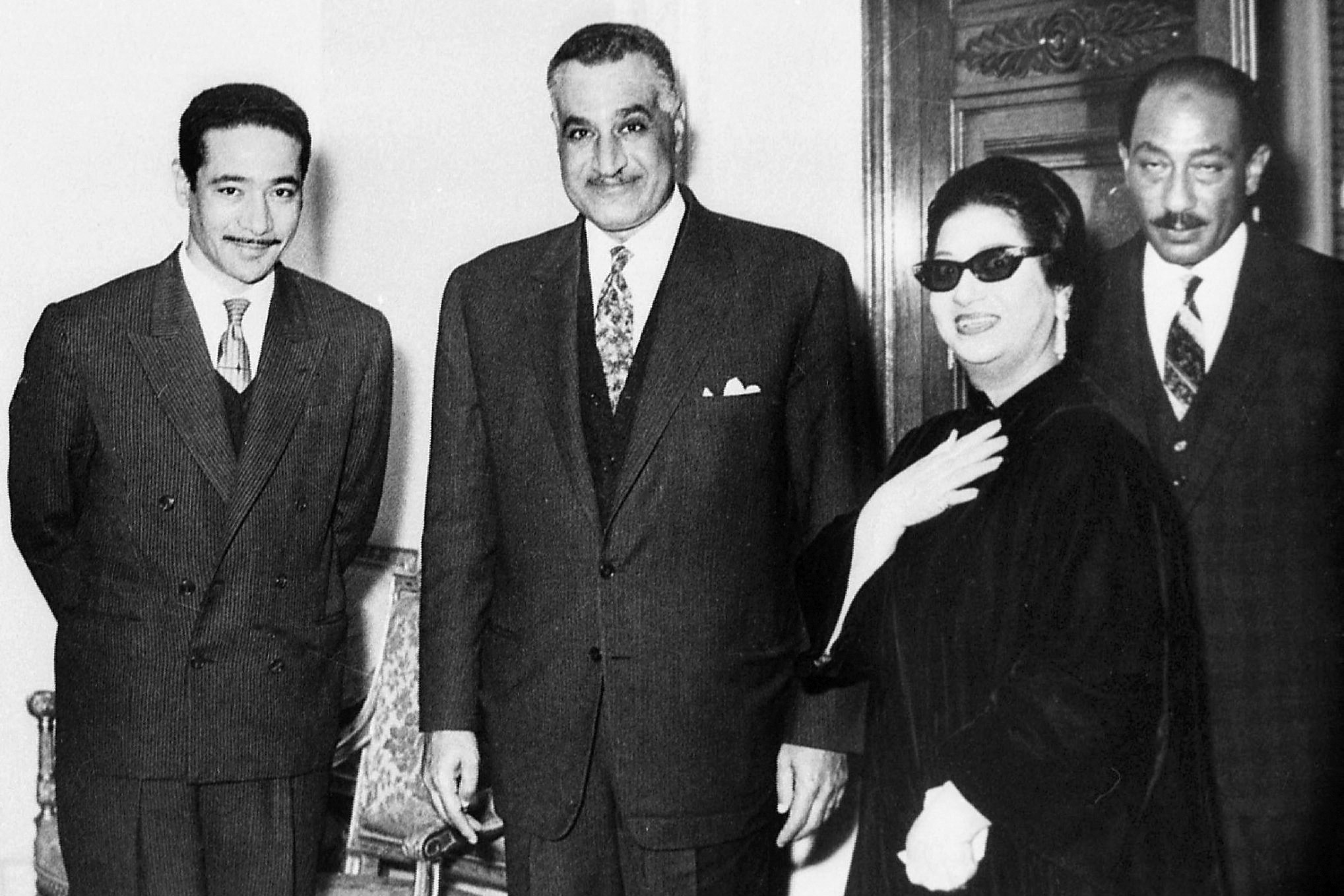

This evolution reflected the times, as popular sentiment had turned against British rule and the elites who collaborated with them. Umm Kulthum became a symbol of nationalism during a crucial time in the anti-colonial movement when she supported the Nasserist Revolution. Although, controversially, she had close ties with the monarch that had just been overthrown, she became an integral part of the postcolonial national identity in Egypt and in the promotion of Nasser’s Pan-Arabism.

Her legacy is deep and complex. People’s connection to her music is as emotional as the poetry she sang. She is entwined in the fabric of Arab society, and her music can be heard blaring out of the speakers of taxis, shops, restaurants and homes at all hours of the day. Her music makes a large part of the soundscape of Egyptian cities and the “noise” that defines them.

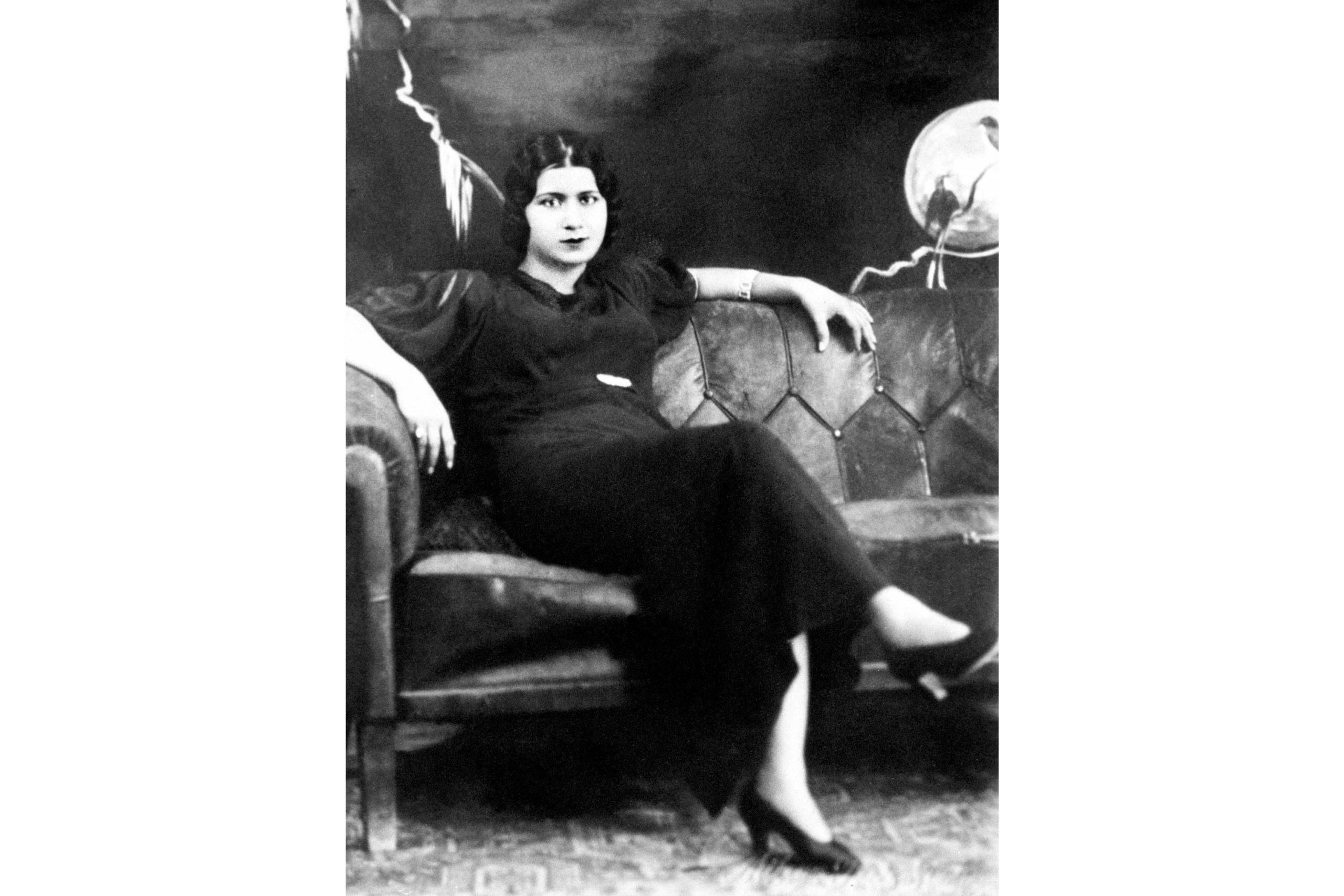

Born in a rural village in the Nile Delta around 1904, Umm Kulthum rejected gender norms throughout her life. As a child, she would memorise the religious songs her father and brother sang and performed to make extra income – songs not meant to be sung by girls. When her father heard her mesmerising voice, he dressed her as a boy to include her in their performances.

She later moved to Cairo to pursue a professional singing career after being encouraged by musicians who heard her sing. This was a time when women performing was still considered taboo – yet, her talent was impossible to ignore. She found success while making astute business negotiations on her own. Her strength, often spoken of, was in her character and the sheer power of her voice. She owned a stage full of men, often singing to audiences composed mainly of men, without getting intimidated or timid. She also became the president of the Musician’s Union, even though many opposed her because of her sex.

Poets and composers were drawn to her work and wanted to write for her, but she was very selective, dictating exactly what songs she would sing, while improvising and changing them as she saw fit. Her songs were often about longing, love, loss and romance. But they also encompassed many taboo topics and pushed gender boundaries by articulating womens’ desires, sexuality and political thought. Many are also open to interpretation and encompass dual meanings. For example, the love song al-Atlal includes this famous line: “Give me my freedom, release my hands.” It is a lyric that later became a slogan against colonial rule and Israeli occupation.

Postcolonial national identity

Although she had rural beginnings, her early career fame gained her status among the Cairo elite. At first, she was ridiculed for her “countryside” demeanour, but she quickly assimilated – she learned how to speak, dress and eat as a member of the elite class. She often performed for King Farouk I, the last monarch in Egypt during British colonial rule. He was ousted by the Egyptian revolution of 1952, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser.

The anti-colonial sentiments in Egypt at the time went together with a strong anti-monarchy stance (because of their collaboration) and led to Umm Kulthum’s music being banned from the radio by the new administration due to her performances for King Farouk. However, it is rumoured that Nasser immediately repealed this ban, apparently saying, “Do you want Egypt to turn against us?”

Nasser knew how beloved she was not only to Egyptians but to Arabs all over the Middle East, and also knew how powerful popular culture was in shaping a proud, national identity. It is said that she held ideologies similar to his and often spoke with the same nationalist rhetoric. Her endorsement of Nasser was a mutually beneficial relationship, as he had nationalised radio, music and all forms of public media. He knew she could also be a powerful unifier for his vision of Pan-Arabism. In fact, he devoted an entire radio station to her and would have her perform before and after his public speeches.

Related podcast:

Ethnomusicologist Carolyn Ramzy explains that Umm Kulthum, who could combine tradition, modernity and religiosity with an excellent command of the Arabic language, “also drew on a deeply rural and folked upbringing, an upbringing that was entrenched in the Egyptian countryside. And that gave her a real sense of authenticity. That’s why people saw her as bint el balad (daughter of the country)”. This tied in with the anti-colonial and anti-elite moment of the time as the country was pushing back the British colonial powers.

Nasser and Umm Kulthum found common ground. As Ramzy explains, “Nasser is also very much lined up with her background – not elite, not bourgeois, not part of the monarchy, but rather the counter narrative to the monarchy. One who celebrated the Arab Republic of Egypt, one who saw value in Egyptian folk and traditional ways of life, and who could speak to the experiences of the ‘common person in Egypt’.” So, they were able to work together seamlessly to entrench the nationalist project.

Using her power and relationship with her Arab audiences, she was able to participate in the shaping of a pan-Arab identity. Her voice was familiar and intimate, perforating both people’s homes and public life, legitimising Nasser’s in the eyes of many. On her trips to countries like Sudan and Morocco, she further promoted respect of each culture by wearing these regions’ respective traditional clothing, wanting to include herself as a part of it.

“These concerts in the Arab homeland have the power to display the shared feelings that tie together the Arab people everywhere and confirm that all of the Arabs are of one heart and one pulse,” she said.

Related article:

Becoming a powerful symbol of anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism, she also resolutely opposed the Israeli occupation of Palestine. She travelled across Arab countries, performing to raise funds for the military resistance against Israel. When Egypt and the Arab coalition of Jordan lost the six-day war of 1967 against Israel, grief overcame the nation, and Nasser resigned.

This is the period in which Umm Kulthum became directly involved in politics, releasing a song for Nasser to come back, fundraising for the military and mobilising women across Arab countries to participate in post-war efforts. Although it was a time of despair, her mobilisations sparked a sense of hope and strengthened pan-Arab solidarity.

Generational and diasporic journeys

Umm Kulthum’s music is difficult to understand for many who did not grow up listening to her or who are not accustomed to Arabic classical music. A general pattern among Arab youth is to have a disdain for the never-ending presence of her songs in their lives during childhood while finding love and understanding for it in later years. The lengthy notes, vibrations, and repetitions were tiresome to both me and my brother as children, and we hated it – complaining and pleading with our parents to choose something else or turn it off.

This was so for many young Arabs living both “at home” and abroad who were grappling with the confusion of Western supremacy and the legacy of colonialism in their lives. Umm Kulthum’s music was “too oriental”, reminding us a bit too much that we were outsiders and not Western enough.

As Leila Ahmed, feminist scholar, writes in her book, A Border Passage:

“She [Ahmed’s mother] and her sisters and other women relatives would gather together to make an evening of it, listening to one of Umm Kulthum’s concerts the first Thursday of every month. They would sit, consuming coffee and lemonade, smoking, relishing this singing as if it were some rich and subtle feast. To us children, it sounded like endless monotonous wailing. And we took care to make this plain to our schoolmates, sighing and rolling our eyes when we heard it. They did much the same, particularly children of Egyptians and other Arabs attending the English school. It was common, this looking down on Arabic music, among English schoolers. Arabic music was the music of the streets, the music one heard blaring from the radios in the baladi, the unsophisticated folk regions of town.”

Even the influential Edward Said – a scholar of postcolonialism and Orientalism – had a similar journey with Umm Kulthum. Despite growing up in Palestine and Egypt, he listened to mainly European classical music and American pop music. In his memoir, Out of Place, Said tells the story of attending an Umm Kulthum concert in Cairo in the mid-1940s. He found it to be a traumatising experience, describing it as “horrendously monotonous in its interminable unison melancholy and desperate mournfulness, like the unending moans and wailing of someone enduring an extremely long bout of colic”. In reference to the music, he “could not discern any shape or form in her outpourings, which with a large orchestra playing along with her in jangling monophony I thought was both painful and boring”.

Even as the thinker behind Orientalism, he himself projected certain orientalist tropes onto her music, describing European classical music as superior and a “universalist art form”. In later years, however, Said revisited his opinions in “Musical Elaborations” and came to the realisation that he had internalised the standards and values of Western classical music and could not appreciate the difference in approach to musical style.

Regardless of my feelings towards her at the time of my childhood, the music seeped into my being subconsciously because it was always there. I found myself feeling choked up with nostalgia at hearing Amal Hayati while walking into Andalousse restaurant in Cape Town. Even in this small North African restaurant in the middle of Woodstock, she was inescapable. But after having deep identity struggles growing up in the tiny Arab community in Southern Africa, this moment encompassed many feelings, emotions and realisations of the self-hate that we projected at the sound of Umm Kulthum. And, unsurprisingly, I could hum the complex orchestral melodies on autopilot while zoning out and allowing the flood of memories to consume me.

Today, like many other diaspora children who grew up with her music, I have grown to love the songs, the repetitions, the slight change in tone from one verse to another and the poetic words that move you beyond what any English song could.