The indefinable genius of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry

A personal reflection on the legacy of Jamaican producer and artist Lee “Scratch” Perry, known for his innovations in sound. Known for his eccentricity too.

Author:

10 September 2021

The stage is lit in luminescent blue and green. Smoke emerges from incense sticks inserted into apples and lemons that lie on a tray amid candles. The sign on the tray says “£$P” with a glowing stencil of a lion’s head attached to it. The DJ puts on a dub tune. Lee “Scratch” Perry emerges from the shadows slowly, toasting on the mic. He is wearing oversized biker boots with badges and broken mirrors attached to them, bright Superman pants, a wolverine T-shirt, a jacket made out of red glitter and a rainbow mohawk wig. His red beard emerges from underneath it. I am standing at the feet of one of my musical heroes.

The backstory to this surreal scene needs some context. It was September 2019. I had arrived two days earlier in Philadelphia for the first time – there to perform with Zimbabwean artist and choreographer Nora Chipaumire in her trilogy work #PUNK100%POP*N!GGA at the University of the Arts.

Scouting for gigs online, I was shocked to find a single Facebook post stating that Perry would be performing in a town called Ardmore, outside Philadelphia. It did not seem legitimate. I tried contacting the venue to find out if this was real, but received no response.

Being new to the city, I had no way of navigating my way around just yet. On that Sunday night, after much deliberation, I decided to venture out and find the train station. Eventually I hopped onto a train, still somewhat unsure, with the girl sitting next to me assuring me that we were headed the right way. An hour later, I arrived in the deserted, suburban town.

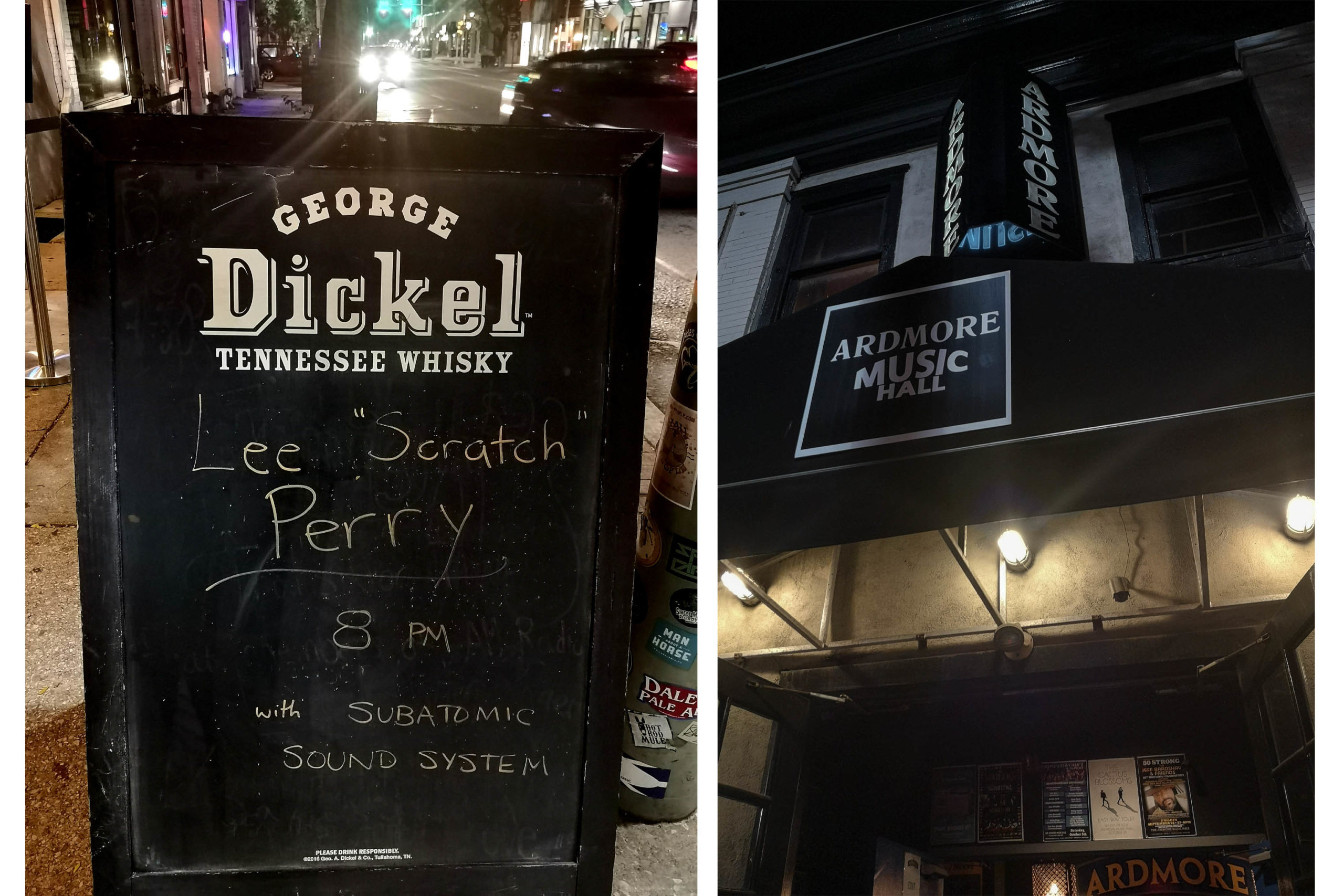

The venue, Ardmore Music Hall, was not far from the train tracks. A small pavement chalkboard outside it read: “Lee Scratch Perry, 8pm with Subatomic Sound System.” I was relieved. With no queue outside, getting a ticket was no issue. The venue was filled with a mostly white crowd, and felt completely out of place to have one of the biggest legends of music about to take the stage.

When Perry appeared, a few hours later, there was enough space in the crowd to move right to the front – which is where I watched him from for the next two hours. At 83 years old, he exuded incredible energy. He performed with his usual antics: changing hats during the performance and talking in rhymes and riddles throughout. Improvising over existing hits with some new material, Perry mostly had the crowd wondering what was going on.

Although it always felt like he was taking the crowd for a ride or sussing them out; while disguised as a madman, he was completely self-aware at all times. He laughed through some parts, and mumbled at others, drinking out of a chalice filled with luminescent green liquid. The crowd, which didn’t feel like Perry fans at all, given their responses, stared in amusement. But those familiar with Perry’s work understood completely.

Spectacle was central to Perry’s career. In an interview with Rolling Stone, he said, “Being a madman is a good thing!… It keeps people away. When they think you are crazy, they don’t come around and take your energy, making you weak. I am the Upsetter!” This alter ego of the Upsetter is one Perry embraced throughout his life – a disrupter, a punk and an outsider. “The ‘upset’ means to upset people – to bring them up – and another part of it means to destroy them…so the word is a two-edged sword,” he said about the title.

This September scene would not be the first time that I had ventured out alone to see him perform.

Soundclash systems

In 2010, while studying in Los Angeles, I saw him perform at a street festival on Sunset Boulevard. Again, he completely bewildered the crowd, not sure who the joke was on. The experience, like the one after it, was trippy.

It was uncanny, this coincidence, that in Chipaumire’s work my role was to layer records in a way that created a clash of sounds that would play out on a massive sound system – drawing from Grace Jones, Zimbabwe’s Chimurenga music, dub and noise. There were so many elements that linked our performance to Perry’s influence, especially the concept of soundclash.

In the incredible documentary The Upsetter: The Life and Music of Lee Scratch Perry, the artist talks about how the sound of dub emerged, and where he heard “the clash” come to him while doing construction work on the road. As someone who was self-taught and could not read or write music, his ear was behind his genius.

In the mid-50s in Jamaica, Perry got a job driving a tractor, helping to build the first road to Negril. “If I was not in Negril, I wouldn’t be a top producer,” he said. “Because it was when I was working with the rock, I pick up those sonic vibrations, and I hear the rock. When you throw the rock, it sounds just like when you hear the thunder roll, and I’m sure that’s where everything is coming from.

“So I hear, in those sounds, the clash and the drum… And in the wind I hear when the cymbal hit and I hear the rain, and I hear when the stone clash, and I hear the thunder roll and I hear the lightning flash….I learn everything from stone.”

A global influence

After Perry’s death on 29 August, tributes poured in from across the music world. While it would be impossible to capture the legacy of this artist in one piece, as his discography is so extensive, it is important at least to credit him as one of the pioneers of reggae and dub.

People Funny Boy, released in 1968, is known as one of the first songs to carry a chugging reggae beat. It was also one of the first songs to ever use a sample – that of a baby crying. Perry was also behind the production of Bob Marley and the Wailers’ finest recordings in the form of songs like Soul Rebel and Duppy Conqueror.

His music influences stretched beyond the music he created, from hip-hop to drum & bass. The tradition of toasting in Jamaica, which Perry would do regularly over beats, later influenced movements of freestyling and the birth of rap.

Related article:

Way ahead of his time, Perry used basic equipment to pioneer techniques that no producer had used before. These included recording microphones buried at the base of palm trees to get a different bass drum sound, running tapes backwards and using found sounds as samples. He would even blow ganja smoke over his master tapes to bless them.

Despite his achievements, Perry endured a lot of mistreatment and abuse from the music industry, and from musicians who used him for their own gain. He famously burnt down his Black Ark Studios – which he had built in his backyard – in 1983 for this very reason, saying that it was attracting bad energy. Perry also often confounded journalists in interviews, and has been labelled everything from a con man to a prophet. But he continued to make music and perform until his death. He even had gigs scheduled for later this year.

It was his fans who truly recognised the genius of Perry. He valued community and their love and respect helped revive his career. He would regularly send messages to fans on Instagram, once asking them to make magical hats to send to him to wear at performances. “I’m addicted to the people and the people are addicted to I,” he said in a recent interview with Sonos Radio.

An artist through and through

After living in Switzerland for 30 years, he finally returned to Jamaica this year. As depicted in many interviews, the walls of Perry’s home were painted with the words and poetry he wrote on them. His entire life was an artform – from the clothes and shoes that he personally made, the environment he created and lived in, to the music he made.

He was prolific not only in music, but in poetry and the visual arts as well. This commitment to artistry defined his entire universe. While some compared his eccentric nature to Sun Ra, or Salvador Dali, the truth is, there never was nor will there ever be a figure with quite the same genius as Lee “Scratch” Perry. His music exemplified his essence; the sonic sage lived his life to the tune of his own beat.