The human side of Joburg’s mosaic master

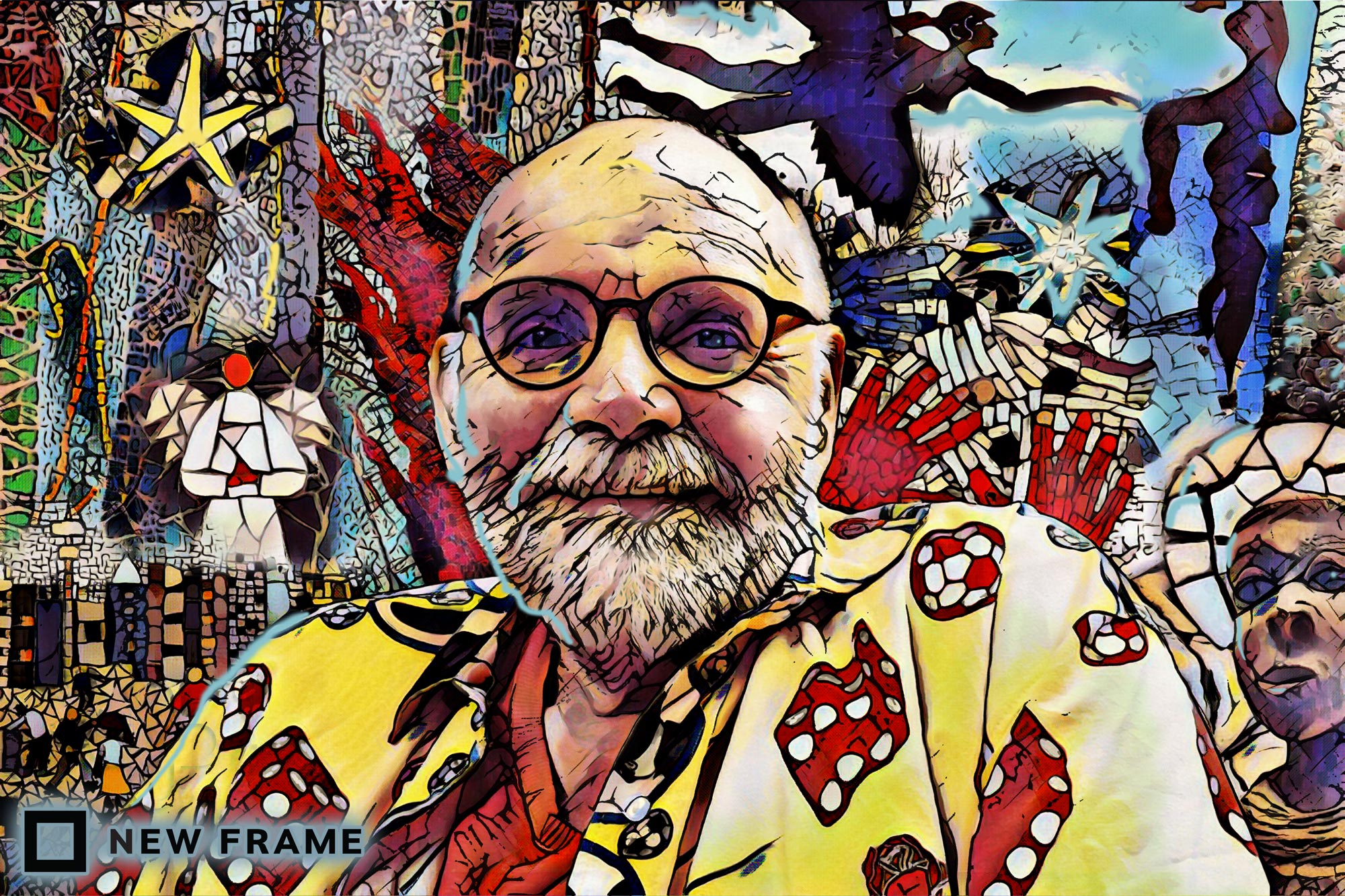

Andrew Lindsay was widely known for his mosaics and murals, but he’ll be best remembered for making art and heart matter in a city that can be as hard as stone.

Author:

25 October 2021

Sometimes it takes a thousand little pieces to make a big life, so big that you don’t notice the full picture until you zoom out – like a mosaic. It’s an apt metaphor for how Andrew Lindsay lived his 65 years as an artist, community activist, creative collaborator and exquisite connector of people.

Lindsay had a heart attack and collapsed in his garden late on the evening of 12 October. He died shortly thereafter. His untamed and fantastic garden – wild with carvings of angels, mosaics in the making, David Rossouw’s iconic giant metal art mobiles and the iThemba tower of light made of recycled plastic bottles that become a twinkling beacon at night – was, as his friend Dionne MacDonald says, not a bad place for “dearest Drew to die”.

The garden was a spillover from the Spaza Art Gallery that Lindsay founded in 2001, when he turned his Troyeville home into an anti-gallery, really. It didn’t conform to white-walled displays or the roundabout of the same heavyweight artists featured in solo exhibitions. Lindsay also ran the business as a not-for-profit. MacDonald says Lindsay was a creative entrepreneur, but his intention was for everybody to enjoy art, maybe start a collection too. It could not be the preserve of the wealthy.

Lindsay billed Spaza as “a showcase of all types of artists from all over South Africa”. He used the space not only for exhibitions, but also for poetry readings, pop-up long-table lunches, live music events and as a workshop and studio space he shared with other artists. Many of these artists came from the rural areas in which he had done art outreach and needed a place to start in the city. In recent years, he had turned parts of the property into Airbnb accommodation, quickly becoming a “superhost” and making new friends from around the globe.

Art for everyone

Spaza Art Gallery established itself as an art hub, an unpretentious gem and a Joburg must-visit. Once first-time visitors got over the visible neglect of the suburb that, in the past few decades, has slid from working-class tired to urban dilapidation and near worn-out, they saw something of how Lindsay saw the city: peopled, energetic, full of contradictions and collision points, but brimming with story and in no way ready to be written off.

Lindsay’s art commissions for the city placed him on the streets, among everyday people with everyday joys and everyday struggles. Somehow he took it all in, with no judgment.

His works have added to the public art heritage of the city in recent decades, marked with what City of Joburg head of heritage Eric Itzkin calls “his ability to speak to the environment and connect with people. His social awareness and connectedness set him apart. He worked without ego and pretension and developed people with a kind, democratic spirit.”

Lindsay’s work has included mosaicking under the Joe Slovo bridge; the Kliptown memorial to Petrus Molefe, the first Umkhonto weSizwe cadre to die in 1961; the mosaic of the Randjeslaagte Beacon marking the triangular site where Johannesburg was proclaimed in 1886; and numerous works that fill city park The Wilds. His works were prodigious and often had poignant back stories. The commemoration to the 1922 miners’ strike along Bezuidenhout Street in Bertrams saw him bring on board a group of 10 women from the neighbourhood who were victims of the xenophobic riots in 2008. Some of them became part of the women’s collective that made up his mosaic-making team over the years.

In one of his last major projects with the city he created The Ubuntu Memorial, a reimagining of the old Kensington World War I memorial site. He called it “a place of memory and loss” – not only an acknowledgement of the tolls of war, but also for those forgotten in a world easily pivoted to conflict.

Most recently he had been working with waste pickers and recyclers, helping them make mosaic house numbers to sell. He also mentored and managed many art projects over the years, including Andile Maswangelwa’s The Miner on Pixley Seme Street in the mining district. The sculpture recognises that the men who toil underground are the backbone of the economic wealth created in the country.

Lindsay’s friend Simon Mofutsana was one of the artists he mentored more than 20 years ago. “I met Drew when he came to Tembisa in about 1993 to work in the community. He shared with us his art skills and he was always kind and wanted us to learn all we could. He was a good person and it’s very sad that he is gone.”

They collaborated over the years and Mofutsana says he and Lindsay were about to start working on a new project when he died.

The ‘misery club’

For a man who came across as retiring and happy to be in the background, Lindsay was always looking forward to his next project and gently urging others to start, to push on or simply give something new a go. Inevitably, the “new” he pushed would be Biodanza, dancing that fuses music, movement and emotional expression. Lindsay danced with freedom and abandon, even in a body more ursine than gazelle. But understanding that the limits of the body are superficial made him a gifted Biodanza teacher who gave classes to those in wheelchairs and the elderly residents of an old age home.

Having had a heart attack and been diagnosed with congenital heart failure about seven years ago, he had taken his doctors’ advice to quit smoking. Along with dance, he adopted a daily routine of swimming laps in the Ellis Park pool. A lifelong friend who often joined him in the pool was Cati Weinek.

Weinek met Lindsay when he exhibited in the mid-1980s at the Market Theatre Gallery. Her father Wolf Weinek created the gallery as a middle finger to the “snobbish, elitist stuff going on in the north of Joburg”, she says.

“He became a family friend and also a dance partner for me. We would go clubbing together at places like Jameson’s, Kings of Clubs and also places where people of different race groups could gather under the radar.”

Lindsay, says Weinek, lived by principles of anti-racism and the spirit of community and humanity, and had a unique, infectious gentle positivity.

“We called our swims the ‘misery club’. We would say ‘life is shit and kak’ then we would swim and get out of the pool feeling like we left the heavy stuff behind,” she says of the humour and easy surrender that marked how Lindsay tackled life. Like the fact that he could totally pull off a pair of lime green trousers with a Clive Rundle creation. The fashion designer was a friend.

Talent and kindness

Lindsay grew up in the south of Joburg, the son of an art therapist father and a mother who encouraged her middle son of three to explore his creative and artistic talents. His brothers, Ian and Peter, were sportier and the ones who got away first when the three boys climbed neighbours’ walls to steal fruit, his sister-in-law Sharon Lindsay tells. Sharon, who is married to Ian, says, “He was eccentric, different, but it helped him learn early on how to see and solve the injustices in the world with warmth and kindness.”

She met the Lindsay boys when she was just 15. She tells that Andrew’s disinterest in sport as a boy would mean he’d kick a ball over a wall as far away as possible to end the game quickly, so he could go back to painting. Lindsay attended The Hill High School and here his talent for art made it clear that this was what would shape his career. And so it did.

Art, though, was simply the glue he used to hold his world together. A truer picture is that it was Lindsay’s compassion, depth of spirit and willingness to trust in the best in people that he used to shape bonds that mattered most.

His wish was for Spaza Art Gallery to be turned into a space to support artist residencies. His close friends are hoping to create a trust to ensure this dream becomes part of his legacy.

The #SaveSpazaArt initiative kicks off with a celebration of Lindsay’s life and a fundraising drive at the gallery at 19 Wilhelmina Street, Troyeville, on 30 and 31 October.