The horror, the horror of the corrupted heart

This Sharp Read examines two novels that demand reflection on the nature of oppression and imperialism in southern Africa and how – or whether – meaningful reconciliation can occur.

Author:

1 March 2022

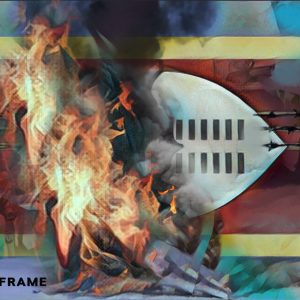

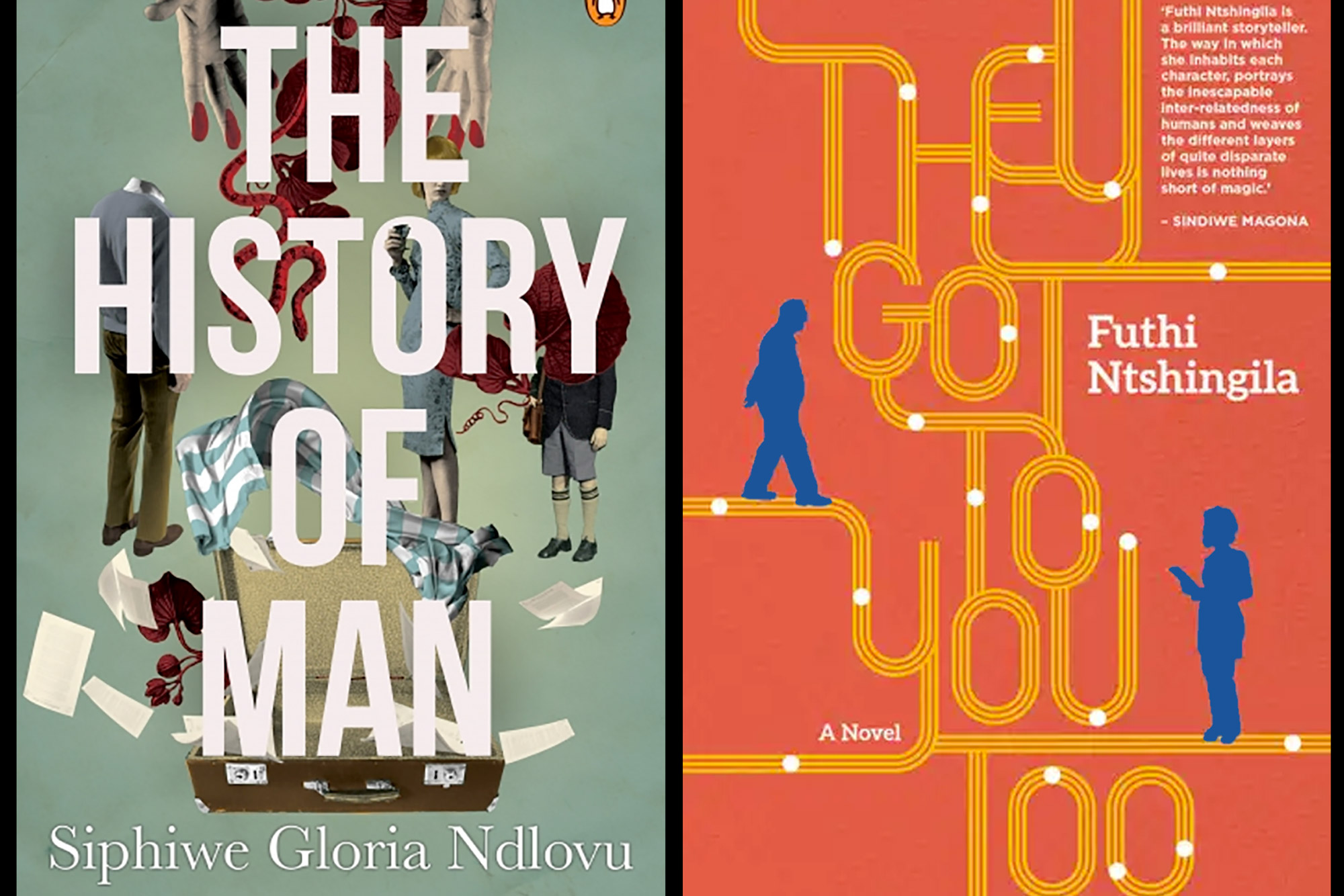

They Got to You Too by Futhi Ntshingila (Pan Macmillan, 2021) and The History of Man by Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu (Penguin, 2020) are timeous. Perpetrators – as members of South Africa’s apartheid security apparatus, or the Rhodesian army – are nearing the final chapters of their lives, and it’s just more than 25 years since South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established by Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu.

The History of Man by Zimbabwean author Ndlovu is an enthralling story of how one man’s heart is polluted by racism, and his life corrupted by colonialism. Set loosely in the 40 years leading up to Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, the primary location is then-Rhodesia, but the vagueness of place names and timelines harkens back to JM Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians in achieving a universality for its central message.

The novel’s opening line is both mundane and mortifying: “…Emil Coetzee was washing blood off his hands.” As the protagonist, Coetzee unfolds as an intricate, larger-than-life character, his drive forged in the tough outdoors and a semi-militaristic boarding school, the Selous School for Boys, with its motto, “Here boys become men of history”. The adult Emil wants to fulfil this ambition; he definitely wants love, but above all he must strive to create a legacy.

These goals are wrapped in his notions of identity. Coetzee’s lineage is hazy: “Your grandmother was a whore,” a family friend tells him, alcohol liberating truth. He loves the land – “He remembered his black shadow travelling the most beautiful land ever created as he explored the environs of the Matopos Hills” – but largely hates its people. He hits upon a mission: the formation of an independent Organisation for Domestic Affairs to document the “natives” so that they can have a history of their own.

Related article:

It’s a mindset in keeping with the attitudes of empire, but it has unintended consequences. When the civil war breaks out his bureaucracy has valuable information for the security forces. On the one hand he is vindicated. His archetypal racist friend Rutherford congratulates him as the “man of the hour”. “You stumbled on the very thing that the country needs to successfully fight the terrorists … You will become a man of history.”

But his organisation is quickly seconded into sinister activities, and once involved he is immersed in the regime’s ruthlessness.

And there is a faulty connection with the love of his life, the free-spirited Marion. She ends up marrying his erstwhile best friend, and he marries the daughter of a colonial capitalist. Happiness eludes them both except for brief, intermittent trysts – a state of affairs that mirrors his life, but for which he refuses to change.

The psychology of oppression

They Got to You Too by Pietermaritzburg-based Ntshingila opens shortly before Covid. In a Pretoria old-age home, 80-year-old Hans van Rooyen is reflecting on his life. The lucidity of his thoughts sharpens in direct proportion to the weakening of his body. He has much on his mind, a conscience that permits him no sleep, and – having spurned the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, without consequence – he now wants to talk.

Opportunity arrives in the form of a new caregiver. Zoe Zondi is his polar opposite. She grew up during the struggle period of the 1980s. Her family was torn apart by the violence, her boyfriend killed, friends left to join the armed struggle, and she emigrated to seek a better life. Her psyche is still scarred, but she exudes grace, and she senses talking may help her, too.

When the Covid lockdown is imposed, Zoe and Van Rooyen spend even more time together. Common ground is minimal, starting simply with mugs of hot chocolate. There’s an irony and an imbalance between the respect Zoe gives by calling him mkhulu (grandfather) whereas he refers to her as Girlie. Names are important, but it’s Zoe who understands that what’s more important is what’s in the heart. But, gradually, told in multiple first-person narratives switching between characters from their respective pasts, they both learn more of each other’s lives.

Both novels explore the psychology of oppression. The History of Man assesses the corrosive impact upon the oppressor himself or herself, while They Got to You Too also offers a victim’s vantage, albeit a secondary one.

Related article:

How minds become warped is complex, so Ntshingila and Ndlovu dig into the ancestry of their protagonists. Van Rooyen’s reliance on Black caregivers reawakens his childhood feelings of love and trust for his Black nanny, Kristina – effectively his only source of parental affection and nurture, because his mother died giving birth to him, and his father returned from World War II damaged, embittered and irredeemably racist. We learn of his forebears, stretching back to the South African War, when Van Rooyen’s grandmother, Omagrootjie, corralled resources to keep her family and an extended community of local women alive – including Kristina and the other Black servants, to the initial disgust of the other women of the volk.

Ntshingila expertly weaves in the ancient parable of Truth and Lie: Kristina tells a young Hans how Truth gets tricked by Lie into swimming naked, and when Lie steals her clothes she is left in a quandary. In her nakedness no one wants to address her; everyone prefers the dressed-up Lie, so she sinks back and hides under the water.

At the age of 10 his father shunts him off to boarding school. The goodbye is achingly simple: “You are a good boy,” Omagrootjie tells him. “Go well my child and always remember the story of the naked Truth. She is right here,” Kristina says, touching his heart.

How he mutated from a sensitive and caring boy into an agent of state-directed violence is the core of the book’s discovery, but part of its complexity is that we never find out precisely what he did – and although he is only partially remorseful, we empathise with Hans the man even as we despise Van Rooyen the Border War leader and South African Police general.

Intergenerational poison

In The History of Man, Emil, too, had been a loving child, and befriended the other acutely shy and sensitive boy at the bullying boarding school. Why did Emil’s and Hans’s hearts not prevail? Van Rooyen and Coetzee are capable of deep reflection; they see now that they committed dastardly deeds in service of a tainted ideal – a falsehood that was brainwashed into them.

This intergenerational transfer of attitudes is extraordinarily difficult to break. “Ah, they got to you too,” says Kristina when 14-year-old Hans returns to the family farm on holiday from boarding school and, utterly changed, ignores her. It’s a repeat of what she had said to Van Rooyen’s father when he returned from the war and uprooted her from the family home to the servants’ quarters. This time, her ironic, piercing laugh comes with a sad rejoinder to young Hans: “Always remember the naked Truth. She’s going to climb out of the water any time now.”

Guilt, too, accumulates as a slow but sure intergenerational poison. Familial bonds become fragile when gnawed by fathers seeing themselves in their sons, the guilt amplified by its regeneration. Or, when secrets have to be kept in the hope of preventing outright schism.

Both protagonists become estranged from their sons, who are shocked by the attitudes and actions of their respective fathers. Coetzee’s and Van Rooyen’s sons courageously break the cycle of toxic masculinity, but for both this creates different forms of heartbreak.

Related podcast:

The scars of trauma also blight future generations, especially when not acknowledged. “By not dealing with past human rights violations, we are not simply protecting the perpetrators’ trivial old age; we are thereby ripping the foundations of justice from beneath new generations,” wrote Antjie Krog in Country of My Skull, the seminal 1998 reflection on and compendium to the TRC. As an operative, not just a witness, and now in his “trivial old age”, Van Rooyen understands how wrong this would be. In a sense, he is lucky, on many counts: righteous women of different races were involved in his upbringing and imprinted a moral residue, and his current caregiver, Zoe, is non-judgemental and compassionate.

But does he grasp how wrong it is that he has never had to face justice? Is it fair that Zoe is his confessional, that she has to bear what he chooses to convey of his load? His tales are shaded by a residual unwillingness to wholly account or to apologise unconditionally. “I used to do those things to women and I particularly hated women who put up a fight. A part of me prays that I die before I have to tell my Girlie that part of my story.”

Ntshingila writes with this kind of plain, colloquial language, adding credibility to how a conversation, no matter how grave its topic, might flow between different generations and races in South Africa. By comparison, Ndlovu’s text benefits from concentration so as to grasp the literary references, metaphors, and allusions to liberation heroes.

Dystopia – or an alternative

Besides some similarity to Waiting for the Barbarians, Ndlovu’s portrayal of Coetzee also references Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Something triggers episodes of derangement; it may be an overbearing cognitive dissonance, Coetzee’s subconscious revulsion at what his job entails. Coetzee’s tragedy is his realisation of how little he achieved despite grand plans, a firm belief and committed actions. But that’s his tragedy; for the country, for humanity, it is that he succumbed to brutal impulses within his make-up, and that his organisation contributed to the subjugation of others.

Ultimately, even in love he is shown to be obtuse. Marion sends him letters with extracts from Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston, as clues to her feelings, her very being. He can’t be bothered to try to understand her message: “He chuckled to himself as he briefly wondered if Zora Neale Hurston was yet another Black writer.” He admires, lovingly, only Marion’s handwriting. Finally, revealing all at great personal sacrifice, she invites him to reconcile, but he rejects her, his heart hardening again in its insistence at distance from even a drop of Matabele blood.

An identity-driven purpose, then, has been futile for the main characters in both novels. Their legacies are in tatters; that is, they were built on falsehoods. With her minimal use of time and place specificity, Ndlovu reminds us that this is still happening today: news cycles replay rising authoritarianism, the suppression of minorities, police brutality even in apparently leading-light democracies. If we continue to choose to live in bubbles like Coetzee’s, Ndlovu says, The History of Man will be our dystopian future.

But there are alternative avenues, leading to redemption and healing. They Got to You Too hints at the multiplicative power of mercy and forgiveness. Under the right circumstances, shared humanity can be rediscovered – a point made by Cynthia Ngewu, among others documented in Country of My Skull. The mother of Christopher Piet, slain in 1986 in the infamous Gugulethu Seven incident, Ngewu testified at the TRC that “this thing called reconciliation, if I am understanding it correctly … if it means this perpetrator, this man who has killed Christopher Piet, if it means he becomes human again … so that I, so that all of us, get our humanity back, then I agree, then I support it all”.

Related article:

Even when forgiveness is withheld, there’s healing in the telling. Confession, in stripping away the lie and at least some hubris, can transform. Van Rooyen has chosen, belatedly, to start down this path. But in The History of Man, Coetzee remains defiant to the end, and Ndlovu is more cryptic on what comes next, partly because her book correlates with the cusp of colonialism’s concluding chapter. What’s missing in the story might literally be a sequel, progressing, so to speak, in time.

Progress and time: the writer and activist James Baldwin fumed about these words in the documentary The Price of a Ticket, expressing outrage at the notion that more time is needed to build bridges: “What is it you want me to reconcile myself to? You always told me it takes time. It has taken my father’s time, my mother’s time, my uncle’s time, my brothers’ and my sisters’ time, my nieces’ and my nephews’ time. How much time do you want for your ‘progress’?”

Where The History of Man is mesmerising, They Got to You Too is subtle. Both prompt feelings of disgust at the root causes of our histories, dismay that within them there is still so much with which to get to grips, and hope that younger generations, in their judgement, will be wise.

Both books are moving reminders that the corrosive stains of colonialism, apartheid and racism have made too many southern African generations hostages to history. If we are all to get our common humanity back, soon, we need to find the point of intersection between accountability, remorse and forgiveness.