The good works of the Sir Alba Arts Academy

Dancers from the small academy in Etwatwa are winning locally and qualifying internationally, but will never compete overseas unless the institutions meant to support such initiatives actually do s…

Author:

29 June 2022

The township of Etwatwa on Johannesburg’s East Rand is one of the oldest in South Africa, having been established in 1985. In recent times it has become known for gangsterism and retaliatory vigilante violence in the form of “necklacing”, a testament to the endemic structural challenges communities such as this endure when authorities do not do their work or simply do not care. And young people are often the ones who pay the price, both as perpetrators and victims of violence.

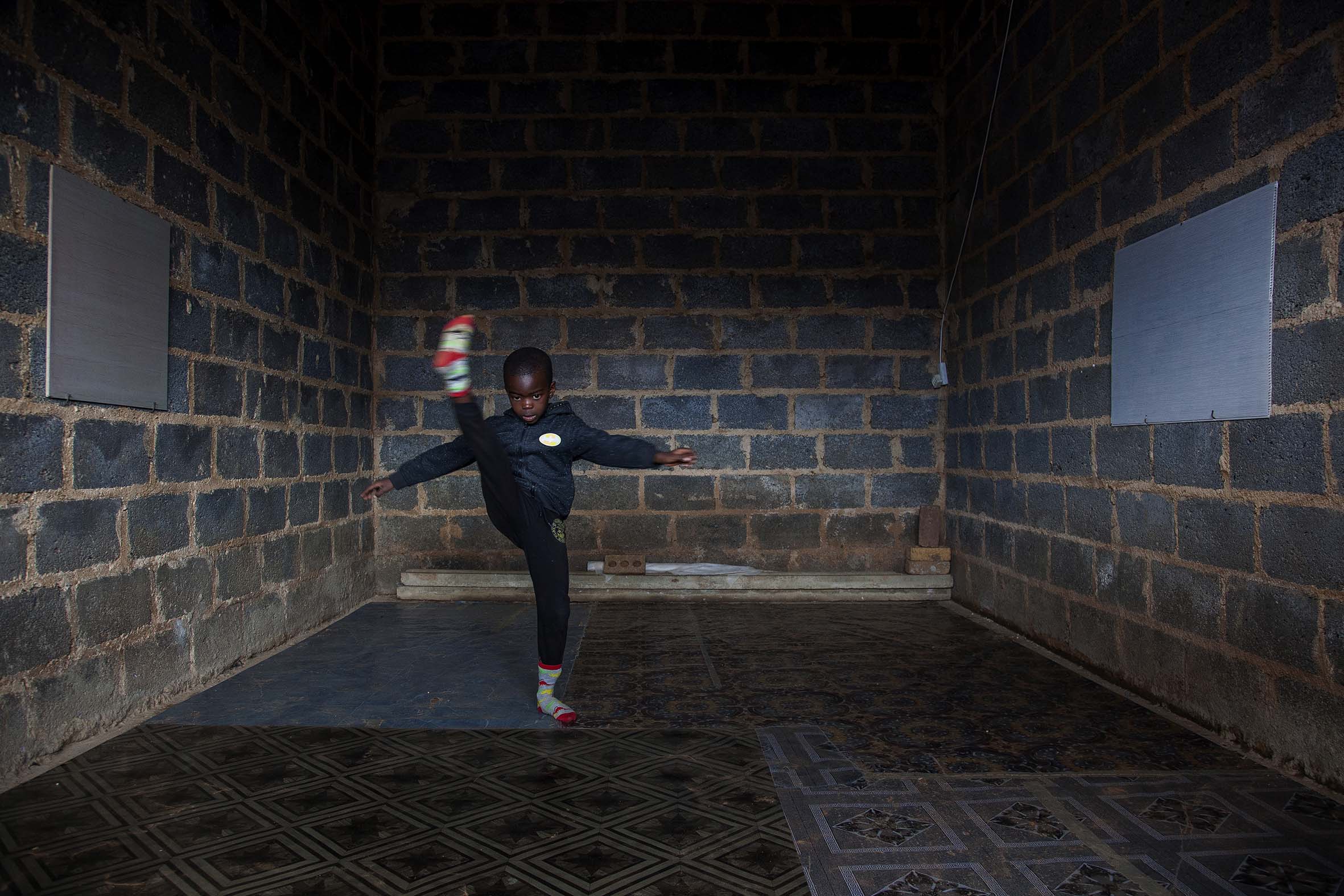

The Sir Alba Arts Academy was started by Albert “Sir Alba” Mabunda with friends who shared a passion for the arts. The academy offers hope for an alternative reality for the children and young people it serves, giving them arts training, an after-school programme and other forms of support. Around 40 children and young people are enrolled, with more wanting to attend but unable to because the space available is limited.

“In 2008, when I started this organisation, there was a lot of gangsterism in Etwatwa … and a lot of teenage pregnancy, school dropouts and the youth had nothing to do. So I was this person who had a bit of training in terms of performing arts. I saw the influence I had in the community, people could listen to me because they know my work, so I thought why don’t I bring it back home and establish this as an organisation,” says 36-year-old Mabunda.

His love for the arts and performing started at Dr Harry Gwala Secondary School near his Etwatwa home. At the urging of his teachers, he dabbled in debate before joining the drama class, where he excelled at writing. After his father died, he joined the Healing Centre Family Church, which staged many productions every year. “From there, we established an arts ministry where church youth would come for rehearsals and do productions,” he says.

Over the years, Mabunda has trained and taken children from the crèche where he was working to the SA’s Got Talent finals. He’s also taken hip-hop and contemporary dance groups from his academy to competitions such DanceStar South Africa, Dance World Cup South Africa and the South African Dance School Championships to expose them to different platforms. In 2018, against all odds and on the first attempt, they won gold and a chance to represent South Africa at the world championships. Unfortunately, they could not attend because of a lack of funds. Many of the children do not have passports either and parents were reluctant to sign the required paperwork.

The struggle for a home

Helped by a local councillor, Mabunda put up a temporary structure next door to the Stompie Skosana Hall in 2018 to house the academy.

But in October 2021, the Ekurhuleni Metro Police Department issued him with a 14-day eviction notice, the “reason” being that his academy lured “nyaope boys” to the area. After ignoring the order, he woke up one morning in December 2021 to find the structure destroyed.

The academy was then housed temporarily at the Chris Hani Sport Complex, which has good facilities, but Mabunda was evicted again because of the Covid-19 pandemic. He now operates the academy from the garage of his parent’s house in Etwatwa.

John Morajane, 47, is a community leader who has supported the academy over the years because it provides a “safe space” for children and young people in the Etwatwa community.

“It’s easy for perpetrators to get to these children when they are vulnerable on the streets, so this project is a good thing for the community. It teaches a lot to the children and we need to groom these children, which is what the academy is doing,” says Morajane.

Ayanda Tshabalala, 22, is a student doing drama and dance at the academy, having completed a six-month training programme at the Sibikwa Arts Centre in Benoni. The academy has given her an opportunity to refine her performance skills.

“A place like this saves a lot of kids from doing wrong things. And when you do these kinds of activities your mind gets active, you get to think properly because you are always performing, meaning your body is active,” says Tshabalala. She adds that the government should provide an adequate venue for the academy as the challenge of space is immense, especially when it comes to dance classes.

Township talent

Bongane Nkosi, 19, is a self-trained contemporary dance instructor who has just engineered Sir Alba Arts Academy’s latest success. A group from the academy won a dance tournament and have the chance to represent South Africa at the world championships in Spain.

He believes in the academy’s vision and how it positively affects the community. “I want to see each and every artist being independent, because we need people who can give us opportunities. Unfortunately we can’t find them, so we need to be there for ourselves,” says Nkosi.

For him, the government assisting with a permanent space is vital to the success of the academy. “We have been through many spaces, some which have been demolished, some of them are dilapidated. So a permanent space for us is what we need help with.”

For Mabunda, these interventions are important to ensure that this talent is not lost because there is no support. His mission to raise funding for the trip to Spain continues, even as he shares the latest rejection emails from the National Arts Council and the Department of Sport, Arts and Culture – whose role is and should be to support such initiatives. They are found woefully wanting though, as evidenced by the recently proposed R22 million, 100m flagpole that caused a public outcry until it was suspended indefinitely.

“Townships are filled with talent. You see it through the graffiti you see on the streets, boys dancing at the robots, through heritage days at schools, a book of a learner not coping in academics but who has lots of cartoons drawn in his book, boys and girls who want to be deejays… But unfortunately the government is mining in the wrong places and using documents to stop artists from accessing funding. The gatekeepers are killing the arts,” says Mabunda.