The gift and curse of Musa Juwara’s success

The rise in the number of Gambian footballers making a name for themselves in Italy’s Serie A is something for the African nation to celebrate. It’s also a cause for concern.

Author:

21 October 2020

The success of Musa Juwara is a source of pride and a cause for concern for The Gambia. The teenage sensation who is on the books of Italian club Bologna and currently on loan to Boavista FC in Portugal has won many hearts with his performances, more so because of the road he has travelled to stardom.

But first, the cause for concern. In April 2019, the European Union (EU) launched a youth empowerment programme in The Gambia to tackle the root causes of the country’s migration. It was called Tekki Fii, a Wolof term that means “make it here”, a goal many Gambians struggle to achieve.

“Many of the Gambians who decide to migrate do so in order to advance their economic opportunities,” Germany’s Arnold-Bergstraesser Institut (ABI) for cultural studies said in a report titled The Political Economy of Migration Governance in the Gambia. The country has been heavily affected by dictator Yahya Jammeh, who was voted out in December 2016 after 22 years as president and forced into exile in early 2017.

“In 2020, the situation has gotten even worse due to the pandemic. Things haven’t really changed that much, despite the election of Adama Barrow and the transition to democracy. Discontentment about the government is growing, because Gambians are not happy with their decision-making,” says political scientist Franzisca Zanker, the co-author of the ABI report alongside Judith Altrogge.

Related article:

The difficulty of setting up a decent life in The Gambia was particularly evident between 2013 and 2017. In that period, around 38 500 people left the country of just over two million in search of a better life. Many of those who emigrated were minors. Italy, one of the first European landing countries on the central Mediterranean route, registered about 25 000 unaccompanied minors in 2016, 13% of whom were Gambian.

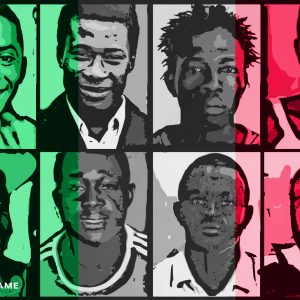

From the aforementioned percentage of minors, a few have surfaced and made headlines in Italy as a result of the most popular sport in The Gambia: football. This is what elicits pride, like the success of 22-year-old Catania midfielder Kalifa Manneh and 19-year old Ebrima Darboe, a midfielder at AS Roma.

And then there is Juwara, who arrived in Messina, Sicily, on 10 June 2016 when he was 14. Germany’s FGS Frankfurt rescued Juwara and 535 other people from a rubber dinghy as they crossed the Mediterranean Sea. Following some impressive seasons in the youth divisions with Virtus Avigliano – a team based in the province of Potenza, where Juwara was resettled after his arrival – and Chievo Verona, the 19-year old moved to Bologna last year, joining countryman Musa Barrow.

Both Bologna FC’s players and The Gambia have been in the spotlight after Juwara and Barrow scored against Inter Milan, giving their team a late comeback win at San Siro in July. Juwara’s success has highlighted the plight many of his compatriots endure in their migration to Europe. While his story ended well, others end in death or life in the lower ranks of Italian football.

A bright future for The Gambia

Juwara and other minors’ experiences run counter to the smooth journey of players like Barrow, 20-year-old Atalanta midfielder Ebrima Colley and Vicenza forward Lamin Jallow. They were scouted by Luigi Sorrentino, an Italian football agent who has travelled regularly to The Gambia since 2012 to look for new talent. Over the years, Sorrentino was able to forge relationships with the best Gambian clubs, in particular Hawks FC, from which Barrow and Colley come. Despite a clear lack of professional organisation, he is convinced that Gambian football “is gradually booming”.

“If only the government could invest in facilities and efficient academies, young people would probably remain and we could see more Biri Biris,” said Mustapha Sallah, referring to the late Gambian footballer who is regarded as one of the country’s best talents. Sallah is a Gambian returnee who interrupted his journey to Europe, using the EU’s International Organization for Migration joint initiative to return home from Libya.

“We don’t have a professional league, so as long as they don’t take care of football, the dream [of leaving] will always be there … It’s needless to say that we would like to see more examples like Musa Barrow and Omar Colley [a defender at Sampdoria in Italy] who haven’t had to undertake the hardest of ways.”

On returning to The Gambia, Sallah founded Youth Against Irregular Migration, an organisation that campaigns against the dangerous migration trip to Europe.

Related article:

“Many Gambians are not well educated [the overall literacy rate is 55%, according to the 2020 CIA World Factbook] or don’t master a specific job. We play football every day, so it [turning professional] is something we normally talk about in The Gambia. It is always part of the dream. When I left, I did it for an educational purpose, but I also aspired to become a professional sportsman for a while. I wanted to become a basketball player … but courts weren’t there. We didn’t have a place where we could train properly, that’s why it is only natural to leave to pursue our dreams,” says Sallah.

Five of the nine professional or semi-professional Gambian footballers who are currently in the books of Italian clubs have followed the dream Sallah talks about. Virtus Verona goalkeeper Sheikh Sibi, who plays in the third tier of Italian football, left when he was 16 years old. “I wanted to explore the world, chase my dreams… and football was the main part of them. Both the desire of improving my life and becoming a footballer were intertwined,” says Sibi.

“The foundation of our football is not suitable. I used to play in an informal academy based in Talindi. It was called Football Heroes … and I’m guessing it wasn’t even registered.”

Behind the rise of Gambians in Italy

Considering the talent among Gambian footballers, why are so many only showing up recently, especially in Italy?

“Gambian talents weren’t hiding, it’s just that the way Italian football is set up and the laws for migrants aren’t favourable at all,” says Buba Jallow, a Gambian freelance journalist based in Sweden.

Darboe and Juwara had a complicated battle with Italian and international sports regulations that limit the entry and registration of players before joining ASD Young Rieti and Chievo Verona, respectively. A few years ago, Bakary Jaiteh missed the opportunity to join AS Roma as he couldn’t obtain the necessary paperwork.

Article 19 of the Fifa regulations on the status and transfer of players forbids the transfer of underage players outside their country. Consequently, the cases of Juwara, Darboe and other Gambian minors represent real exceptions. This is despite the Italian Constitution and its immigration law expressly protecting the right of all individuals who regularly stay on the territory of the state to exercise the right to associate and, in particular, not to be the subject of discriminatory treatment.

On 4 August, the Italian football federation’s federal council upheld the rules governing the registration of non-EU footballers, once again confirming the same restrictions that have been in force for 10 years. Points C and E of the official statement say that second- and third-division clubs can’t register non-EU footballers coming from abroad or non-EU footballers who already play in the Italian amateur leagues.

This regulation prevents many African footballers and those outside of the EU from climbing the Italian football pyramid. The Gambian player who plays in an amateur league will be forced to remain there, not being able to aspire to reach professionalism, unless they are so talented that they attract interest from first-division clubs. And the chance of the latter happening for players in The Gambia is remote, as Serie A teams can only register two non-EU players and would hardly use those two slots for players who have no experience in professional football.

Related article:

“It is time to reset the system [of the transfer and registration of foreign players] and identify the key principles around which we should rethink and rewrite the rules on the enrolment of non-EU players,” says Vittorio Rigo, a sports lawyer with much experience in the field of registration of non-EU players and unaccompanied minors. In 2017, he successfully fought Juwara’s case.

“In the last 20 years the world has changed, and the current rules are designed for a reality that no longer exists. Since the Italian National Olympic Committee and its Football Association introduced the first restrictions in 2002, they have undertaken a series of regulatory measures that they have stratified in a fragmentary way.

“Today there is a system that lacks reasonableness, because similar situations sometimes lead to opposite results. The mechanisms are so complex that it would not be easy to explain to a young Gambian player all the possible variations and exceptions. It is necessary to create a movement of opinion that pushes towards a radical change of perspective, because unclear rules could favour illegality.”

The double-edged sword of minors

“At some level it is all about reaching Europe. Families are waiting for money. They don’t care about your job. So you can’t sit down and wait for the documents in order to play football, you would rather look for any job to sustain your family,” says Sallah.

“When it comes to migration, we have to take into account that everyone who decides to leave has a big responsibility,” adds Jallow.

“Yes,” agrees Sallah, concluding that “in this context, minors are luckier because they don’t feel the high pressure the families usually put on those who leave, at least initially. So they have more opportunities to become professional footballers and, as the years go by, those who left when they were minors are emerging and are actually the ones who are making us proud.”

Juwara’s success is a story of hope and resilience. But it’s also a story of caution and a cause for concern, as the trek to Europe kills many Africans in the Mediterranean who dream of a life like Juwara’s.