The gendered violence of everyday life

Addressing violence against women means expanding our definition of violence to encompass all of the sources of harm, from the global economy to climate change.

Author:

4 February 2020

Less than a month after Canadians marked the 30th anniversary of the 1989 École Polytechnique Massacre – during which Marc Lepine murdered 14 women and injured 10 others on a college campus in the name of “fighting feminism” – trans activist Julie Berman was murdered in Toronto. A woman/feminised person is killed in Canada every 2.5 days by their intimate partner, and one third of women/femmes will experience at least one incident of sexual assault in their lifetime.

Berman’s murder also reminds us that the category of “woman” does an injustice to the diverse realities of living in a femininised body. While women/femmes who are marginalised by gender identity, sexual orientation, ability, age and race are more likely to experience physical and/or sexual violence, they are additionally marginalised by their exclusion from consideration and conversation on gendered violence.

Related article:

In Canada, the subject of gendered violence is revisited yearly on 6 December. But we acknowledge that gendered violence will be a part of our societies every day until this date next rolls around. We acknowledge that the “woman” to which we devote our energy and attention on this day is, too often, defined according to the needs and experiences of the most privileged. And, we acknowledge that while we find most comfort in the passive pursuit of remembering, the issue of gendered violence is a current issue that calls us towards action.

Of course, this “action” must include addressing the violently misogynistic ideologies responsible for the massacre at École Polytechnique, and so many incidents since then. But we cannot miss a critical piece of the puzzle: our own participation and investment in patriarchy.

Patriarchy is a structuring force of our societies, one that organises, directs and coordinates the lives of all us who live on this planet. It is easy enough to condemn those driven by a seemingly irrational hate of feminised people. It is less easy to consider the ways that we ourselves benefit from this system – including many of us who identify as women.

Patriarchy and the global economy

Patriarchy is a feature of our global capitalist economy, making possible our material abundance.

Consider fast fashion – sustained by sweatshop labour, up to 90% of which is supplied by women. Those working in sweatshops are paid as little as 6 cents per hour, work 10 to 12-hour shifts – with frequent mandatory overtime – and have restricted bathroom and water breaks. Sexual harassment, corporal punishment and verbal abuse are regular disciplinary tactics. And the work is often lethal, exemplified by the 2013 Rana Plaza Collapse in Bangladesh, the deadliest structural failure incident in modern human history. The majority of the 1 100 people killed and 2 500 injured were young women employed as garment workers in the building – forced back to work despite knowledge that the building was unsafe. The disaster is a shocking reflection of the dehumanisation of women in the Global South – one that both enabled the disaster to occur, and that has determined the responses to it.

Related article:

The Supreme Court of Canada dismissed a lawsuit against the Canadian supermarket chain Loblaws by the family members of victims, who were producing clothes for the company’s “Joe Fresh” label. The court held that Loblaws had no duty of care to those workers and ordered victims to pay back almost $1 million in legal costs.

The gendered aspect of sweatshop work is not incidental but intentional, critical to the functioning of a fast fashion industry dependent upon cheap labour. As one female Bangladeshi factory worker said via the Clean Clothes Campaign, “Women can be made to dance like puppets, but men cannot be abused in the same way. The owners do not care if we ask for something, but demands raised by the men must be given some consideration. So they do not employ male workers.” As Jennifer Rosenbaum, US director of Global Labour Justice, said about the retail industry, “We must understand gender-based violence as an outcome of the global supply chain structure.”

Agriculture and mining – two other massive global industries responsible for our lifestyles of thoughtless plenty – are similarly financed through the exploitation of Global South/racialised labour, with women in these lines of work particularly vulnerable to underpayment as well as sexual violence and physical harm.

Patriarchy and climate change

Patriarchy distributes the harms of capitalist wreckage of the environment, ensuring that those who have contributed the least will experience its impacts the most.

In a report released this summer, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights Philip Alston describes how, “even under the best-case scenario, [climate change ensures that] hundreds of millions will face food insecurity, forced migration, disease and death.” The richest 10% in the world are responsible for 50% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and in Canada we are particularly guilty. Per person, we produce more emissions than any other G20 economy. Perversely, while the poorest half of the world’s population is responsible for just 10% of worldwide carbon emissions, developing countries will bear an estimated 75% of the costs of the climate crisis. And within this west versus east, rich versus poor, Global North versus Global South divide, gender inequalities exacerbate the injustice of climate change.

As the International Union for the Conservation of Nature explains, “Women are often responsible for gathering and producing food, collecting water and sourcing fuel for heating and cooking. With climate change, these tasks are becoming more difficult. Extreme weather events such as droughts and floods have a greater impact on the poor and most vulnerable – 70% of the world’s poor are women.”

Patriarchy and economies of war

Patriarchy allocates the “benefits” and “costs” of war, allowing those who reap its material/financial reward to remain sheltered from its devastation.

Despite evidence that Canadian arms are being used in the war in Yemen, our government has failed to cancel its lucrative weapons contract with Saudi Arabia. In a briefing last July, the Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock, indicated that the conditions “for most people in Yemen are getting worse”. Around 100 000 people have been killed; over 85 000 children are dead from famine; and 13 million are at risk of starvation. According to the United Nations Development Programme, a continuation of war ensures that Yemen will become the poorest country in the world, where 79% of the population will live below the poverty line, and 65% will be in extreme poverty by 2022. Women always disproportionately suffer the effects of war, and this is true in Yemen.

According to the UN, more than 3 million Yemeni women and girls are at risk of domestic violence, while 60 000 are at risk of sexual violence. Women are also the most vulnerable among the 10 million who rely on food aid because they are expected to eat only after the men and boys have eaten. Over a million breastfeeding or pregnant Yemeni women are malnourished, many of whom already face life-threatening challenges because of a lack of reproductive services.

Yemen has, for years, been ranked at the bottom of the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report, and any gender progress over the years has come to a halt, since, in the words of CARE gender activist Suha Basharan, “with the war, finding food became the priority, not talk about rights”.

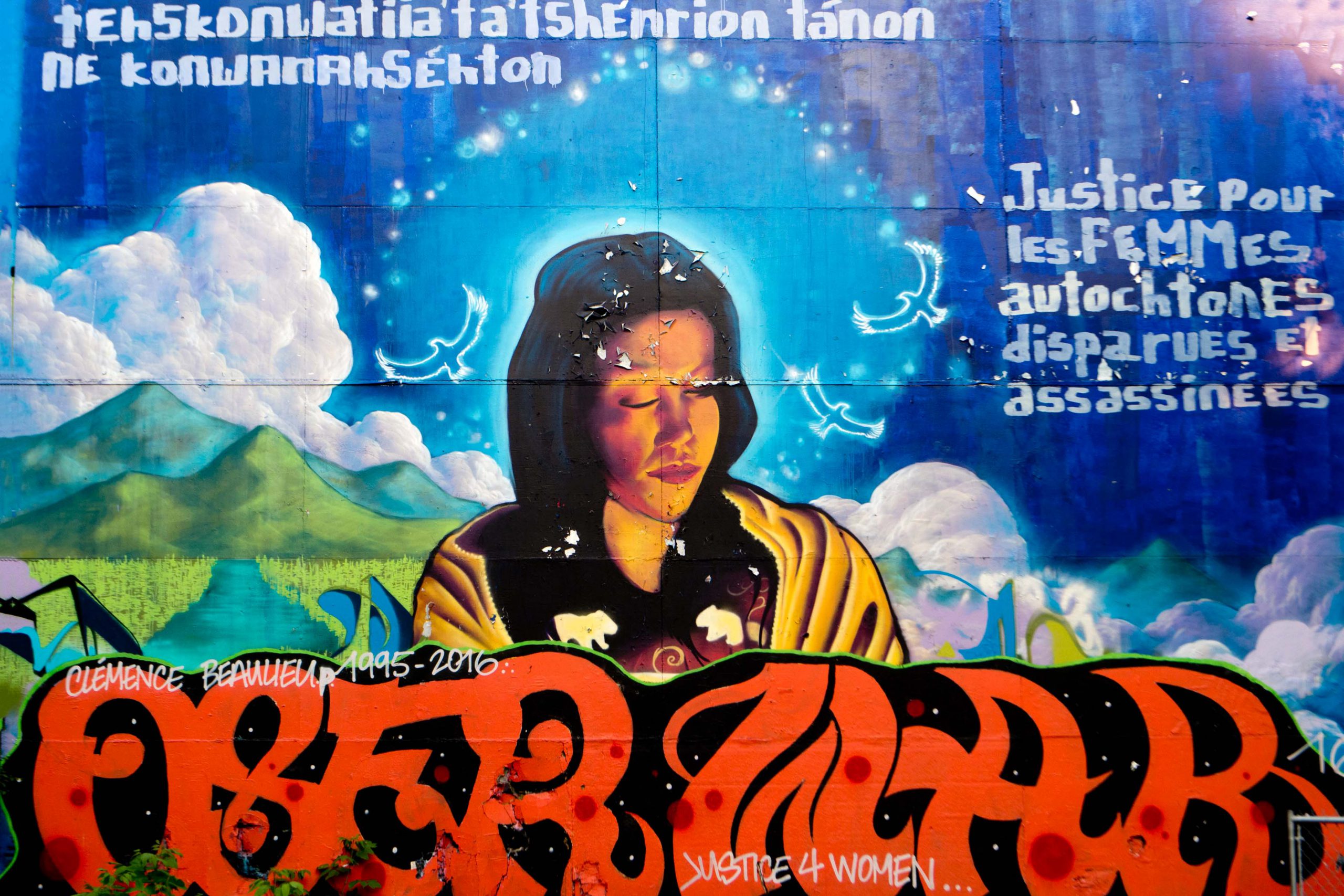

Patriarchy and settler colonialism

Patriarchy undergirds our life in Canada – a country premised upon the ongoing colonial dispossession of Indigenous peoples.

As Mi’kmaq lawyer Pamela Palmater has said, the historical “genocide committed against Indigenous women and girls [is because] Canada’s laws, policies and practices were both racist and sexist, which created this framework of violence”. Today, gendered colonisation manifests in interpersonal violence – Indigenous women and girls are disproportionately victimised by violent crime, homicide and human trafficking; economic violence – they are also overrepresented in statistics on unemployment, poverty, negative health and homelessness; and institutional violence – including high rates of child apprehension and incarceration, as well as coerced sterilisation and sexualised violence by police and corrections officers.

In a report released this summer on the situation in Canada, UN Special Rapporteur for Violence Against Women, Dubravka Šimonović, singled out the “inadequate protection of Indigenous women and girls” as a “major concern in the country”. She wrote, “Indigenous women from First Nations, Metis and Inuit communities face violence, marginalisation, exclusion and poverty because of institutional, systemic, multiple intersecting forms of discrimination not addressed adequately by the State.”

Patriarchy and women’s advancement

Patriarchy defines the terms and conditions of our “feminist progress”.

The integration of Western women into the capitalist workforce has been made possible through the simultaneous dispossession of another class of women: migrant caregivers. Since the early 19th century, Canadian immigration programmes designed to fill “care gaps” – ie to feed and care for children, the elderly and people with disabilities, so that their care givers could work outside the home – engender precarity among the workers whose entry into Canada they enable.

Primarily non-white women from the Global South, migrant caregivers are effectively tied to their employers in order to meet Permanent Residence (PR) eligibility and pursue family reunification. This creates conditions for widespread mistreatment and abuse. In their 2018 report Care Worker Voices for Landed Status and Fairness, a coalition of organisations dedicated to migrant worker justice document some common realities: long grueling hours; low and unpaid wages; lack of enforcement of minimum labour standards – including inadequate rest periods, a lack of privacy, inability to take sick leave and the inability to have a personal life; poor live-in housing conditions and prohibitively expensive options for independent living; sexual violence and harassment; and dangerous working conditions. As the report notes, “the current programme makes it impossible for most … to leave bad jobs”.

Related article:

Further, on average, migrant care workers applying for PR face an average of six to eight years of family separation. As the report notes, these years of separation can permanently damage and even sever familial relationships; 95% of those surveyed reported family separation as one of the biggest problems.

The migrant caregiver programme exemplifies the double-standard underlying dominant feminist impulse: specifically, that feminist advances should only apply to certain women. The migrant workers whose household labour enables Canadian women to ascend the capitalist hierarchy are, themselves, on its lowest rungs. Those tasked with caring for the children and parents of others are prohibited from caring for their own, separated by long family reunification processes. Those who support the well-being of people with disabilities are, themselves, deemed undeserving of such support, excluded from PR eligibility if their care needs are deemed too onerous for the state.

Misogyny beyond massacres

In our world order, we are invisibly connected to one another across vast geographies. Our lives are produced through the expansive moving parts of a global economy that are not always obvious to us – we typically do not have to confront those who sew our clothes, harvest our food, mine for the resources that make up our iPhones. We likely do not know those women who bear the brunt of our carbon emissions; those who are killed through our government’s international deals; and those against whom violent theft of land has been the prerequisite for our life in Canada. We do not know all the women whose non-consensual sacrifices finance our well-being and progress.

But our ignorance does not excuse our impact. We are made to be ignorant precisely because this ignorance enables the perpetuation of our world order – a world order that distributes well being and power along gendered lines for the elite few.

While interpersonal violence against women/femmes is one particularly obvious outcome of our global system of gender-based hierarchy, it is but one manifestation of the normalised dehumanisation of the majority of the world’s people. Normalised patriarchy operates precisely by rendering itself invisible, even as it has particularly noxious effect. Because the most pervasive forms of gendered violence are not those in contravention of social norms but those in perfect adherence to them. Gendered violence is not just interpersonal, but structural; not just physical but material; not just intimate but distant; not just illegal, but, often, perfectly legal.

Related article:

Among the perpetrators of gendered violence are those who are not behind bars and have never used their own fists.

Addressing violence against women and femmes means working for a world without femicidal murderers like Marc Lepine. But it also means expanding our definition of violence to encompass all of the sources of harm to women/femmes. Ultimately, creating a world that is not financed by the exploitation of the majority of the world’s people is the real task at hand. This means working in local and global solidarity for economic, migrant, environmental, Indigenous and racial justice, and for a world without war and colonisation.

Thankfully, women/femmes and their allies, here and around the world – particularly those who are Indigenous, Global South, immigrant, trans, gender non-conforming, disabled and otherwise marginalised – are already leading this work. They are fighting for the rights of migrant and Global South workers, resisting the construction of environmentally-destructive pipelines on stolen land, demanding a decent minimum wage and protesting war. Let’s not wait for 6 December 2020 to join them.

This article was first published by Roar Magazine.