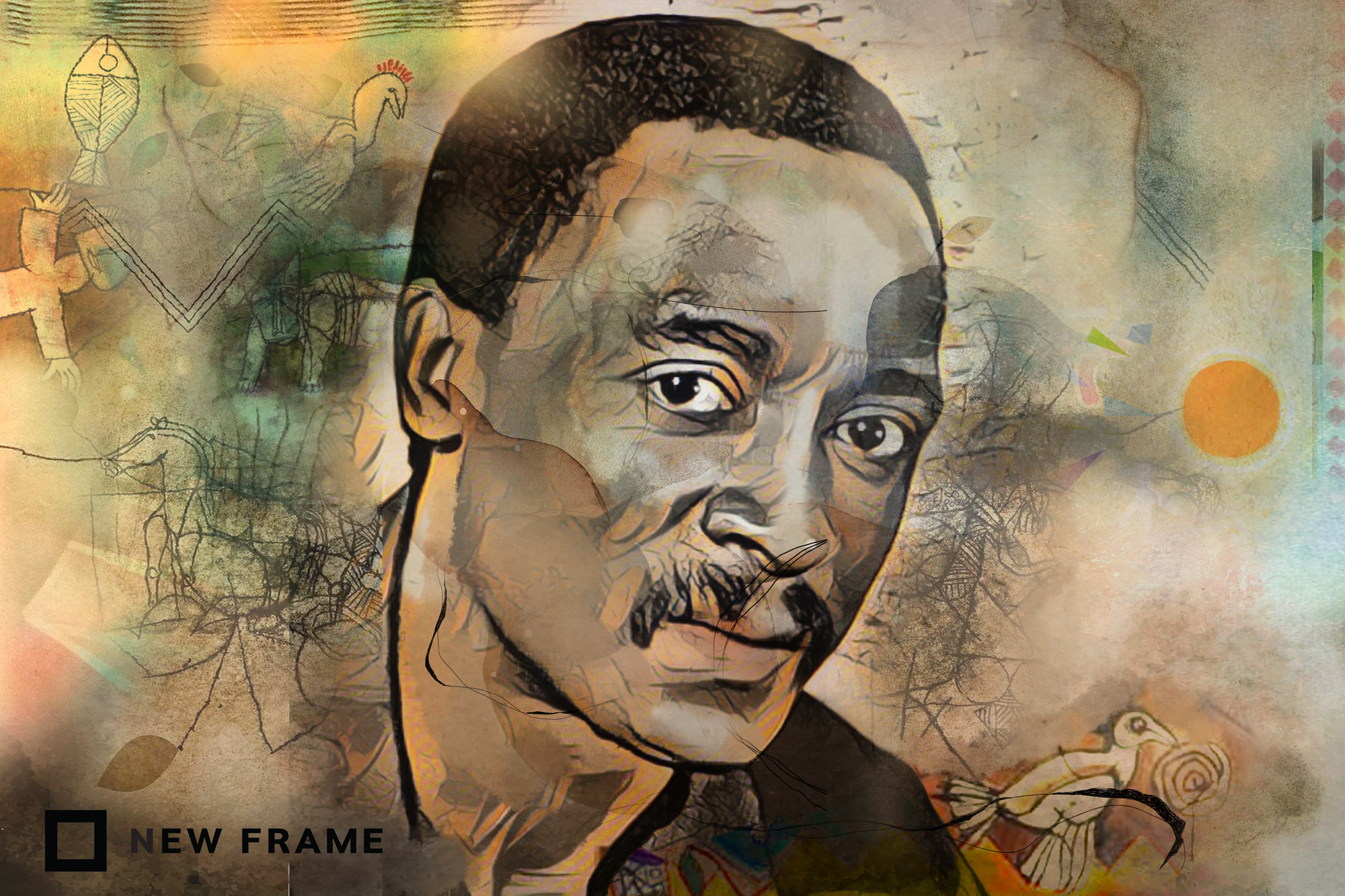

The evolution of Louis Maqhubela’s modernism

The artist went from township iconography to expressing ideas rather than observed events. He leaves a legacy of magical works that go far beyond the art of a life in exile.

Author:

2 February 2022

Louis Maqhubela died from Covid-19 in England on 6 November 2021, just days after his wife Tana had also succumbed to the virus. He was 82. A significant name in the canon of South African modernists who emerged during the apartheid era in the 1960s, Maqhubela went on to find his own unique form of abstract expression outside the country after leaving in 1978.

Although Maqhubela made several trips back to South Africa after 1994, including a 2010 visit to attend the opening of a major retrospective exhibition at the Standard Bank Gallery, his face and public persona were rarely seen here. While it knew his work, some of his early history and auction record, the South African art world paid criminally scant attention to his career outside the country, which spanned over four decades.

It was left to the Maqhubela family to make critics and journalists aware of his death. In a statement, they said: “Dad was as determined as he was kind and loving. His legacy in contemporary art is significant and he has impacted many lives in a positive way.”

Related article:

Louis Khehla Maqhubela was born in Durban in 1939. When he was 10 years old, his parents moved to Johannesburg. He and his sisters were sent to live with an aunt in Matatiele in the Eastern Cape before they rejoined their parents in 1952 and settled in Soweto.

While still a teenager in Soweto, Maqhubela was part of artist Durant Sihlali’s influential weekend artists group. He furthered his studies under the tutelage of Cecil Skotnes and Sydney Kumalo at the legendary Polly Street Art Centre in Johannesburg.

Maqhubela left school to become a commercial artist, and soon found himself taking on commissions to create paintings and mosaics in hospitals, schools and halls in Soweto. Skotnes helped secure him a significant commission to paint four large-scale public building oil works in 1961, only one of which, Township Life, has survived.

Art critic Marilyn Martin, a longtime champion of Maqhubela, wrote that the work “demonstrates a vitality, rigorous draughtsmanship and the use of strong non-descriptive colour and expressionist paint application that distinguishes it from the more stereotyped impressions of township life popular at the time”.

Widening his horizon

In 1966, Maqhubela became the first Black artist to win first prize in the Adler Fielding Gallery’s annual Artists of Fame and Promise exhibition. It pushed him to the forefront of a small but growing number of Black South African artists who were finding popularity among the critics and buyers of apartheid’s white art world.

The prize included a return air ticket to Europe, and the three months he spent there would have an indelible impact on Maqhubela’s philosophical outlook and artistic practice in the years to come. He saw the works of modernist and abstract luminaries such as Picasso and Paul Klee, whose vividly coloured figurative abstractions made a lasting impression on the young painter.

When he was offered a chance to meet perhaps the most celebrated living painter of the era, Francis Bacon, he turned it down, choosing instead to visit South Africa-born artist Douglas Portway at his home in Cornwall. Portway, who had left South Africa in the 1950s, had by this time established himself as a respected member of the British abstract movement. He and Maqhubela found in each other kindred spirits – both interested in expressing through their art “creativity and expression beyond observed reality”.

Related article:

Maqhubela would later acknowledge that he had learnt a lot from Portway, and his own work would become significantly influenced by his search for spiritual meaning, which he had begun to find in the teachings of the Rosicrucian Order, a community of mystics.

From the late 1960s onwards, Maqhubela’s style evolved to leave behind township iconography and figurative expressionism. Instead he favoured works that tried to convey feelings and emotion rather than resemble observed surroundings.

In the 1970s, this new style took root in distinctive, colourful abstractions. Martin described them as “thinly applied layers of paint articulated by means of sgraffito, sometimes completely abstract, at other times with figures, birds and animals emerging from the wiry lines, colour and floating shapes”.

Maqhubela told Martin in an interview that he also saw his adoption of abstraction as “a declaration of war against being stereotyped, bearing in mind that abstraction has, for centuries, been Africa’s premier form of expression”.

Life in London

Although he enjoyed a good measure of success despite the limited opportunities available to Black South African artists under apartheid, the oppressive nature of life under the regime proved too difficult for Maqhubela and his family. They left the country for good in 1973. They first settled on the Spanish island of Ibiza, famous at the time as a bohemian paradise for European artists, and in 1978 moved to London, where they would remain for the rest of Maqhubela’s life.

In London, Maqhubela furthered his studies at Goldsmiths college and the renowned Slade School of Fine Art, where he began to incorporate printmaking into his practice and produced a series of etchings that, according to Martin, “count among the most significant in his oeuvre”.

From England, Maqhubela continued to exhibit extensively in South Africa and his works were also increasingly visible in international galleries and shows.

Related article:

London gallerist Kapil Jariwala, who was a close friend, noted in a statement released after Maqhubela’s death: “The strong vein of energy that runs through his work and the essence of Maqhubela’s art is the absorption of everyday life in the townships of his beloved South Africa [and] this autobiographical heritage [was] something that sustained him in his London studio.”

But, Jariwala said, it would be a mistake to categorise Maqhubela’s work as simply the “art of an exile – someone looking for the past and alienated in his adopted country. Nothing could be further from the truth. He thrived in the London art scene where he was positively welcomed, recognised and supported by the most eminent collectors and artists with whom he forged meaningful dialogues and friendships that endured until the end.”

Arts patron and entrepreneur Vanessa Branson recalled how Maqhubela had two exhibitions at her gallery between 1987 and 1989. “Walking into his studio to select the works was akin to stepping into a cathedral of stained glass. The paintings all shimmering like stained glass windows bathed in light. My respect for Louis, for his quiet intelligence, knew no bounds. I even named my son after him.”

Renewal and retrospection

In 1994, Maqhubela made his first trip back to South Africa to “experience the euphoria of freedom first-hand”. Martin notes that this trip, together with a later return for medical treatment in 2001, gave “renewed impetus to his work, bringing thematic and technical changes”.

Maqhubela remained based in the United Kingdom, but his work was increasingly purchased for the collections of major institutions in the United States, UK and South Africa over the decades following the democratic transition in his homeland.

A Vigil of Departure, a major retrospective curated by Martin in 2010, showed at the Standard Bank Gallery in Johannesburg, the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town and the Durban Art Gallery. This served to rightfully return Maqhubela to his important place in the history of South African art. It also introduced the wide variety of the work that he had produced over a half-century to a new generation.

Related article:

As Martin noted, Maqhubela had no immediate successors “in the stylistic sense: his art was perhaps too personal and private, too enigmatic to emulate, but – understanding that there was a world beyond the immediate and visible and that it could be revealed through art – he served as a source of inspiration for his compatriots and artists everywhere”.

This is a sentiment echoed by Jariwala, who believes that Maqhubela’s work was influenced by “the accumulation of all his experiences”. The artist “produced magical paintings that belong in the here and now – they were as relevant in London as much as they were in Johannesburg or in New York – in fact to the whole world”.

A memorial service for Maqhubela and Tana was held in London on 15 December and his ashes are due to be returned to South Africa at a later date. The couple are survived by their three children and several grandchildren.