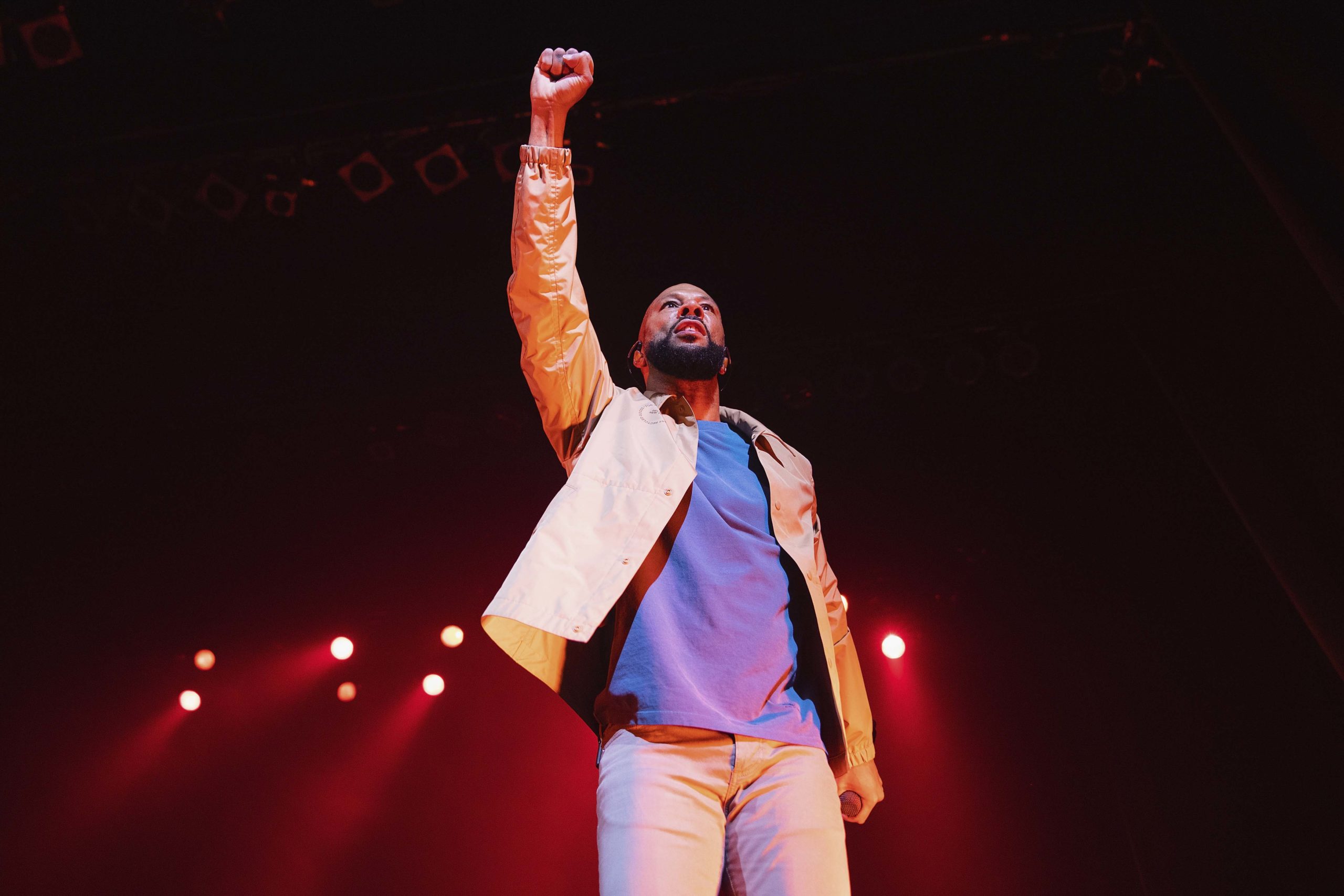

The evolution of Common

The veteran emcee from Chicago is finally getting his dues with a series of albums inspired by the struggle for racial justice. But his political ambiguity endures.

Author:

25 November 2021

It has become a trend for veteran emcees to spend a significant amount of time before a microphone when delivering freestyles. Black Thought, the emcee and co-founder of legendary hip-hop band The Roots, set the standard in 2017 when he rapped for 10 minutes straight on New York radio station Hot97’s Funk Flex Show. In the era of YouTube, in-depth freestyles have resurged as markers of stripes earned and talent shown.

Black Thought’s freestyle was a clarion call to his generation of rappers to return to basics and guard hip-hop’s founding principles: “Things fall apart when the centre is too weak to hold.” No one was better positioned among rap’s living greats to heed that call than veteran Chicago emcee Common; Thought’s lyrical sharpness became critical to The Roots’ success around the time that Common became mainstream hip-hop’s prominent disrupter. The two recently collaborated on Common’s Say Peace single and for many rap fans it has been a joy to watch their brotherhood grow.

In a recent appearance on Los Angeles station Power 106’s hip-hop show LA Leakers, Common responded to Thought’s call by delivering his best freestyle in years. Unlike his peer, Common has endured accusations of being a sub-par emcee for years, but has carried that belligerence with the maturity of a veteran. His freestyle was personal, essentially addressing the question of his ability to deliver.

Online publication Ambrosia For Heads called it a resurrection. But the headline – “Common resurrects his place as a top MC with this freestyle” – is telling. It reveals how little hip-hop, and the music industry at large, thought of Common.

“Forever signed to the art form, though things didn’t start warm,” Common raps in reference to his harsh beginnings and his struggle to gain recognition, unlike many of his contemporaries.

Laying a path

Younger hip-hop fans might struggle to understand the relevance of an emcee with fewer than five No. 1 albums. But Common’s continued defiance of mainstream expectation and his longevity in an industry that disposes of stars faster than it illuminates them cannot be overstated. He belongs to a rare group of emcees who are willing to sacrifice themselves for their art. They are not necessarily at war with the record industry or opposed to hip-hop’s commercial strides, but consider altering their sound for mainstream demands as a form of death.

Would Kendrick Lamar be able to do what he does in the absence of Common’s path? Lamar counts Dr Dre and Tupac as his primary hip-hop predecessors, but it is because rappers like Common spent years attending to hip-hop’s soul sensibilities that younger rappers like Lamar can test the possibilities of their craft with near absolute freedom.

Common was one the few emcees in the early 1990s who defied hip-hop’s growing role as a vessel of hyper-consumerism and crass materialism, and clung to what they considered their “authentic” voices. He has always acknowledged his contradictions, though. “I’d be lying if I said I didn’t want millions. More than money saved, I wanna save children,” he raps in The 6th Sense on his fourth studio album Like Water for Chocolate, which is considered his magnum opus.

For years, Common existed as a progressive pariah. This was partly because although his music is made for rallies and political discussions, in real life he still appeared to be wading through ideologies to find his political footing. This album, released in 2000, won Common reverence among Black progressives. It sounded like the work of someone who had finally found his voice and ideological framework.

He settled for political ambiguity on Like Water for Chocolate. His praise for exiled freedom fighter Assata Shakur in A Song for Assata is a standout. It dragged her out of obscurity at a time when she was taboo in mainstream hip-hop. Common’s album showed that he could embrace radical politics and continue to be a favoured emcee.

Top of the charts

Common has become less radical over the years, especially as he embraced more mainstream roles as an actor. He has spoken about how his desire to act demanded that he forgo aspects of his image as a rapper – and perhaps his politics – to be taken seriously. He embraced ideas of Afrocentricity about shared cultural identity, which earned him the respect of those who claim to have progressive ideals, but even that seems to have become more negotiable over time.

Common’s run with the now defunct Relativity label – releasing Resurrection in 1994 and One Day It’ll All Make Sense in 1997 – earned him cult status. It was during this time that his case for a brand of hip-hop in tune with its roots was strongest.

Related article:

After a strong showing at MCA Records with Like Water for Chocolate, Common signed with Good Music in 2006. His run with the label would mark the most successful period of his career, during which he made three consecutive Billboard No.1 charting hip-hop albums: Be in 2006, Finding Forever in 2007 and Universal Mind Control in 2008.

This success came about because although Common spent years earning his progressive and street stripes, he kept his music liberal enough to give it a shot at mainstream acclaim. To some, this is cowardice. They see Common’s political ambiguity as indecision.

The elasticity of Common’s music would eventually be rewarded – depending on which side of hip-hop’s ideological divide you stand – with an invitation from former first lady Michelle Obama to the White House in 2011. He joined a handful of rappers to boast of such a call and invited the wrath of America’s Right.

Memoirs and movements

As one of rap’s living elder statesmen, Common acknowledges that despite its progressive efforts, music alone is not enough to address some of the experiences that shape hip-hop culture. He does this in two memoirs, One Day It’ll All Make Sense (2011) and Let Love Have the Last Word (2021).

But the rapper is not a literary talent in the same way that he is a lyrical talent. And as with his music, his books reflect mainly his liberal world view. But he does write about personal issues that are relevant to broader hip-hop culture, such as being molested as a child. Musician Jaguar Wright accused Common in 2020 of sexual assault, an allegation he denies but one that requires a broader conversation about the routine failure of hip-hop (and the music and entertainment industries at large) to reckon with itself in this regard, even as it often serves as a vehicle for other political reflection.

The fatal police shooting of teenager Michael Brown in 2014 inspired a flurry of musical projects that sought to highlight the plight of Black people and the fight for racial justice in the United States. One of those projects was Common’s 11th studio album Black America Again. It was a return to the kind of social commentary that has come to define his music and pays special attention to two frontier movements setting Black America’s progressive agenda: Black Lives Matter and the prison abolition movement.

“I know Black Lives Matter but do they matter to us? The new plantation, mass incarceration,” he raps in a promotional freestyle on the popular Sway in the Morning show.

But with his affinity for liberal politics, that album was more an appeal to moral convictions – something Common does well – than a call to arms. After Black America Again, Common returned to collaborating and joined producer and jazzman Robert Glasper and drummer Karriem Riggins as the band August Green in 2016.

Understandably reluctant

Common’s 12th studio album Let Love lacks his usual social rumblings, but it solidified his place in the pantheon of veteran emcees still holding their own. Its maturity and lyrical depth was a feat critics and fans no longer thought he could achieve, given the pressure of getting a piece of the shrinking pie that is hip-hop’s mainstream audience.

It has come to be expected that Common will wax lyrical about Afro-optimism and unity on every new album. And he doesn’t disappoint on recent offerings A Beautiful Revolution (Pt. 1) (2020) and A Beautiful Revolution (Pt. 2) (2021). They are classic Common.

Related article:

Like most liberals, he sees the material accumulation of Black elites as communal progress or sufficient conditions for freedom. He isn’t necessarily interested in ending the structures that make much of that progress possible. A more radical and consistent interrogation of these structures and the anti-blackness that undergirds them would upend his liberal identity, so his reluctance is understandable.

A decade ago, it would have been easy to defend Common’s political ambiguity as the act of someone who has not quite found his political footing. But he has been around long enough now to know the limitations of liberal Black politics.