The dangers of street justice

Vigilante groups formed during the recent riots are testament to the state’s failure to protect its citizens. But self-defence can spiral out of control, harming people and fuelling paranoia.

Author:

3 August 2021

During the recent sabotage and rioting in KwaZulu-Natal and parts of Gauteng many people turned to informal policing. Some residents formed human chains around malls. Across KwaZulu-Natal, people guarded their homes and property with everything from paintball guns to cricket bats.

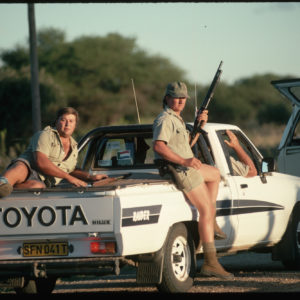

Private security forces formed temporary street militias with community watch groups and armed locals. These groups responded to a widespread failure of the state to provide security in a social crisis. In many instances, communities attempted to organise purely for self-defence, and there are many examples of cross-racial solidarity in the midst of the chaos.

But there was also racial profiling and violence motivated by racism, as seen in incidents in which white suburbanites manning barricades interrograted or even shot at Black residents. More disturbing were reports of shack settlements being torched. In Phoenix, a township predominantly inhabited by Indian people, 16 people are alleged to have been killed, some by vigilantes. Multiple people have been arrested for the killings.

Related article:

Evidence of a destablisation campaign, allegedly orchestrated by supporters of the jailed Jacob Zuma, complicates the issue of vigilantism. The campaign targeted infrastructure, co-ordinated home robberies and used social media to inflame racial tensions between Africans and Indians.

While evidence has emerged that vigilante violence certainly took place, other lurid stories, such as claims that a man dubbed “Rambo” was murdering innocent bystanders in Durban, have been exposed as fake.

Complex history

South Africans are still struggling to comprehend the full scale and timeline of the turmoil, and it is too early to tell if this will fuel racial paranoia and a turn to mob justice.

Vigilantism, where individuals or groups take it upon themselves to act as law enforcement, has a complex history in modern South Africa. Although townships were heavily policed during apartheid, little investment was made into protecting people from both criminals and brutal police officers. This forced some residents to create forms of self-government, such as street committees.

During the insurrectionary politics of the 1980s and early 1990s, these bodies resisted the state while also attempting to police issues of crime and interpersonal conflict in townships and shack settlements. As with the recent street militias, this took divergent forms. While there were examples of democratic approaches to security, there was also dangerous paranoia about informants, which led to necklacings.

Related article:

As Khanya Mtshali wrote in 2019, different forms of vigilantism have flourished since the end of apartheid. The government’s failure to address the social roots of crime makes people feel they need to take the law into their own hands. In response to the scourge of gender-based violence, “digital vigilantes” sometimes use “extralegal” means to expose past abuses online. Other groups focus on their immediate communities, patrolling their streets to discourage break-ins and to retrieve stolen property. But an atmosphere of paranoid fear can result in terrible violence, such as when xenophobia is legitimated by claiming “foreigners’’ bring crime and narcotics into the country.

While vigilantism is rooted in the fear of crime it can easily descend into its own form of mayhem. People Against Gangsterism and Drugs (Pagad) formed as a popular, religious-inspired movement against the narcotics trade in the mid-1990s. But Pagad, and in particular its miltant “G-Force” wing, quickly lost restraint and began performing public executions of drug dealers and planting bombs at gay bars, synagogues and even at the homes of Muslim scholars who criticised their violent methods.

Breaking the law to uphold it

The term “vigilante” comes from a Spanish word for watchman, a social protector who looks out for the public while they sleep. Vigilantes break the law, but they do not see themselves as criminals. Rather, they imagine themselves as community members who are delivering justice when the state is incapable of providing security.

In many instances, the vigilante is seen as a heroic outlaw. In Japan, the 47 Ronin, samurais who defied the law in order to right a past injustice against their former feudal lord, are regarded as exemplars of personal honour and social obligation.

This fascination has persisted into modern popular culture. When comic book superheroes like Superman and Batman were created in the 1930s, they were initially depicted as vigilantes who were prepared to kill the corrupt and crooked. In Superman’s earliest comic book appearances, his foes included abusive spouses and corporate lobbyists.

There is an ambivalence to vigilantes, with some romanticised as figures of resistance against repressive authorities and landowners. But they equally inspire fear. These violent “avengers” could themselves turn on the communities they protect.

Related article:

Despite myths about noble heroes enforcing justice, the actual history of vigilantism is sordid. Many of the publicly visible vigilante groups today work outside the state for racist and xeno-nationalist causes, such as far-Right street gangs like the Soldiers of Odin who harass migrants in Europe.

In other instances, vigilantes work in tandem with state repression. In Tsarist Russia, the Black Hundred gangs colluded with police to organise pogroms against Jews and socialists. After the American Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan emerged to defend white supremacy, with authorities turning a blind eye to lynchings and other atrocities. In the 1980s, the apartheid government supported the Witdoeke – named for white handkerchiefs worn around the arm – in conducting armed attacks on communities in the Western Cape.

Even if they are not formally deputised to work for the security state, some vigilantes see themselves as an extension of the law. In the wake of the George Floyd protests in 2020, “Blue Lives Matter” vigilantes such as Karl Rittenhouse killed people in the name of defending the police and “law and order”.

Related article:

Of course, this does not mean that all extralegal community defence works for oppressive forces. During revolutionary upheavals, like the Paris Commune in 1871 and Spain in 1936, people were quick to form “vigilance committees” and worker militias to patrol the streets and defend their homes.

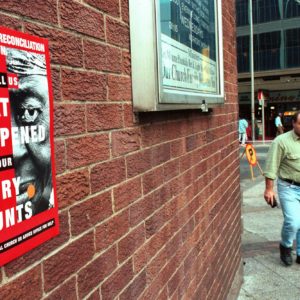

In response to the Ku Klux Klan, the Deacons for Defense and Justice defended Black communities and protected civil rights activists. This later inspired the Black Panther Party to institute armed “pig patrols” to guard against police violence. They even distributed “Wanted” posters to shame alleged killer cops.

More recently, women in India have organised against state indifference to gender violence by forming networks such as the Gulabi or Pink Saree Gang, which uses street patrols with bamboo sticks to intimidate and punish rapists and abusers.

Related article:

What separates these formations from right-wing vigilantes is in their different approaches to crime and disorder. Organisations such as the Black Panther Party saw social dysfunction and violence as a manifestation of greater structural evils that should be challenged and transformed. Rather than a malignant presence intruding from the outside, crime arose from existing social tensions and contradictions.

In contrast, conservative vigilantes see crime as an almost supernatural evil from alien forces separate from the community that must be purged through violence. Right-wingers see the world as starkly good and evil, and regard vigilantes, in the words of police historian Kristian Williams, “as saviours, as tough-talking, hard-hitting, no-nonsense, real-life Dirty Harry’s who will do whatever it takes to keep you and your family safe”.

Politicians and tabloid media are quick to mobilise around such a worldview, with figures like Donald Trump or Herman Mashaba presenting themselves as hardmen prepared to dispense spectacular violence – or what the political satirist Chris Morris called “gun-ishment”.

A progressive response to fear

The recent turmoil in South Africa will contribute to an increasingly paranoid and militarised social landscape. It certainly allowed racists a convenient opportunity to spew venom on social media, while white, far-Right influencers inflamed the situation by romanticising suburban militias as Spartan warriors defending their territory from imagined hordes, with one tweet using the ancient Greek phrase “molon labe”, which in English means “come and get it”, a popular term among the far-Right gun lobby.

Simultaneously, the sabotage and riots revealed the extent of privatised violence. Vigilante and criminal networks as well as the general paranoia of citizens mean many individuals own high-calibre firearms. Much of our politics it seems is still conducted in the shadows and expressed through brute force and violence.

It is imperative that all evidence of vigilante abuse and murders in all neighbourhoods be thoroughly investigated and exposed. As fake news stories are weaponised, getting the facts about the violence will help reduce the racial and class tensions that have been stoked in KwaZulu-Natal.

Related article:

The problem of vigilantism is compounded by the reality that the South African Police Service and the security state in general are clearly not going to deliver basic public safety, despite decades of attempts at reform. As a result, people will continue to turn to private forms of self-defence, from security companies to the more extreme forms of violence peddled by vigilantes or mob justice.

It is imperative that South Africans acknowledge both the severity of crime and the distorting social and psychological costs it imposes. Leftists can sometimes be too quick to dismiss crime as a product of socioeconomic ills, which obscures the reality of fear and how it plays out culturally and emotionally.

If the Left does not offer alternatives for crime control and community safety, the Right will. As Williams writes, fear creates a space for the right wing to monopolise the issue, using “crime” as code for “poor and Black”. It makes it easy for “conservative politicians to conflate real fears of violence with their own agenda in defense of economic and racial inequality”.

Alternatives may entail exploring new forms of both state-sponsored and community-initiated crime prevention. In a situation where formal state responses to crime have failed, private citizens will engage in self-defence. But this may result in an even more segregated and fortified society, where communities are pitted against one another in a race to the bottom.

Legitimate community protection must be distinguished from destructive and reactionary vigilantism. But building alternative forms of public safety cannot be achieved through theoretical speculation or policy papers. It must be rooted in existing experiences of struggle and activism that address the material and political roots of the South African nightmare.