The courage and catharsis of Tracey Rose

The artist’s retrospective, Shooting Down Babylon, presents a wide-ranging body of work that demands both quiet contemplation and a macabre sense of humour.

Author:

13 April 2022

Shooting Down Babylon, the largest comprehensive retrospective of the revolutionary work of Tracey Rose, who was born in South Africa in 1974, currently showing at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA), is a triumph. Over the course of her 25-year career, Rose has worked with film, sculpture, photography, performance, print, painting and multi-layered participatory elements, and after years of being able to access only snippets of her oeuvre online, seeing Rose’s incredible range in one place is a boon.

The show was initially intended to open in 2020 but was pushed back because of the pandemic. After such a long delay it is a relief to see the show finally happening. Its robust programming and deep engagement in the exhibition space is also reassuring. A two-day symposium in June 2022 is planned to mark the launch of a 400-page monograph on Rose’s practice, including contributions from Adrienne Edwards, Khwezi Gule, Kellie Jones, Gabi Ngcobo and Simon Njami.

Related article:

At the press preview the day before the opening on 17 February, Zeitz MOCAA chief curator Koyo Kouoh said of the exhibition: “It is a luxury we deserve.” This retrospective is a timely reminder that success often feels like relief. National celebration of Tracey Rose’s international success is long overdue and brings up the difficult question: how many Black South African woman artists have had career retrospectives at home? Poet and scholar Gabeba Baderoon reminds us that what we choose to display in public spaces and “who becomes visible to us in art represents a national conversation about who ‘we’ are”. This makes the retrospective an important form. Its purpose is to offer not only an exposition of developments in the artist’s body of work, but also an opportunity to reflect on their contribution to the field, to situate the artist in a broader imaginary.

Art critic Linda Yablonsky has queried the criteria for mid-career retrospectives, asking, “Is it the breadth of their accomplishment, the number of collections that include them or how many times they get their names in the paper? Is celebrity the new measure of value? Or is a curator’s faith enough?”

In this case, it is all of the above.

The makings of a moment

Kouoh described Shooting Down Babylon as “a historic moment, an emotional moment” and a long-dreamt-of moment to celebrate her “sister, friend [and] collaborator, an artist who matters”. The two met in 2000 at Dak’Art, the long-established biennial in Dakar, and since then, Rose has made numerous appearances in exhibitions Cameroonian-born Kouoh has curated.

The joyous fact of years of companionship and kinship between curator and artist bears fruit in this exhibition. A 2020 Artnews article profiling Kouoh’s new position as executive director and chief curator of Zeitz MOCAA sheds light into their relationship: Rose describes Kouoh, one of her son’s godmothers, as family. Of Kouoh’s unwavering support she says: “When you work with her, she’ll fight for you in a way that a lot of other art-world people won’t.” Curator Nkule Mabaso says, “The miracle is, in fact, that, given the overwhelming odds against women, or Blacks, so many of both have managed to achieve so much sheer excellence, in the face of violent, selective and shifting definitions of history and art, and in the face of direct suppression, omission, gatekeeping, lack of transparency and outright unprincipled opportunism of unscrupulous gallerists, and their ilk.”

Related article:

Kouoh’s insistence on in-depth solo exhibitions at Zeitz MOCAA is illustrative of her pragmatic support and ethical approach to curating. At the exhibition preview, she described solo exhibitions as “a space for knowledge transfer” and a welcome break from “the ubiquity of group shows, which essentialise African artists, especially along geographic lines”. Worse, group shows are often at risk of being grossly gendered and racialised, exhibiting what artist Reshma Chhiba and curator Nontobeko Ntombela describe as violence in curatorial frameworks, “reflected in the ways in which Black women artists’ work is presented through hackneyed terms like ‘identity’”.

Solo exhibitions and retrospectives are one way to concentrate on African artists, and women artists especially. They are an opportunity to engage the artist through multiple lenses, simultaneously learning from their practice and acknowledging the impact of their works.

Deliverance from Babylon

Rose shot to international fame soon after the end of apartheid as South Africa re-entered global cultural circuits, and much of her work has been powered by rage, an affective grammar to articulate her opposition to unjust systems and her frustration at expectations that she perform as an embodied apartheid retrospective. This exhibition feels like a productive place for that rage, a repository for meaning-making guided by Rose, the shaman.

The first room of the exhibition is spattered with pink paint meant to evoke blood. In the centre is the video installation from which the exhibition title is derived, Shooting Down Babylon (The Art of War) (2016). This work features scenes recorded from cameras attached to Rose’s body while she was performing dance rituals, in the background are the voices of people participating in an ayahuasca ceremony, a spiritual purification ritual from the Amazon. This is an invitation, perhaps even an invocation, for viewers to similarly pursue a spiritual journey through the immersive artworks, to cleanse themselves of a spiritually corrupt state known as Babylon in the Rastafarian religion, symbolising the debauchery, oppression and exploitation of the modern materialist world.

In the second room is The Kiss (2001), the famous photograph depicting Rose on a plinth as if made of marble sensuously draped across the lap of her then gallerist Christian Haye in a pose reminiscent of Auguste Rodin’s iconic sculpture of the same name. The photograph was made during Rose’s artist residency at Iziko: South African National Gallery, and staged inside the museum. At the time, curator Emma Bedford wrote that in The Kiss “the canons of conventional art history are imploded by substituting the marble-white bodies, those epitomes of aesthetic perfection, with bodies that assert their difference through a range of skin tones”.

This iconic work is followed by two lesser-known works, Whoremoans (2014), a difficult-to-watch triptych of graphic video works that Rose describes in the exhibition audio guide as the trailer of “a soon-to-be-made, or impossible-to-make, B-grade porn historio-narrative”; and White Girl Fart Factory (2015), which is inspired by the inventor of peanut butter George Washington Carver, an African-American agricultural scientist.

In the second installation, Rose connects this history to the South African context by drawing from the iconography of popular local peanut butter brand Black Cat. She invites viewers to eat cookies baked specifically to trace the entangled chain of so-called coloured labour and white consumption in the Cape. White women viewers were encouraged to take an empty peanut butter jar home and fart inside it and return the jar to the museum to complete the installation.

According to writer Zaza Hlalethwa, “A stillness is required to engage seriously with the work of Tracey Rose.” Indeed, this is an artist who problematises and dramatises everything from religion to sexuality. In her performances, investigations of spirituality sit snugly with the absurdity of race. But, as the White Girl Fart Factory reveals, a sense of humour is necessary. Rose says in an interview with Elephant magazine, that “there’s always been an underlying tension of humour” in her work, citing her 2005 piece San Pedro V: “The Hope I Hope” in which she urinates on the Israeli West Bank wall dividing Israel from Palestine while playing the Israeli national anthem on a guitar to “invite some kind of visceral reaction like awkward, uncomfortable laughter”.

Playwright Samuel Beckett once described writing Waiting for Godot (1952) as a way of finding “a form that accommodates the mess”; and Rose’s chosen form, performance practice often translated into or accompanied by photography, video, installation and digital prints, often involves using her body to do just that. As a visual motif, protest site and a vessel to transcendence, Rose’s body accommodates the mess by placing “the creative and the explicitly critical alongside one another”, to echo literary scholar Pumla Dineo Gqola.

The demands of the work

Experiencing this exhibition is therefore, understandably, a messy business. It demands both contemplation and a macabre humour to deal with the drama and trauma that has been spat, shat, sweated, endured, expressed, researched, released, vented and vomited over multiple decades and floors of the museum. Described as absurd, anarchic, slapdash and carnivalesque, Rose’s work accommodates and explores much, so moving along through this exhibition is akin to proceeding through an archive of crude, brave, incisive reflections of the status quo. Or as art historian Nana Oforiatta Ayim neatly summarises: “Rituals of revelation and rituals of reordering are what Rose offers: the uncovering and recalibration of histories of violence, of women’s often-unspoken presence in these histories, and of the limits and limitlessness of language and of these tellings, and through all this, the healing of some of the ruptures of self.”

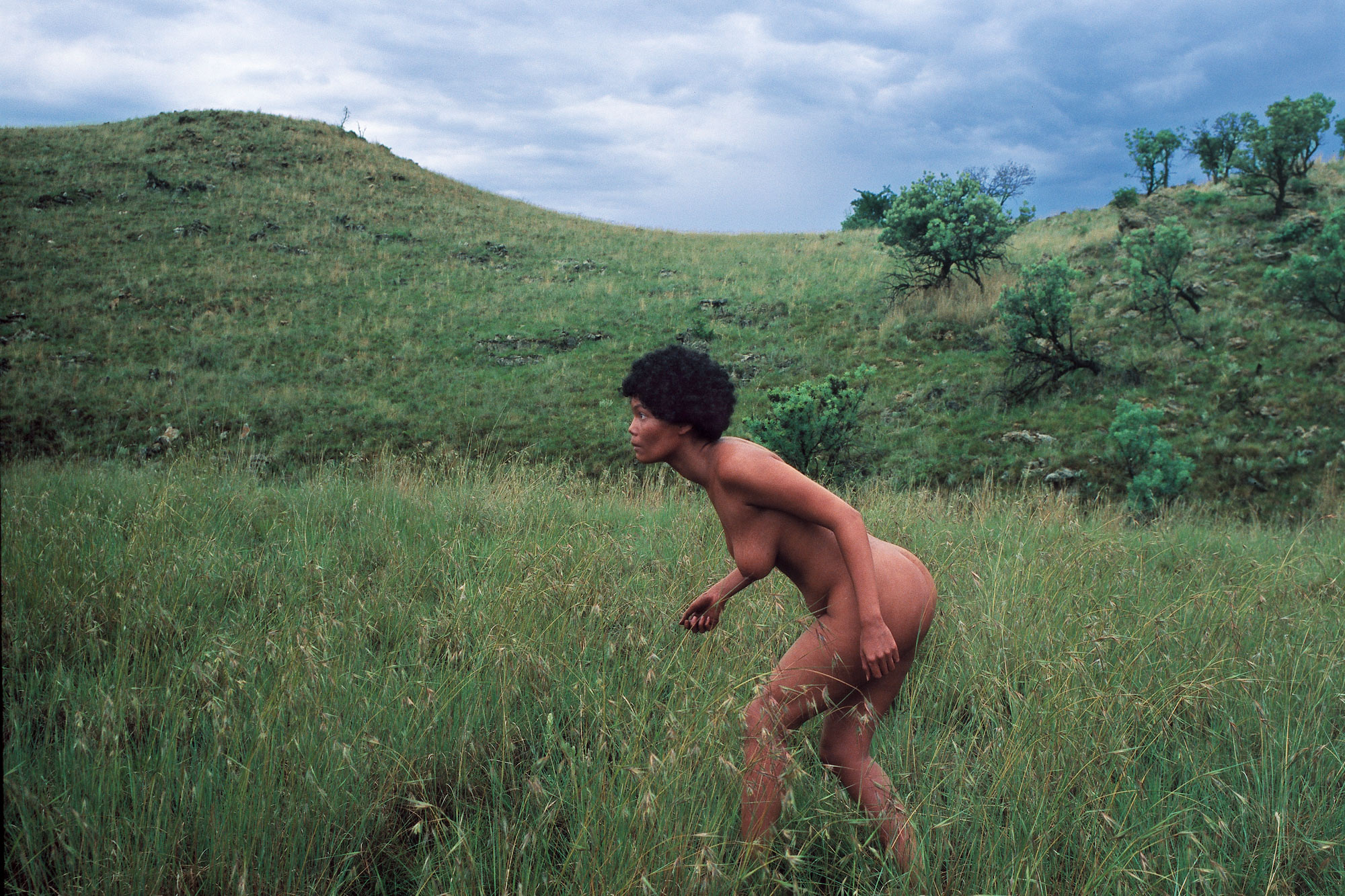

This is most evident in the glittery green gamut, host to one Rose’s major career milestones, Ciao Bella (2001), a three-screen video installation re-enacting the Last Supper, which features 12 real and fictional female characters, all played by Rose. We see Rose nimble as American-born French dancer Josephine Baker, decadent as a powdered Marie Antoinette, wading through lush green grass as Saartjie Baartman; stern as Catholic school headmistress Mami, horrific as Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, and more. This performative reimagining of female figures is prescient – she was already letting everyone in on her extensive range.

Art historian Jones has argued that Rose’s practice centres both writing and thinking. Curator Serubiri Moses discusses this art-as-thinking in terms of the multiple perspectives from which Rose’s performed identities can be viewed, her skill at portraying not only compelling characters but also communicating the complex ambiguity of multiple subject positions. Moses writes, “Like the work of feminist theorist Audre Lorde, who analysed class and gender-identity differences among Black women, Rose’s work shatters assumptions about subjectivity and knowledge. While Rose’s art challenges neat art-historical canons and disrupts assumptions about Black women in particular, we would be remiss to consider Rose a scientific thinker performing art-historical analysis or revision. This notion obscures the artist’s unique approach, which offers alternatives to thinking through subjectivity, knowledge and narrative. Rose tackles these philosophical topics using creative, fictional, playful and performative strategies.”

Aversion to didacticism

There are numerous strategies at play in this exhibition, and the intent behind them is not always clear. For instance, one room is filled with mixed-media double-sided drawings, described as “narratives of scripts that are yet to be released, stories told and erased”. Perhaps intended to document Rose’s process or hint at things to come, the room is reminiscent of Kara Walker’s 2021 exhibition of more than 600 drawings, A Black Hole is Everything a Star Longs To Be, but without the sense of epic proportion and thematic clarity.

At other times, the organising logic seems superfluous. Like the room including multiple parts displayed on separate walls: one wall is filled with delicate, pretty drawings, a collaboration with her son intended as a balm to the brutality of history displayed on other walls. Another is dominated by Tsafendas’ Head (2015), a monumental sculpture representing Dimitri Tsafendas, who assassinated former South African Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd, the “architect of apartheid”, in Parliament in 1966 claiming to be working on the orders of a tapeworm. In the audio guide, Rose describes Tsafendas as “the man with the tapeworm, the one we forgot, who died alone in Sterkfontein. No presidential pardon, no thank you. The man with the tapeworm in his head died alone, unrecognised, not knighted, thanked or acknowledged.”

Opposite Tsafendas’ Head is a rough rock face or cavern, scribbled with the names of slave communities in colonial Argentina as graffiti. In the centre is a portrait of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun, a reference to rumours that the couple moved to South America in 1945. Another wall features a painted double rainbow, layering historical references to Uruguayan artist Carlos Capelán’s persecution by Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet with Rose’s dedication to political prisoners. In the centre of the room is an inflatable rubber ball with a plastic penis attached to it, referencing the colonial practice of castrating Black men. This is one of Rose’s Mandela Balls, an ongoing project to create 95 balls that represent Nelson Mandela’s age at the time of his death.

Related article:

Is this room a reminder of the reach of Nazi movements outside of Europe, of Nazi influence on apartheid South Africa? An impassioned remembrance of a forgotten man Rose claims as hero? A saccharine nod to children as hope for the future? An ironic take on the entanglements between patriarchy and colonialism? Upon reflection, it is most likely an aversion to didacticism, demanding that viewers probe and decide on their own.

Rose is currently working towards a PhD at the University of the Witwatersrand, where she also teaches, and holds a BA in Fine Arts from the same university and a masters from Goldsmiths College, University of London. It makes sense that her work is deeply researched, revealing multiple systems of knowledge and methods of inquiry that, according to Rose, stem from exorcism and ritualistic art – healing that does not always make sense.

Her investigations into postapartheid legacies and liberation movements throw up questions about repatriation, recompense and reckoning that are not easily asked, never mind answered. As South Africa stumbles through the rainbow-nation fugue in which, to quote novelist Ivan Vladislavic, “a provisional country asserts itself, but drags its history behind it in brackets”, Rose renounces rote narratives.

Many works in this retrospective are testament to her refusal to accept things as they are, and not just in South Africa. The Wailers (2004), for instance, is a silent but evocative video of five Hasidic Jews playing basketball under water, a novel way to raise questions about the Jewish community’s identity and status in South Africa and globally. Die Wit Man (2015) documents Rose’s 7km walk through Brussels, chanting the name of Congo’s first democratically elected leader, Patrice Lumumba, through a plastic megaphone. Belgian agents tortured and killed Lumumba in 1961. Later, Gerard Soete, a senior Belgian police officer, exhumed his body, dissected it and then dissolved it in sulphuric acid.

Works like this show that to heal and grow, you cannot shy away from the realities of Babylon. To shoot it down, like Rose, you need to face it head on.

More than rage – which is there in spades – Shooting Down Babylon offers courage, catharsis and a sense of spiritual direction. As if through this exhibition, anger and alienation have coalesced into something incandescent and full-bodied and Rose has begun mapping a way to Zion, that elusive utopian place of unity, peace and freedom.

Shooting Down Babylon is on show on levels 0, 2 and 3 of Zeitz MOCAA until 28 August 2022. Viewer discretion is advised because of the show’s graphic content, which some viewers may find disturbing. This exhibition is not recommended for people younger than 16.