The controversial life and death of Paul Mushonga

The pioneering nationalist’s contribution to Zimbabwe’s freedom has been obscured by what is sometimes called “patriotic history”. He remains an unheralded pan-African icon.

Author:

29 January 2020

On 2 December 1962, Paul Munemo Mushonga died in a car accident, an early victim of what is known in Zimbabwe as the phenomenon of the “black dog”. The phrase came into currency in the 1990s following the death of outspoken opposition parliamentarian, Sydney Malunga. The MP died, so said his chauffeur, when he swerved off the road while trying to avoid a “black dog”.

Following Mushonga’s death at the age of 35, a Southern Rhodesian (colonial Zimbabwe) newspaper eulogised the anti-colonial nationalist and late president of the Pan-African Socialist Union (PASU), proclaiming, “When the political history of this country comes to be written, Mr Mushonga’s name will no doubt find a prominent place.” The accident received international coverage, with major British dailies like The Times running Mushonga’s obituary.

Almost 60 years later, however, Mushonga remains neglected in the historical memory of Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle. In post-colonial Zimbabwe, the state has pushed a one-sided narrative that focuses on the military struggle against the white-minority government. The resistance by individuals connected to the ruling ZANU-PF receive precedence over the sacrifices of others. The British academic, Terence Ranger, who lectured in Southern Rhodesia until he was deported by colonial authorities, famously termed this phenomenon “patriotic history”. Mushonga is the archetypal casualty of patriotic history’s bias.

Mushonga’s short but convoluted and dramatic political career capped by a death mired in controversy is largely forgotten today. In both life and death, however, he loomed large in Zimbabwe’s independence struggle.

At times, he appeared to be a skilled political operator, cultivating pan-African and anti-colonial networks in West Africa, Europe and North America with uncompromising revolutionary ardour. Equally, there were allusions that he was secretly backed by Rhodesia’s white settler government as a third force. He bore undeniable responsibility for laying the groundwork that enabled the internecine strife that emerged in Zimbabwe’s nationalist movement in the early 1960s and which resulted in the collapse of the unity that pan-Africanists cherished.

Sordid legacy of car ‘accidents’

Like a string of car-related incidents involving the deaths of prominent politicians in colonial and post-colonial Zimbabwe, Mushonga’s death was shrouded in mystery. Zacharias Mushonga, the nationalist’s youngest brother believed the death was the result of foul play. Zacharias insinuated that his brother’s closest political associates had been less than forthcoming about the circumstances surrounding the untimely death of the PASU leader. Conversely, Mushonga’s travelling companions all survived the crash with limited injuries and claimed that they had survived a government hitjob.

The spate of curious deaths involving prominent Zimbabwean politicians was inaugurated in August 1962 with the death of Tichafa Samuel Parirenyatwa, just months before Mushonga’s passing. Parirenyatwa was Rhodesia’s first black medical doctor and the vice-president of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), the colony’s most significant nationalist movement at the time.

While the official version of events has it that Parirenyatwa died when his car was struck by a train, his driver, Edward “Danger” Sibanda, who survived the incident, recalled being forced to stop by whites who then assaulted them. A government inquiry rejected these claims and charged Sibanda with culpable homicide. However, the transcript of an interview in the National Archives of Zimbabwe with Leo Baron provides a compelling defence of Sibanda’s declaration. Baron, who briefly served as Zimbabwe’s acting chief justice after independence, was tasked by ZAPU’s president Joshua Nkomo with conducting a private investigation into the incident.

Related article:

As colonial Rhodesia gave way to independent Zimbabwe, the car “accident” became an increasingly prevalent feature. In December 1979, just days after the constitutional agreement that would shortly usher in Zimbabwe’s independence was reached, Josiah Tongogara, a leading guerrilla commander died in a car crash in Mozambique. On the eve of Zimbabwe’s elections in 2013, a prominent opposition figure penned an opinion piece in the Huffington Post charging Robert Mugabe’s post-independence government with responsibility for a number of car ‘accidents’.

Mushonga’s rise

Mushonga came to prominence on Zimbabwe’s political scene in 1955 as a co-founder of the City Youth League, the political movement widely seen as inaugurating mass opposition to white rule. Like a number of early political activists, Mushonga came out of the Catholic missionary tradition, a background he shared with Mugabe. Mushonga was born in 1927 at the Chishawasha Mission just outside of Salisbury (today’s Harare). His secondary education was at Kutama College, where he followed Mugabe.

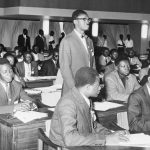

Mushonga (who had impeccable handwriting) was the League’s secretary. Following a merger in 1957, the League rebranded as the Southern Rhodesia African National Congress (SRANC). Alongside the independence of Ghana that year, the first territory to shed the burden of British colonialism in sub-Saharan Africa, the nationalist movement in what would become Zimbabwe appeared to be gathering pace in step with other liberation struggles across the continent. Mushonga and others worked assiduously to cultivate ties with international partners to advance their struggle.

Following the establishment of the SRANC, Mushonga remained in the political leadership, albeit in a slightly less senior position as vice-treasurer. However, he literally remained at the heart of the struggle. Pfumojena, the back room of the general store his family operated in Highfield, a Salisbury township, served as the SRANC’s headquarters. His father had been one of the first to open a store in the township’s retail centre, now known as Machipisa.

In the late 1950s, Mushonga’s international contacts deepened significantly, and he played a major role in internationalising the Zimbabwean liberation struggle.

In the first half of 1958, he attended the World Assembly of Youth Conference in Dar-es-Salaam, establishing contact with members of Julius Nyerere’s Tanganyika African National Union. That December, along with Joshua Nkomo, he represented the SRANC at Kwame Nkrumah’s All-Africa People’s Congress (AAPC) in Ghana where he encountered the who’s who of African political personalities (including Tom Mboya, Patrice Lumumba and others). Alongside future Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda, Mushonga prepared material for the AAPC sub-committee on racialism and discriminatory laws. On his return, he became close to another AAPC delegate, and future African head of state, when Hastings Kamuzu Banda, Malawi’s future President, lodged at Mushonga’s home during a layover.

In February 1959, he hosted a reception in his Highfield home for a visiting British Labour MP, John Stonehouse. Days later, Stonehouse was effectively deported from the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, a territory linking present-day Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi. The Southern Rhodesian government declared a state of emergency and jailed hundreds of political activists, including Mushonga and his wife. The SRANC was banned and a new phase of struggle was launched.

Enemy of the state?

Following this Emergency, Mushonga’s political career took a hazy turn.

His wife, Evelyn, was probably the only woman jailed at this time. Along with their adopted two-year-old son, she spent almost all of 1959 behind bars. She was eventually “paroled” to Driefontein, a Catholic mission outside of Mvuma, near Fort Victoria (now Masvingo), a town far from their Salisbury home. Her husband was not released until April 1960. Both were classified as political detainees and had not been convicted of any crime.

Records in the National Archives of Zimbabwe indicate that prison authorities found Mushonga to be a particularly troublesome character. An October 1959 report on the detainees accused Mushonga of “heading for trouble”, with the officer in charge adding, “I have on several occasions checked him on his behaviour.”

It was a surprise then, that just a few months later, Mushonga was discharged from the custody of the colonial government, ostensibly so that he could receive treatment for a kidney ailment in London. His Youth League co-founders, James Chikerema and George Nyandoro, remained under government restriction until early 1963. Curiously, Nyandoro, who suffered great pain from tuberculosis of the spine, was initially not granted a similar discharge for medical care abroad.

On 1 January 1960, a new political group, the National Democratic Party (NDP), was launched to fill the void following the SRANC’s banning. Its constitution was allegedly largely written by Edson Sithole, a young acolyte of Mushonga and a former Youth League member, who was then in detention. The document explicitly committed the party to promoting pan-Africanism and was significantly more radical in tone than the SRANC constitution, which pledged allegiance to the British monarchy.

Mushonga continued the struggle from exile. The NDP had established its first foreign mission in London, Mushonga’s new base. He was seen off on his flight to England by some 300 NDP supporters. Some of his last words in Rhodesia before enduring two years of exile were:

“The country is yours. You have no other place you can call home. I will be with you everywhere I go – in jail or in hospital. Don’t worry about me or my wife or my child. Only worry about your country. I know you are not cowards and that while I am away you will fight for what I have fought throughout my entire life.”

Related article:

According to a Rhodesian newspaper, at the conclusion of his speech, “the whole building reverberated with thunderous cries of ‘freedom now’ repeated by the crowd”.

Rhodesian authorities sought to keep him on a short leash. He travelled on a passport valid for less than a year and was required to deposit his return ticket at Rhodesia House, the government’s diplomatic post in London.

Initially, Mushonga kept a quiet political profile, although that August he joined with Garfield Todd, a former Rhodesian Prime Minister and several London-based NDP members to call on Britain to suspend the colony’s Constitution and impose martial law after the lethal unrest known as “Zhii” in Bulawayo.

It seems likely that bread-and-butter issues dominated Mushonga’s concerns. In addition to his wife and son, Mushonga had a number of dependents who were a source of anxiety. He was the eldest of four brothers (one of whom died while young) and also had two sisters. He also sought to quench the insatiable thirst of Sithole, still under government custody, for educational knowledge, paying for his enrolment in a correspondence course. A gift of several hundred pounds from Banda alleviated financial pressures considerably.

The demonstration of popularity at Mushonga’s airport farewell belied his declining formal role in the nationalist movement, however. Mushonga was one of the most vociferous voices criticising Nkomo in early 1961. The NDP leader had initially assented to a new non-democratic constitution at deliberations convened by the British. Amid allegations that he was unhappy with the NDP and contemplating launching a new party, it was reported that Mushonga had finally been offered a formal position in the NDP’s London Office, nearly a year after his arrival in the city.

Leadership of Pasu and the Zimbabwe National Party

Rumours of Mushonga’s lingering discontent proved prescient. His new role as second secretary of the NDP’s London office constituted a significant loss of status for an individual who was arguably one of the colony’s three most prominent nationalist politicians only a few years earlier.

In June 1961, Zimbabwe’s nationalist movement experienced the first of several splits that would plague the struggle against white minority rule. Mushonga became vice-president of the new Zimbabwe National Party (ZNP), which dismally failed to dislodge the NDP from its pre-eminent role but gave it a scare for several months in mid-1961. Although it has largely been forgotten in accounts of Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle, the ZNP had significant star power.

Its secretary-general was Michael Mawema. As the first President of the NDP, Mawema is credited with giving ‘Zimbabwe’ its name. The ZNP president was Patrick Matimba, who, despite low levels of formal education, was known as a suave, articulate speaker, notorious for his marriage to a Dutch woman at a time when it was illegal for black men to engage in sexual relations with white women in Southern Rhodesia. When the ZNP was formed, the government still held 14 high-profile members of SRANC, originally jailed during the emergency declaration. Eight of them (including Sithole) came out in support of the ZNP.

The split was at odds with the prevailing emphasis on pan-African unity at the time but ZNP supporters sought to buttress their position by observing that continental luminaries like Kwame Nkrumah and Kenneth Kaunda had led breakaway parties during their struggles for national liberation. The party earnestly courted pan-African backing and Mushonga undertook a tour of west African capitals around the end of the year.

Mushonga continued to be based in London when the party was launched. He thus escaped a violent assault on Matimba and Mawema by NDP supporters that forced the ZNP to cancel the party’s formal launch programme. Within a few months Mawema dropped out of the party and tensions flared between Mushonga and Matimba. The latter was widely seen as a political opportunist. He was subjected to much suspicion as he had been deported following the emergency on the understanding that he reside with his wife in Europe. For the general public, it was unclear what had changed when Matimba was allowed to return to Rhodesia to build up the ZNP.

Related article:

In mid-1962, news leaked that Matimba had engaged in talks with Moïse Tshombe, then the leader of the secessionist Katanga Republic in the former Belgian Congo. Tshombe was implicated in the assassination of Lumumba, the Congo’s popular Prime Minister. He was reviled and widely perceived as beholden to neo-colonial interests. At the time, Matimba and Mushonga were attending a conference of nationalist leaders in Ghana and were expelled from the country.

This disgrace marked the end of Mushonga’s commitment to the ZNP. On 17 September, he launched PASU. Timothy Scarnecchia, a professor at Kent State University, has written of rumours that the party was cultivated by Abe Abrahamson, Southern Rhodesia’s Labour minister. Scarnecchia quotes a dispatch from the US consulate in Salisbury which reported allegations that liberal elements in the Rhodesian government desired PASU’s participation in forthcoming elections to improve the government’s image.

While the context behind PASU’s emergence remains unclear, the timing of PASU’s launch was curious. On 20 September 1962, ZAPU, founded days after the NDP was banned in December 1961, was itself proscribed by the Southern Rhodesian government.

Quite abruptly, and just days into PASU’s existence, Mushonga found himself leading Rhodesia’s only legal black political party with a degree of respectability. Elections were just months away, the first under a new Constitution with an expanded parliament expected to feature 15 black parliamentarians, the colony’s first black MPs.

After an exile of more than two years, Mushonga returned to Salisbury from London on the last day of September 1962. His reception at the airport upon his return was notably smaller than that which had seen him off. Nevertheless, the papers reported that 100 PASU supporters welcomed him.

Striking a confrontational tone, Mushonga declared that the new Constitution “can only be implemented over our dead bodies”, an eerily prescient proclamation; elections were held less than two weeks after Mushonga’s death with no PASU participation.

The boycott surprised some political commentators, but Mushonga never gave any indication that he supported PASU participation in the election. In his last press conference, five days before his death, Mushonga urged all black candidates to withdraw from the election and made a call for unity in the nationalist movement. If Abrahamson’s alleged support of PASU was with the understanding that the party would contest the forthcoming election, he was sorely disappointed.

Toward the end of October, Mushonga travelled to New York and delivered a fiery speech at the UN. He attacked the Federation’s Prime Minister, Roy Welensky, accusing him of working in an “unholy alliance” with apartheid South Africa and imperialist Portugal. By the beginning of November, reports suggested that PASU had built a membership of 8 000 and the party was promoting scholarships and travel opportunities it had secured for students.

However, Mushonga had by this stage assumed a more controversial role in the struggle. Mugabe, ZAPU’s publicity secretary, gave an interview in which he derided PASU as a band of “political rejects and undesirables”. The suspicions that had once plagued Matimba now shifted to Mushonga. A letter to the editor of a Rhodesian paper wondered why the authorities allowed Mushonga back in the country after exiling him to London and suggested that he was operating on behalf of the white settler government.

Untimely end

Around 8:30pm on 2 December 1962, Mushonga, riding shotgun, died in a car crash. He was returning from an aborted attempt to meet Chikerema and Nyandoro, his former Youth League associates still languishing under government detention in Gokwe. He was accompanied by three PASU colleagues. The best known was Edson Sithole, one of his most loyal followers. Sithole became Rhodesia’s first black recipient of a doctorate in law not long before his own mysterious disappearance in 1975. Also present was Christine Monera, PASU’s enigmatic secretary for women’s affairs. The driver, Kufakunesu Svovera Mhizha, PASU’s chairman, had been detained with Mushonga following the emergency.

Sithole, a freelance journalist, was sufficiently unscathed to quickly compose a narration of the crash for the 4 December 1962 edition of the Daily News under the headline “Four Headlights Shone in Our Faces”.

The account describes the poor driving habits of other motorists, resulting in a situation where Mushonga’s car was faced with oncoming (stationary) traffic on both lanes of the highway. It does not explicitly make an accusation of foul play and is puzzlingly vague.

Decades later, Zacharias stated that the crash occurred on a stretch of straight road on a clear night. Contradicting Sithole’s article, he added that while his brother’s neck was broken, he didn’t have any scars on his face. While unstated, Zacharias’ intimation was that something untoward had happened between his brother and his fellow passengers.

Meanwhile, the survivors maintained that the crash was the result of intrigue by white opponents of the nationalist struggle. In a letter sent the day after Mushonga’s passing (digitised and released online by the British Library), Sithole stated that Mushonga “was silenced by settler manoeuvres aimed at eliminating African nationalists from the political scene of the country”. Parirenyatwa’s widow also went on the record, expressing her reservations about Mushonga’s death being an accident.

Mhizha was charged with culpable homicide and swiftly convicted within three weeks of Mushonga’s death. A remarkable press account relates that the presiding magistrate, RB Hunt, reached his verdict not on the basis of Mhizha’s driving, but because Mhizha’s defence (corroborated by Sithole and Monera) of a white-led, government sponsored assassination attempt was at odds with the verbal statement he supplied to a police officer at the scene of the crash.

Following Mushonga’s death, PASU collapsed, torn between Mushonga loyalists and a faction with close ties to Zimbabwe’s labour movement, represented by the party’s Vice-President, Phineas Sithole. An interview with the now late Phineas Sithole, produced virtually no recollections of his association with Mushonga, whom he had accompanied on the visit to the United Nations in October.

A contradictory man

When Mushonga passed away in December 1962, he was the leader of the foremost legally active nationalist party in Southern Rhodesia. He had some of the most significant international exposure of any Zimbabwean active in the liberation struggle, having cultivated an international network across Africa, Europe and North America, lobbying at the United Nations and participating in the historic All-African People’s Congress in Ghana. He had the backing of prominent black labour leaders in the colony and appeared poised to leverage the advantage of PASU’s legal status and ZAPU’s prohibition to some effect.

But his position was precarious.

He had been condemned by the leaders of the main nationalist wing and just days before his death had made a plea for reconciliation. His rhetoric indicated an intractable opposition to the white-minority regime, but the historical record suggests that his party may have been in cahoots with the settler government. Finally, there seemed to be significant tensions within the pan-African and labour wings of his own party, which resulted in PASU effectively collapsing upon his death.

Nearly 60 years later, it is unlikely that there will ever be a neat resolution of the claims made by Mushonga’s brother or the allegations of those travelling in the car with him. His political opponents in ZAPU, the Rhodesian government, and even a faction of his party all seemed unhappy with him. His brother cast suspicion on those who survived the crash and who seemed to be among his most loyal supporters.

Mushonga’s death, just months after the much-lamented passing of Parirenyatwa, a widely celebrated national hero, contributed to a consolidation of the paranoia that continues to influence views of independent-minded Zimbabwean politicians and their car crashes. The Rhodesian government’s seemingly vindictive decision to charge the drivers of both Mushonga and Parirenyatwa’s cars with culpable homicide, amidst allegations of its own responsibility, provided further fodder for public suspicions.

Zacharias Mushonga expressed regret that most histories of Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle did not take their “true forms”. Rather, “as far as present people are concerned, the struggle only started in 1975 and 1976 when people started flocking into Mozambique”. This lament was at the core of Ranger’s “patriotic history” critique. Dismantling this exclusionary discourse may help ensure that Zimbabwe finally gets its much yearned for ‘New dispensation’.