The aftermath of injustice

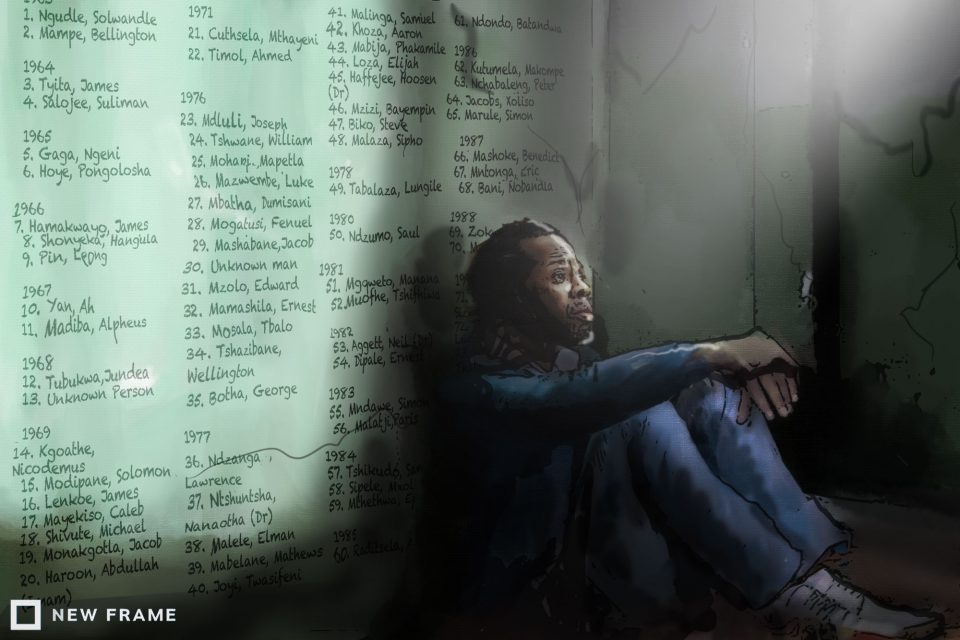

Only two inquests into detainee deaths under apartheid’s Security Branch have been reopened, but the values of the more than 70 activists who died at John Vorster Square live on.

Author:

24 January 2020

Neil Aggett was a South African who lived with a deep commitment to justice, and ultimately died in police custody in 1982. While not an official court case, the inquest into his death that reopened on Monday 20 January seeks to address the injustices that likely led to his death, which was officially recorded as a suicide.

With two of his detainers dead, it is unlikely that any form of punitive justice could ever be exacted. We will likely also never truly know what his last moments were like, perhaps in the ware-kamer (truth room) on the 10th floor of what is now the Johannesburg Central Police Station.

This week New Frame republished John Berger’s reflections on the photograph of Che Guevara’s body that was transmitted by his captors as proof of the rebel’s death in 1967. While their intention may have been to show that they had killed the man and in doing so the ideals for which he lived, his death, like that of Aggett’s, had the opposite effect.

Related article:

Berger writes:

“Guevara died surrounded by his enemies. What they did to him while he was alive was probably consistent with what they did to him after he was dead. In his extremity, he had nothing to support him but his own previous decisions. Thus the cycle was closed. It would be the vulgarest impertinence to claim any knowledge of his experience during that instant or that eternity. His lifeless body, as seen in the photograph, is the only report we have. But we are entitled to deduce the logic of what happens when the cycle closes. Truth flows in the reverse direction. His envisaged death is no more the measure of the necessity for changing the intolerable condition of the world. Aware now of his actual death, he finds in his life the measure of his justification, and the world-as-his-experience becomes tolerable to him.”

If, as Berger posits, the truth flows in the reverse direction, what can we deduce about what happened when Aggett and Guevara’s cycles closed?

Both men came from relatively privileged middle-class families in oppressive settler nations. Both were doctors and their commitment to justice was galvanised, at least in part, by their experiences of practising medicine in impoverished areas. Their ethical commitments were aligned in significant respects. Guevara’s famous quote, “If you tremble with indignation at every injustice, then you are a comrade of mine”, foreshadows Aggett’s sentiments expressed in a 1982 statement in which he wrote: “I felt that it was important that people should learn about their rights, learn to have self-respect, and therefore get rid of injustices themselves.” Both were acutely aware of class and its role in shaping society, and both were conscious that the rights and freedoms they enjoyed were denied to the majority of people around them.

Similar circumstances

The reopened inquest into Aggett’s death comes just three years after the reopened inquest into the death of activist Ahmed Timol, a teacher who died when he fell from the window of room 1026 of what was then the John Vorster Square police station in 1971. Timol’s death, like Aggett’s, was officially ruled a suicide. And like Aggett’s family, the Timols refused to accept the findings.

Related article:

The family of Matthews Mabelane, a 23-year-old student activist who died in detention in the late 1970s, attended the Timol inquest, hoping the same commitment to justice would be offered to them.

Writer Amanda Khoza, who was working for News24 at the time, spoke to Mabelane’s family. She was shown a chilling piece of evidence, a handwritten note that Matthews had stitched into the lining of his “dark green and bloodied Lee branded trousers”.

The note was addressed to his brother. It read: “Brother Lasch, inform Mum and my other brothers that the police are going to push me from the 10th floor and I am bidding you goodbye, forever.” He died on 16 February 1977. It was reported that he had jumped from the 10th floor of the building.

Of all the activists whose lives ended on the 10th floor of John Voster Square, only Aggett and Timol have had the dignity of an inquest into the circumstances of their deaths. Their rights have been defended after death by families who are able to afford the costly pursuit of justice. It is a privilege not extended to the more than 70 people who died while held in detention around the country. Justice should be a universal right, not a privilege.

Honouring legacies

We can never make up for the suffering and loss that came with the passing of these activists. We can, however, remember the values their lives and deaths came to symbolise. If Guevara and Aggett were alive today, it’s highly unlikely they would have been simply practising medicine, satisfied in their surgeries. Or that Timol or Mabelane would be content with their seats in a classroom, oblivious to the vastly unequal, unjust and intolerable conditions that prevail across this country, and this world.

Their lives and their deaths prove that, while you may imprison and even end another person’s life, you cannot extinguish the fact of their existence or the values by which they lived. In their absence, felt most sorely by those who loved them for who they were and not only for what they stood for, we can learn how to honour the legacy of their lives.

Related article:

Testifying during the inquiry this week, Aggett’s partner Liz Floyd said: “So long as the state continues to protect perpetrators at the expense of victims, the project of reconciliation will remain incomplete. We must never forget the ultimate sacrifices made by people like Neil for our freedom, and we should always remember that ‘freedom’ is not ‘free’.”

It’s what Aggett and Timol would have wanted. There must be justice for all those who suffered and died in detention. This is an urgent imperative.