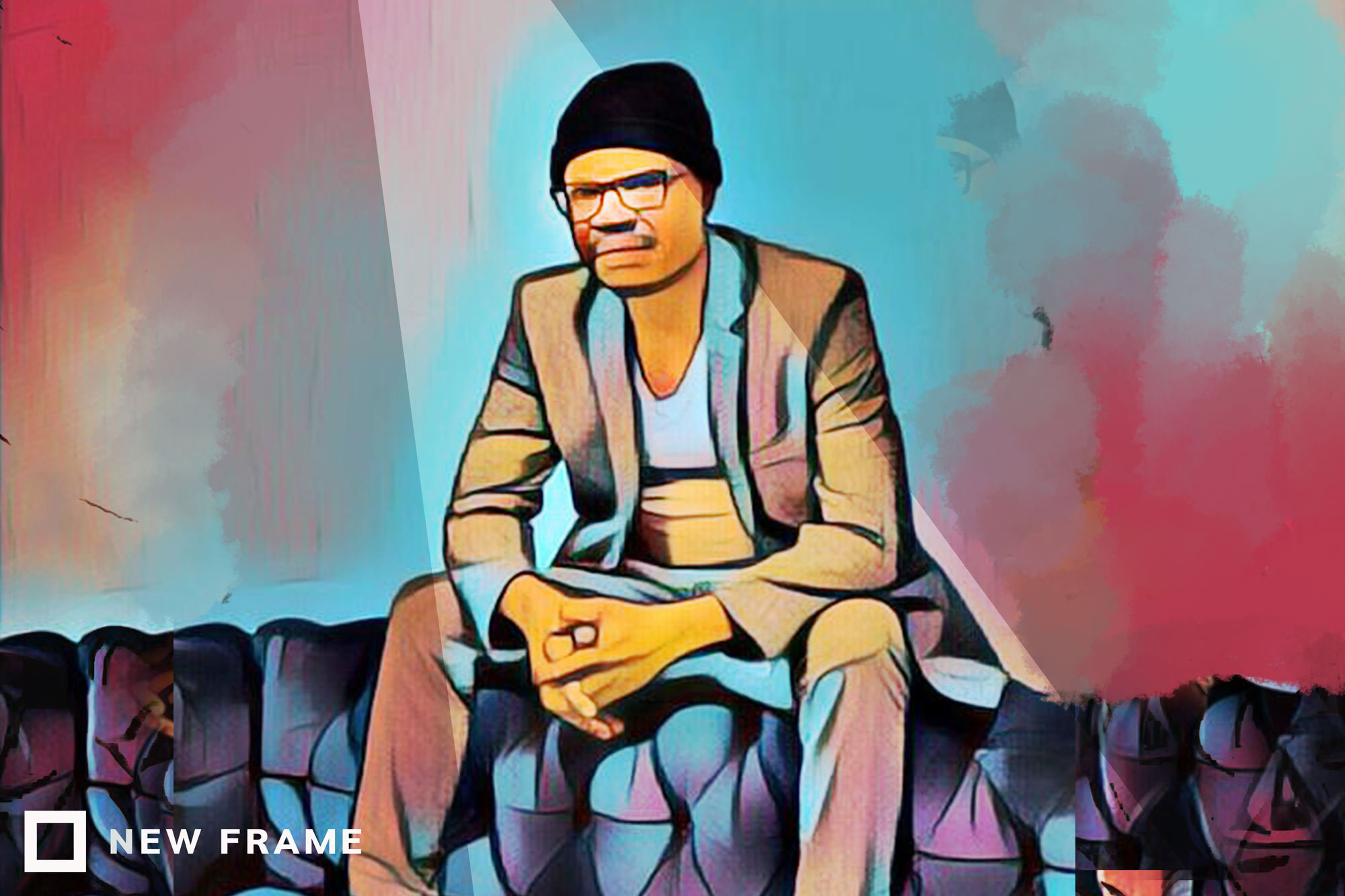

Thando Doni’s theatre without translation

The 2021 Standard Bank Young Artist for Theatre Award is a well-deserved recognition of the Cape Town theatremaker’s exceptional skill, talent and hard work.

Author:

8 November 2021

Thando Doni makes theatre look like magic. The theatremaker’s stages are spaces where love and the effect of alcohol have wine bottles appear unexpectedly, deftly pulled from beneath a table in a near endless loop. Where sacred are the bodies of four men as they lean over a basin to wash themselves. And where the birth of twins, with their writhing bodies and the thick white cord that binds them together, foreshadows the struggle from which they are never quite delivered.

Doni has a reverence for stories and uses them as a social vessel for whatever needs to be said. It is a skill that has seen him work with teenagers, former prisoners, theatre trainees, film students, large ensemble casts and puppeteers.

He has crossed the invisible divides that mark the craft of theatre in Cape Town and worked on stages as varied as the Artscape, the Baxter, the former matchbox factory that houses the Magnet Theatre, and even a church-turned-independent theatre in Observatory and the rent office that is now an arts space in Delft.

But it was the school halls, backyards and community centres in Khayelitsha that nurtured Doni long before he would be named the 2021 Standard Bank Young Artist for Theatre.

Related article:

His latest work is Ndiza Kuwe, which was performed to small audiences of no more than 15 at Theatre Arts in Observatory in August. It was Doni’s first offering since 2019 and featured Asanda Rilityana and Sisipho Mbopa as queer lovers Asithandile and Nontando. Seeing these exceptional performers together on stage was a rare joy, as they are often relegated to supporting or ensemble roles on Cape Town stages.

In the opening minutes, the audience was introduced to the things that Doni enjoys most – the use of isiXhosa, a strong and dynamic physicality, music as a character, and love. Asithandile and Nontando traded flirtatious barbs with a swing of a hip here, a coy laugh there and the exaggerated posturing that comes with new love.

Ndiza Kuwe reminded one of Mhla Salamana, in which Rilityana also played half of a union, but one that was falling apart owing to abuse, violence and infidelity. The production won Doni the award for best director at the Zabalaza Theatre Festival in 2011. One of the most memorable images was of a child lying on his mother’s back: both a responsibility and a burden that the woman had to carry in the face of her failing union. In Ndiza Kuwe, the lovers’ internal wounds threatened to tear them apart, and in their distress they similarly became child, burden and responsibility.

A physical style

In Doni’s work, the characters’ worlds are often expressed through physical gestures, creating strong visual impressions. This is not surprising. He, like Rilityana and Mbopa, is an alumnus of the Magnet Theatre’s full-time trainee programme, which was launched in 2008.

The Magnet, whose artistic directors are Mark Fleishman, Jennie Reznek and Mandla Mbothwe, is renowned for creating intensely physical theatre that foregrounds the language of the body. Both Rilityana and Doni were among the training programme’s first cohort of graduates, with Mbopa joining in 2012.

The programme has introduced many performers to this style of working and resulted in several productions, mostly in English but also some that were in isiXhosa, Afrikaans or multilingual. The style is not always easily translatable, though, and Mbopa recalls taking her aunt to watch her perform. “She would say the things that we do with our bodies are complicated, and because we only spoke English it was hard for her to relate,” Mbopa explains. “She would only enjoy the dance parts and the singing.”

Related article:

Thami Mbongo, an actor, activist and one of the founders of the Zabalaza festival, credits the training programmes created by institutions such as the Magnet, JazzArt Dance Theatre and Unima South Africa with introducing alternative ways of creating theatre outside of the homogenous theatrical sensibility that dominate traditional community theatre spaces.

He explains the importance of these styles finding “a way that audiences can really understand” given their potential to be alienating and inaccessible. Mbongo says the way in which Doni combines music, physical theatre and storytelling “makes it easy [to enjoy] even for someone who does not know different theatre forms”.

Doni told arts journalist Theresa Smith in 2012 that at the Magnet he was told to make theatre “that crawls under the skin. It must provoke something.” He delights in provocations that are deeply rooted in a social context. His fascination with movement predates his work in theatre.

Understanding the body

In high school, Doni was a cha-cha and ballroom dance instructor for a dance and drumming troupe called the Manyanani Entertainers. This might explain his sensitivity to the many ways in which bodies express themselves.

“I think he understands something about the body, the voice and the unconscious gesture,” says Kanya Viljoen, a young theatremaker who saw Doni’s 2019 production Isityhilelo. In the play, movement made clear the world of charismatic preachers and the dark underbelly of crime. “He knew the language. He knew the gesture of hitting on the Bible, or a cup in the hand that asks for money, or the tipping of a hat.”

Doni’s 2017 Phefumla! (To Breathe) extended the idea of body to include the set. The set designer connected corrugated iron sheets to a kinetic system that the cast, four former prisoners, could control. In quiet moments the set would breathe, reinforcing the idea that the environment in which the men lived threatened their breath, and therefore their lives.

In Ndiza Kuwe, the physicality was driven by the need for an intimate embrace. The two lovers moved between reaching towards each other, hugging, sleeping and holding. Each time they moved, their bodies were saying “I need you”, “I want you”, “Don’t leave me”, “Please save me”.

Related article:

To Mawande Sobethwa, creative group head at Publicis Machine advertising agency in Cape Town, Doni feels “like the second coming of Mandla Mbothwe”. Doni shares many stylistic and thematic elements with Mbothwe, one being their use of their mother tongue, which Sobethwa admires. “I’m a big fan of Mandla’s work and uThando Doni was a very refreshing take on what Mandla had been putting together and achieving in his tenure. It felt like the passing of the baton to a great extent,” says Sobethwa.

Mbothwe’s relationship with Doni is deep. Mentor and protégé, they are also co-conspirators, having most notably worked together on the adaptation of SEK Mqhayi’s Ityala Lamawele. However, there are marked differences in their work. “I normally work from the collective wound, which is the archives of the mass colonial crimes,” says Mbothwe. “He [Doni] always works from a place of love. Most of his productions are musically love-driven songs.”

Mhla Salamana did this beautifully, incorporating the four-piece a cappella group Muziek Sensation into the performance to act as a kind of chorus. Playing through speakers, the music in Ndiza Kuwe lacked this warmth.

Uncertain notes

Ndiza Kuwe revealed Doni’s strengths and weaknesses in equal measure. His usual weaving together of narrative, physical language and imagery did not coalesce. The lovers were introduced through a hyper-romanticised lens filled with poetic isiXhosa. The language was imaginative and expansive in the way that it encapsulated what Asithandile and Nontando were feeling. This world was disrupted by Nontando’s drinking, which was catalysed by the death of her daughter, and the two characters were pulled into separate worlds.

This world was again disrupted by the insertion of couple’s therapy, which felt like a set piece from a romantic comedy. The disjuncture between worlds was made more apparent when Asithandile and Nontando spoke to their therapist or told bedtime stories in English. The use of English felt forced, a deliberate attempt to draw in an audience that is otherwise divorced from the African language and the characters’ lives.

This was perhaps a marker of a theatremaker unsure, yet throughout Doni’s career he has deliberately told stories using isiXhosa not only to connect with his audience, but also as an assertion that these stories can be told without translation.

Related article:

Additionally, while Doni has explored a queer story before in the play Eutopia, in Ndiza Kuwe the lovers’ orientation seemmed incidental, which is refreshing but the couple remained displayed through the gendered division between the “masculine” and the “feminine”.

However, created under a level four lockdown and amid particularly violent taxi and bus protests in Cape Town, Ndiza Kuwe was special. At 35, Doni is an independent theatremaker who creates with whatever he has at his disposal. His versatility is seen by Nwabisa Plaatjie, coordinator and curator of the Baxter’s Masambe Theatre, as a talent but also a skill born out of necessity.

“Of course he can develop work from scratch, but that’s work of survival,” she says, pointing out that Doni creates his best work when he has the financial and creative freedom to collaborate with music directors, set designers and choreographers.

Related article:

Thembela Madliki, a theatremaker, director and part-time lecturer, says Doni is “an example of the amount of commitment and perseverance and just love for the craft that you have to have to continue doing the craft. I want to live in a time where we have his work in archives.”

It is true that Doni’s work is not easily accessible through archives. Despite this, he has already left an indelible mark on the Cape Town theatre scene. Ten years after its debut, Mhla Salamana remains one of his most memorable works. Ityala Lamawele is also a firm favourite. His adaptation of AC Jordan’s novel Ingqumbo Yeminyanya with the Magnet Theatre trainees earlier this year may signal a niche for Doni in the adaptation of classic isiXhosa texts. Doni’s work deserves recognition. Ndiza Kuwe was a reminder that he is best when he is giving breath to stories and that Cape Town theatre, and that of South Africa, is at its best when he is given room to do so.