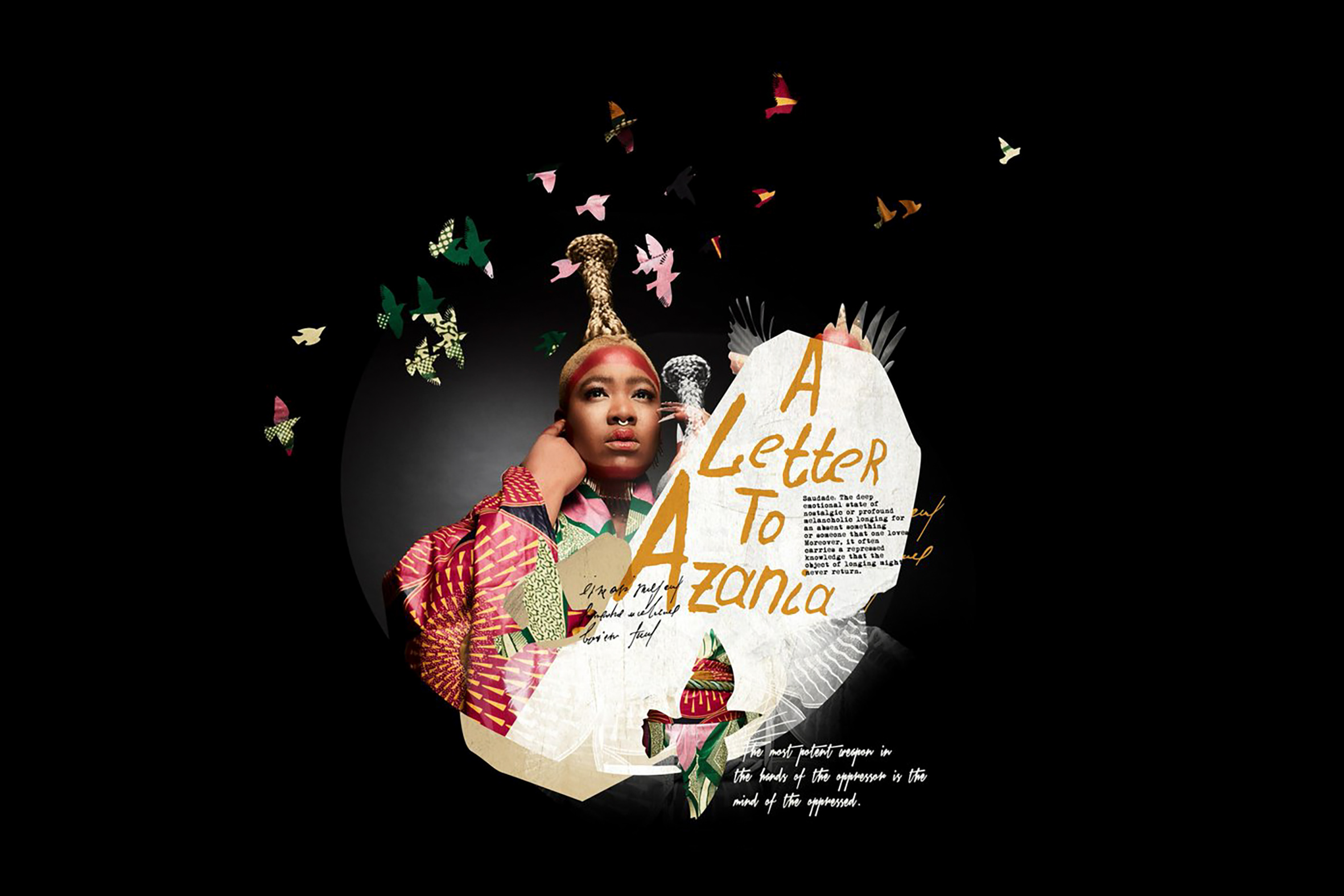

Thandiswa Mazwai pens a letter of love to Azania

Admittedly pessimistic and disillusioned by the many ills in South African society, the influential singer has nevertheless resolved to fight for the country she wants.

Author:

23 March 2022

It’s 2013 and Thandiswa Mazwai is being interviewed by a room full of journalists clamouring for her attention in the run-up to her performance at the Cape Town International Jazz Festival. One of them asks the singer what she thinks has changed since the advent of democracy in South Africa.

Pausing for a second to mull it over, Mazwai answers: “Not much.” She lets out a short, wry laugh. “Not much has changed. But the big change is in my mind. The realisation that I am a free person. That’s the main change … Black people are starting to recognise that the world is theirs as well. You know, that it’s not just for white people. It’s also for us.”

The interview was filmed as part of a short film for Rolling Stone magazine by Aryan Kaganof. The end sees Mazwai tapping an invisible watch on her forearm, indicating to her crew that interviews are now over, the audience is waiting and the show needs to start. That night, she delivers a performance that is, in one word, transportive.

Related article:

Now, with close to three decades in the music industry under her belt, Mazwai, 46, is undoubtedly an icon of South African music. Her first album, 2004’s genre-fusing Zabalaza, reached double platinum status and won numerous awards. This was followed by 2009’s Ibokwe, while her third album, Belede, was released in 2016 and reached gold status within a few weeks.

While her albums have garnered much critical acclaim and commercial success, it is her live performances that make her incomparable. A consummate performer, she is always strikingly dressed and engages her audiences with a charming mix of playfulness and reverence. And with her latest show, the simply yet poignantly titled A Letter to Azania, Mazwai is yet again delivering the goods.

Billed as “a sonic exploration of the utopian idea of Azania”, the show gives voice to “the melancholy that comes with a dream deferred”, according to its press release. Moreover, it centres around what Mazwai feels South Africa needs desperately: “A love for the people, a love for country and a love for justice.”

Sense of loss

By her own admission, Mazwai today is “disillusioned” with the sorely lacking version of democracy into which South Africa – or Azania, rather – has morphed. King Tha, as she prefers to be called, lets out a sigh as she says the idea for the show was born from “an overwhelming sense of loss that comes with freedom sometimes”.

She grew up in a Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) family. “Both my parents were PAC, so freedom was encapsulated in this idea of Azania. Not only as a name change for South Africa, but as this utopian place where there would be no violence, where there would be autonomy of mind, body and spirit.

Related article:

“But for a Black, queer woman such as myself, the distance between where I am and real freedom is still very far. Where, for instance, I don’t fear violence from other human beings. There was the assumption that by following principles such as ubuntu, we would evolve enough to arrive at a utopia. But what continues to happen, as I see it in South Africa, is that we’re going deeper into a dystopia, into a kind of madness.”

Fighting against this descent into madness has seen the singer, who was born in the Eastern Cape and raised in Soweto, making activism a core part of her identity as a musician and public figure. She does it on many fronts, whether it is taking to Twitter to plead for state security forces to treat South Africans with dignity during the Covid-induced lockdown, or throwing birthday parties centred on women and queer folk.

Still, as she says in the short film, “I’m afraid to call myself an activist. Because I don’t know if there’s a certain level of activism that you must do to consider yourself an activist. You know, I think I just keep it simple and that’s how it works.”

Lockdown letdowns

As with virtually everyone in the arts sector, lockdown restrictions have had a significant impact on Mazwai. To her more than 300 000 Twitter followers, she wrote: “Did you know that some European government is paying South African jazz musicians a Covid grant every month?” This was followed by: “Imagine another government doing for us what home should do instead of looting.”

“I think we’ve always known that we don’t really have any support within the government and that the department of arts doesn’t really understand the intricacies of our world,” she says. “And because of that lack of understanding, they’re not able to see or foresee what we need.

“For instance, it was quite late, like six months ago, that Madala Kunene sent me this message. He was like, ‘Yo, did you apply for this money from the Swiss government? They’ve been taking care of artists the whole time. Maybe you can get some.’ I thought okay, cool. Let me just apply. And I got that money. And it really helped me and my band.”

Related article:

Being assisted in this way, Mazwai concedes that she missed the stage more than anything. “I just missed singing. So I had to find different ways of dealing with my emotions, because a lot of the time I would exorcise a lot of my issues on stage. The stage was that space for me where I could configure myself and re-energise myself. That’s really the thing that I missed the most.”

She adds that the pandemic and lack of government support for the arts sector have put artists, as with all South Africans, in a position where they “just need to self-sustain. And to think of ideas of how you will survive, because the government is anti the people in South Africa. They prove it time and again.

“You know, in all this time, they’re still talking about pit toilets for school kids. We are 30 years into our freedom. We are so far into our freedom, yet there are so many things that just make no sense for a ‘government of the people’.”

The persisting plague

Although the pandemic is seemingly on the wane and the country is crawling slowly back to normalcy, South Africa’s “second pandemic” – as President Cyril Ramaphosa referred to the scourge of gender-based violence – continues to plague women, children and gender minorities nationally.

Letting out another frustrated sigh, Mazwai says that many social ills have become normalised “under what bell hooks calls ‘the white supremacist patriarchy’”. This, she says, includes the abuse of women, seeing them as lesser beings and how South Africans in general tend to ignore the “crazy levels of violence” against women as well as queer and Black people.

“I don’t think that society has reached a place where we are fully aware of how much of our humanity has eroded that we are able to live with the kind of violence that we live with, the kind of inhumanity that we live with. The distance between humanity and love and the way that we live now is so vast,” says Mazwai.

“I do think that there are a lot of feminist activists who are doing a lot of great work to try and push government to do a lot more towards the defence of women, children, queer people – the defence of those who are defenceless. And I think that we need to support the work of these people, because they’re the ones that understand the most about what measures need to be taken by the government, and by society in general, in order to change our world.”

Speaking about ways to address this, she says men need to speak more to each other about dismantling sexism and patriarchy. “And also gaining a much greater understanding that sexism and patriarchy are chained to men as much as they are to women. Because men are expected to follow some of these gender roles that they themselves cannot keep up with.”

Given the immense gap between the Azania she was raised to dream of and the country she is living in, does she hold out any hope for South Africa’s future? Without a moment’s hesitation, Mazwai answers: “We must remain hopeful. We still have to believe that we can do better, that we can create better.

“So, as much as I think I have definitely become a pessimist, I think that we have to fight to remain optimistic. We have to fight for beauty to remain in the world, for love to have space to grow. I still believe in that South Africa. I still believe in that world. We all still have to believe in the possibility that one day we can all prosper as a humanity.

“That’s what A Letter to Azania is about. It’s about trying to create that crack in the wall. It’s about trying to remind us of what we can be, what we can create when we’re together – the energy of love and joyfulness that we can create. And then try and take that out into our own worlds, and into our homes.”

A Letter to Azania will be performed at the Durban Playhouse on 26 March at 7pm.