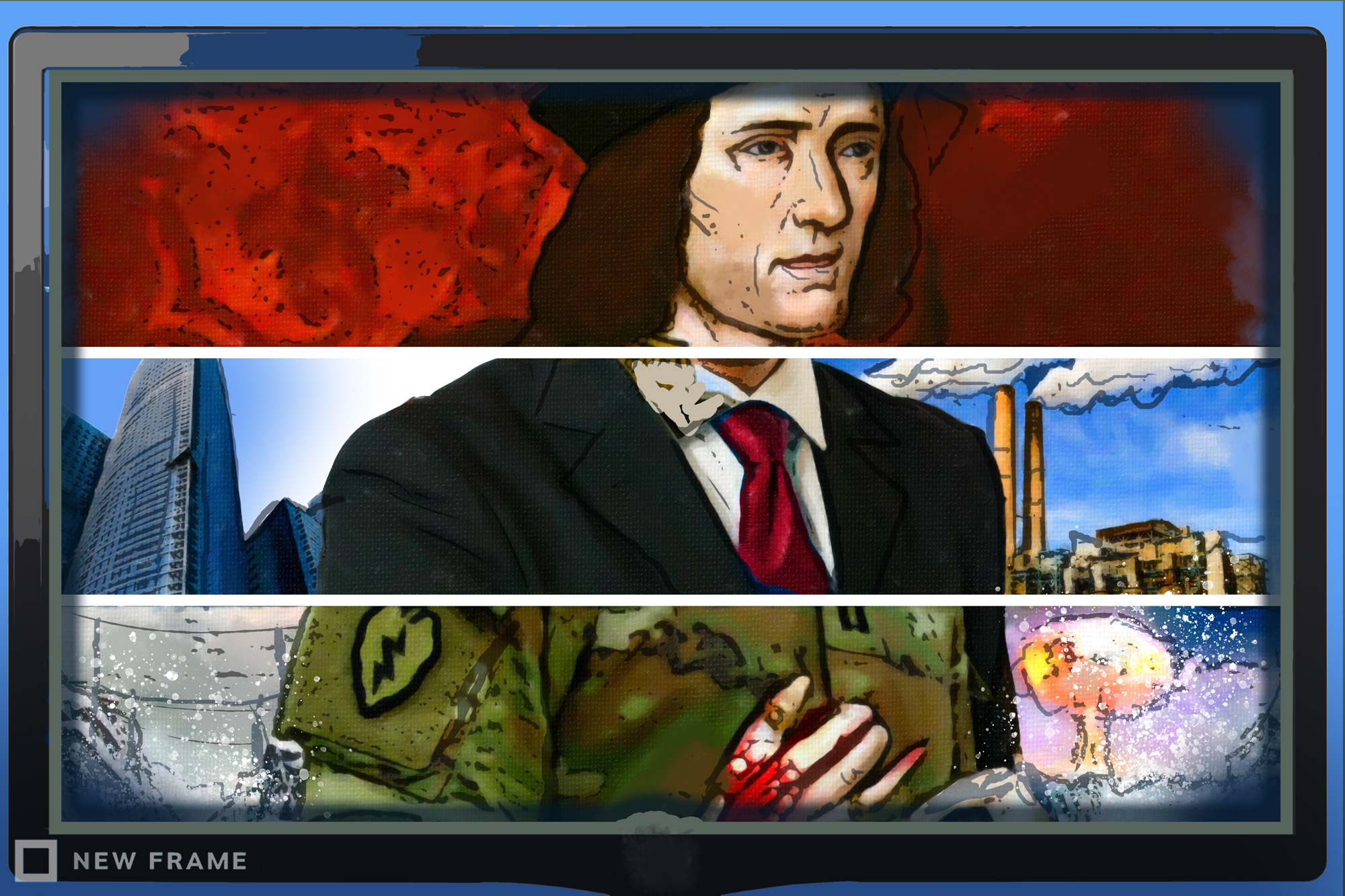

Text Messages | Whose history?

History is in a dynamic relationship with the present, never more so than now. By all accounts, King Richard III was a bloodthirsty fiend – until the truth was unearthed.

Author:

25 June 2020

Whatever the eventual outcome of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests, the world is witnessing history in the making – and the unmaking. The dominant historical narrative that the BLM protesters oppose and wish to correct is a record and interpretation of the past created by the winners for the winners.

There has perhaps never been a moment so filled with the possibility of fundamentally changing the way some of the past is reflected as now. A full, properly rounded perspective on the events of the past is supposedly the ambit and vocation of the historian. One of the finest historians ever, author of the monumental History of Soviet Russia, EH Carr, noted that the discipline is “a continuous process of interaction between the historian and his facts, an unending dialogue between the present and the past”.

Carr maintained that the dual function of history is to understand the society of the past and to increase mastery over the society of the present. And he pointed to the fundamental questions underlying the pursuit: “Good historians, I suspect, whether they think about it or not, have the future in their bones. Besides the question ‘Why?’ the historian asks the question ‘Whither?’”

Related article:

So, whether the global BLM movement results in deep and systemic change or in the establishment resisting and reimposing the status quo, the world will have benefited from an enlarged answer to the “Why?” of the past and a more nuanced understanding of where we are – or, ideally, should be – heading. Still, that is to overestimate the capacity of the human animal to learn. As the Spanish-born philosopher George Santayana put it in The Life of Reason (1905), “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Given that much of that past is deliberately wrapped in propagandistic retelling, there is a lot of unwrapping to do. Fake news did not begin with Donald Trump’s dishonest labelling of news unfavourable to him as a counterfeit product. Arguably among the most blatant rewritings of personal history for political gain is the case of Richard III, who ruled England for two short years, 1483 to 1485.

The stories we tell

Conventional and received knowledge about Richard III is that he was a hunchback with a withered arm, a wizened and wicked manipulator, the murderer of the two young princes who had bloodline claims to the throne, and a general all-round baddy. For this portrait we have to thank, of all people, first the noble and saintly humanist Sir Thomas More and second the peerless William Shakespeare.

In 1513, More published History of King Richard the Third, a masterpiece in subtle character assassination. Its deftness would not be appreciated in our age of shout-out tweets but its efficacy is undeniable because it validated the Tudor monarchy at the time and ensured that for more than 500 years Richard III has routinely been regarded as a bloodthirsty villain.

Then, of course, there is Shakespeare’s great play The Tragedy of King Richard III, performed first in 1592 or the following year. Using More, Shakespeare extends the literary and historical conceit of Richard as the personification of irredeemable evil. It starts from the play’s first soliloquy, given by Richard, which famously begins “Now is the winter of our discontent/ Made glorious summer by this son of York” before moving on to: “I am determined to prove a villain/ And hate the idle pleasures of these days.”

Related article:

Between those, Richard describes himself as “Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time/ Into the breathing world scarce half made up”. And yet, when his remains were found beneath a car park in Leicester in 2013, the postmortem showed no withered arm and at most scoliosis that meant one shoulder might have sat higher than the other.

The Richard of the “historical record” and of countless productions of Shakespeare’s play in which the actor playing him has been encumbered by all manner of hunchbacks, shrivelled arms and dragging gaits, did not exist. It was the historian Philippa Langley whose research and writing enabled both the finding of the king’s body and a short, sharp rewrite of the history books as to his physical state and his alleged bloodlust.

Finding Richard

In Langley’s Finding Richard III: The Official Account of Research by the Retrieval and Reburial Project and The King’s Grave: The Search for Richard III, the first co-authored with multiple contributors, the second with Michael K Jones, a different picture of Richard emerges. Elsewhere, Langley has emphasised that Richard introduced laws that favoured the peasants over their masters and that contemporary accounts show a picture of an efficient administrator keen to listen to the people.

But all of that stands in counterpoint to more than five centuries of anti-Richard rhetoric, none more powerful than the picture that Shakespeare painted. Fiction can sometimes be stranger than fact: so much for history and its multiple, mutable versions of the past, of “truth” and truth. Maybe James Joyce had it more correct than most when he ascribed the following to Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses: “History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.”