Text Messages | Grubby reality of reconciliation

The holiday dedicated to Mandela’s ideal of a South African nation marching together into the future has lost its meaning in the immoral politics that his successors have embraced.

Author:

16 December 2020

The Day of Reconciliation, 16 December, was not always so named. Nor was its intent to reconcile. For decades, it served as a triumphal emphasis of a minority’s subjugation of a majority, cloaked as a commemoration of a victory in battle.

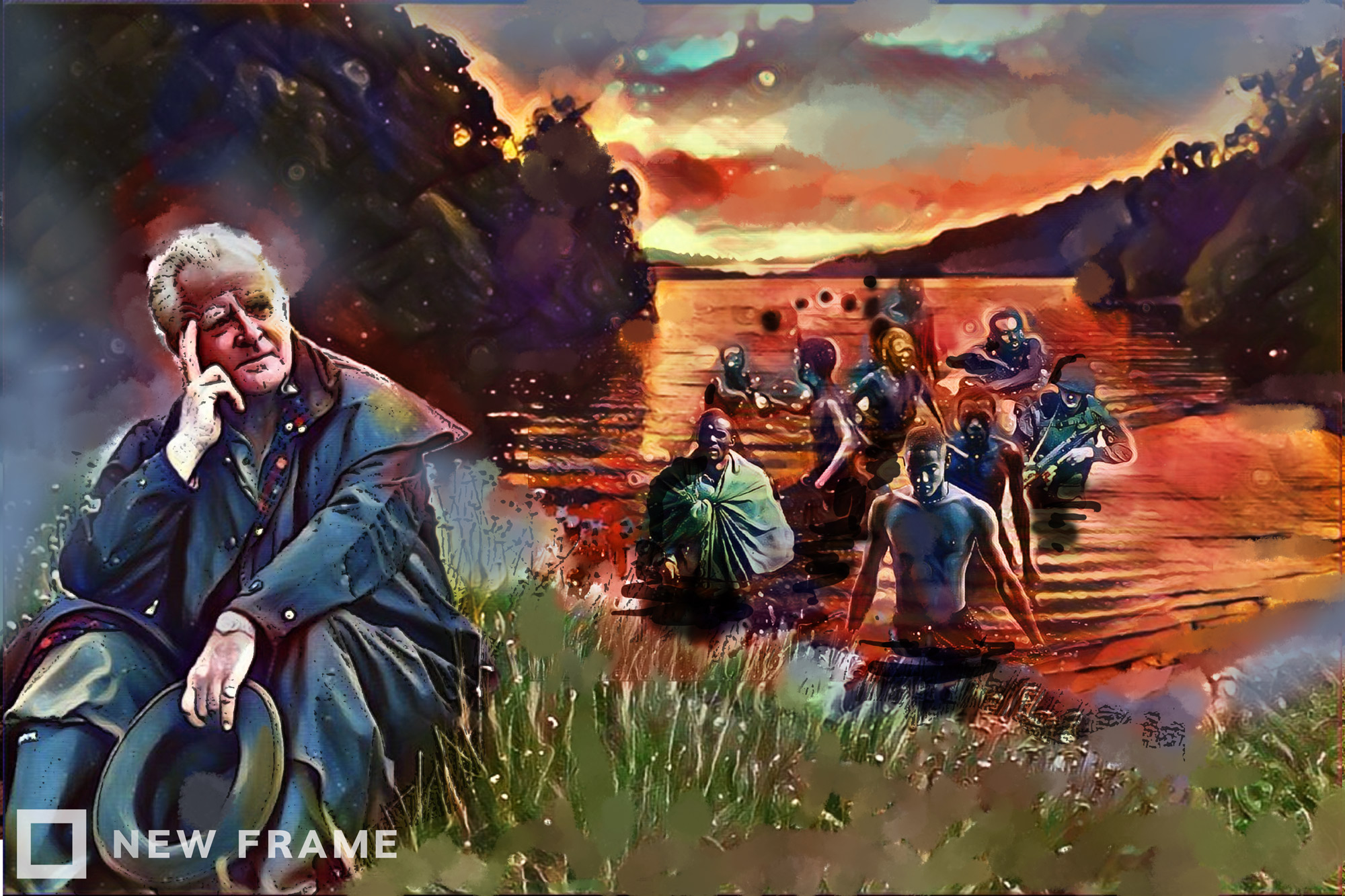

That encounter took place near the Ncome River in KwaZulu-Natal on 16 December 1838. Led by Andries Pretorius, a commando of 470 Voortrekkers had circled their covered wagons, awaiting attack from Zulu regiments estimated to number between 10 000 and 20 000, under the generalship of Dambuza and Ndlela kaSompisi. The vast difference in forces was compensated for by the commando having guns, which wrought devastation: Zulu deaths were tallied at around 3 000, whereas inside the laager there were only three wounded and none killed. Such was the bloodletting that the Ncome ran red, which gave the name Blood River to the battle.

The Voortrekkers and their descendants never forgot the importance of the day, nor their debt to the divine, to which they ascribed and dedicated the victory. Various names were used, from Day of the Covenant to Day of the Vow, the latter first celebrated on 16 December 1864. The most offensive name, and long in popular employ, was Dingane’s Day – a reference to the Zulu monarch at the time of Blood River.

Related article:

Post-apartheid South Africa, with its initial remit of reconciliation, first celebrated the Day of Reconciliation in 1995. It might seem odd that a day with such resonances for Afrikaner history should simply have received a makeover, but the new name was not just cosmetic because 16 December had deep significance for the liberation struggle as well. It was on that day in 1961 that Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC, was founded.

That was a synchronicity which then President Nelson Mandela and the fledgling Truth and Reconciliation Commission seized with relish to advance their mission of creating better relations between South Africans and of showing that compatibility between them could become real. As history shows, reconciliation gave way to pernicious race politics under Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki, and then to lies and compromise under Jacob Zuma. Rarely has the waiving of principles for the settlement of personal gain been more visible than in the dozen years that Zuma was president. South Africa’s age of compromise continues under President Cyril Ramaphosa, a man of neoliberal instincts at the head of a former revolutionary movement that expediently retains tenuous links to its origins and founding principles.

A dream unrealised

Reconciliation is possibly as defunct as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, respectively a noble idea and a mechanism, both brought low by grubby reality. It is an outcome that would have saddened Mandela.

In his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, he wrote: “From the moment the results were in and it was apparent that the ANC was to form the government, I saw my mission as one of preaching reconciliation … At every opportunity, I said all South Africans must now unite and join hands and say we are one country, one nation, one people, marching together into the future.”

Related article:

Mandela had the moral authority to make such a call plausible and inviting. Other leaders have been ruinously self-compromised – Mbeki by his reckless and repeated playing of the race card and his intransigence on HIV and Aids treatments, Zuma by his solipsism and utter lack of morality, and Ramaphosa by the slaughter of miners at Marikana and his warm embrace of neoliberalism.

Mandela often remarked how it was the great novelist Chinua Achebe “in whose company the prison walls fell down”. As this piece was being drafted, news came of the death of John le Carré, the English writer. Given Le Carré’s deep moral sense, it is not idle to speculate that Mandela would have liked his work too, for it is filled with kindred spirits committed to the anguish, despair and probable failure that haunt all such endeavours to uphold one’s moral being, to do no harm and to live – and, if necessary, to die – for one’s convictions.

The pain of Le Carré’s conflicted characters, spies struggling against the deceitful web of their world, and very often the selfsame web spun by their very own masters, is the mortification of men and women who know there are no easy answers. And, ultimately, who know that fidelity to their principles and their innermost beings is what matters most.

‘It was too late’

Resisting moral compromise, there is nonetheless reconciliation to reality, as well as accommodating the inevitable. The final sentence of Agent Running in the Field (2019), what will now be the last book published in Le Carré’s lifetime, is almost a summation of his concerns: “I had wanted to tell him I was a decent man, but it was too late.”

That pithiness of mind and style – as with Virginia Woolf and JM Coetzee, there are no superfluous words in Le Carré – is another hallmark, and among the reasons that prompted Philip Roth to describe A Perfect Spy (1986) as the “best English novel since the war”.

Longtime colleague Gwen Ansell put it best, on the morning we exchanged messages about Le Carré’s passing. “For me one of the writers who enacted the truth that there is no barrier of quality – or indeed kind – between literature and ‘genre’ literature,” she texted.

Possibly the greatest accolade that could be paid to Le Carré comes, again, from Ansell: “The Graham Greene of our era – but without the Catholicism?”

The end of Our Game (1995) bears witness to that rich judgement:

“But the chanting was by now too loud, and he couldn’t hear me even if he wanted to. For a moment I stood alone, converted to nothing, believing in nothing. I had no world to go back to and nobody left to run except myself. A Kalashnikov lay beside me. Slinging it across my shoulder, I hastened after him down the slope.”