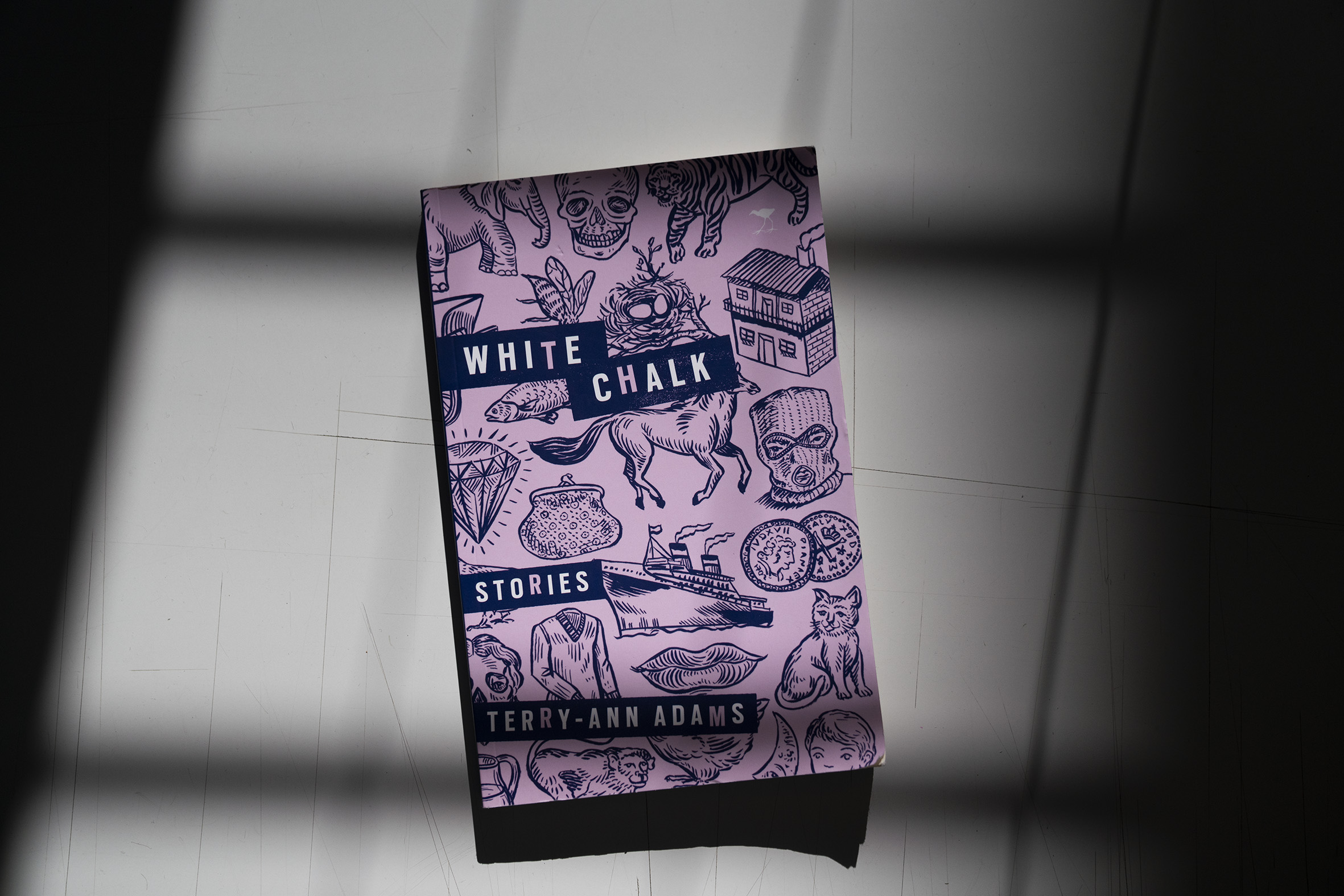

Terry-Ann Adams draws finely with ‘White Chalk’

In their second book, a collection of short stories, the author takes from their own life and losses and aspires to create a new world that is better for all its diverse inhabitants.

Author:

21 June 2022

“If it wasn’t for therapy, we wouldn’t have this collection,” says Terry-Ann Adams of White Chalk, their newly published short story collection. “Because I want everything I do to be authentic, I have to draw from the well that is within, unfortunately.”

Fortunately and unfortunately. White Chalk begins and ends in the face of death, and what lies between is punctured with sorrow and trauma, much of which is the author’s. Drawing from this, Adams takes to their blackboard and sketches a colourful picture of joy, innocence and vibrancy, bringing what was written across the pavement in times of youthful play for all of us to see.

Adams’ first novel, Those Who Live in Cages, took a microscope to their community of Eldorado Park, confronting “the socioeconomic difficulties and violence that exist in – but do not characterise – the area”. In White Chalk they zoom out this lens, while keeping the same attention to detail that characterised their debut.

“I think with Those Who Live in Cages the community was so well defined,” the author says. By contrast, White Chalk remains rooted in their community but this time foregrounds its many faces. “With White Chalk, we have different communities. We’ve got the disability community, we’ve got women, we’ve got gender diverse people, we’ve got queer people, we’ve got so many different communities represented within the book. And it’s about doing all of these communities justice.”

That idea, tracing back to their brief stint as a journalist, is incredibly important to Adams. They’ve come to learn that “when you write about people, you need to write about them in a way that reflects them and who they are. You’re not writing for them, you’re not a voice for the voiceless. You’re more like an amplifier or a megaphone for people who have their [own] voices.”

In this way White Chalk is more a kind of anthology of voices, more often than not using the first person to channel this. The story Matric Dance brings protagonist Robyn to a point of reflection. “I am not a girl … I am not a boy either … I am neither, and sometimes I am either, and sometimes I am both. I don’t know how to explain it to my mother; hell, I can barely explain it to myself.” The effect is at times more devastating: “I tell her that living is exhausting.”

A sense of recognition

With so many overlapping identities and communities, it is testament to their literary and observational skill that Adams’ collection speaks directly to the senses, in a way that is unmistakably South African. They evoke the all-too-familiar tenderness and “sanctuary” of a Black grandmother’s home, “the epicenter (sic), the watchtower, fortress of solitude and the HQ of our family”.

“The smell of Jungle Oats wakes us up in the morning,” Adams writes in the story Ma’s House. In the afternoon comes “an impressive Sunday lunch with all seven colours present and accounted for” and in the evening “the house is filled with the smell of braai meat”. In the time in between, “Ma’s house smells like Handy Andy, preserved peaches and homemade bread”. It’s a precision that can only come from a lifetime of memories, yet at the same time it paints a scene straight out of every Black South African home come the festive season.

One wonders then, with such an insistence on the personal voice of character and the local texture of setting, why Adams chooses to abandon the novel and slip into the short story form. “Novels want completion,” they say. “What I like about short stories is that it’s a play between reader and writer. We work together to come up with the ending of a story.”

Related article:

Indeed, part of its thrill is that White Chalk leaves much to the imagination. Asked what pulls a collection of 18 short stories together, each their own universe, Adams is clear. “I think if there’s one thing that’s a golden thread throughout all of the stories it’s that there’s a mental health issue.”

Mental illness – the stigmatising of it, its apparent ubiquity and many remedies – is front and centre, but crucially it is never viewed in isolation. In fulfilling their mission to “open up society to itself” Adams resists the politicisation of identity and uncovers the hurt – the person – that lies underneath.

They connect mental illness to religion and its many ugly heads, recounting “the year Brandon went to a Christian school and got bullied by children who were supposed to be Saints of the Lord”. Andrea, in Homecoming, walks away from her coloured home where “blackness to [her father] was imperfection … He aspired to whiteness and wanted us to do the same.” She is damaged by the pain this upbringing has caused her. “Home is supposed to be where you find yourself. In some strange way, I did find myself. I found an anxious, depressed wreck underneath all the rejection and torment.”

Adams connects mental illness to grief, too, the collection’s other through-line. Writing through their own loss, the author delivers a book of short stories that fulfils an incredibly difficult objective: to find meaning in devastation. Rooted in the real, it is the kind of meaning that holds up to scrutiny, which readers can cling to and take far beyond the book’s final word.

Resisting erasure

Adams’ attempt at solace finds its way into the collection’s title. “As easily as [white chalk] can be a weapon is as easily as it can be erased. It’s almost representative of what our lives are. As much as we can make a mark in a very short time is as much as we can die, and be erased. So I like the imagery of something that is so powerful yet so fleeting, yet so fragile,” they say.

Yet Adams extends beyond this, rejecting the image of grief we’re accustomed to seeing and speaking instead of the many different things we grieve. Of their story Beaches they note: “[The speaker’s] not just grieving the death of her mom. In some way, she’s always been grieving a part of herself that she’s lost to the fact that she’s had albinism. The same thing with Sunday Morning – it’s not just that she grieves her sister, but she grieves the life she would have had if she didn’t have albinism.”

It’s something Adams has recently discovered. “I’ve been grieving that part of myself that I couldn’t be because I have albinism,” they say, “and I’m only now becoming myself and living without shame and accepting disability. So I wanted to show not just the grief of death, but the grief of the self.”

Brought together, this intersection of ideas and identities reveals White Chalk’s most enduring quality: that at its best, it is profoundly aspirational. Bit by bit, its 18 short stories piece together a new and better world. It is a world in which a person doesn’t have to “come out” because sexuality is understood to be fluid and individual; where a baby isn’t forced to grow up in a room painted either pink or blue; where therapy is understood as essential, not damning. Adams doesn’t do this by naively turning away from society’s ills. Instead, they confront them head-on, both personally and creatively. When we’re lucky, they do both at the same time.