Switchover to new HIV drug is not all smooth sailing

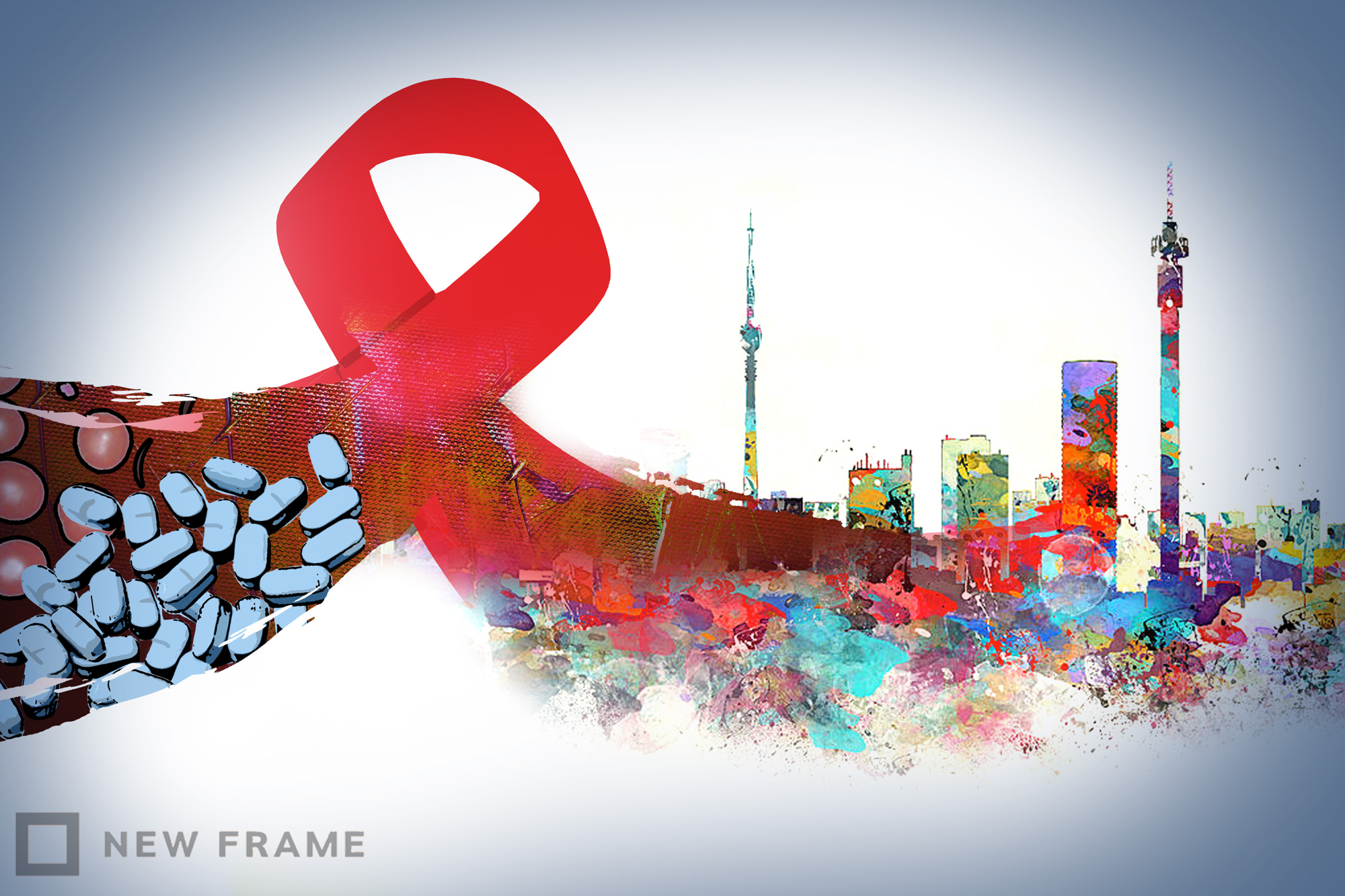

Three years after the health department started providing antiretroviral drug dolutegravir, close to 3.2 million people are taking it. But switching all these people has been a massive undertaking.

Author:

7 June 2022

The introduction of the antiretroviral drug dolutegravir arguably represents the biggest advance in HIV treatment in the past decade. Dolutegravir is highly effective at suppressing HIV in the body, it has fewer side effects than the drugs it is replacing and HIV struggles to become resistant to it. It is also cheap.

In 2018, the World Health Organization recommended that dolutegravir form part of the three-drug combinations that make up first and second-line HIV treatment. Not long after, dolutegravir was included in South Africa’s three-yearly antiretroviral tender.

According to Foster Mohale, the spokesperson for the Department of Health, a dolutegravir-based regimen – consisting of the drugs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, lamivudine and dolutegravir (TLD) – was adopted by the department in December 2019 as the preferred first-line regimen for people starting HIV treatment. The key change from previous regimens was the replacement of the drug efavirenz with dolutegravir.

Related article:

The rollout of TLD was conducted in two stages. Men, adolescent boys, women on reliable contraception and older women were initially prioritised. The caution was because of safety concerns in pregnant women raised by the Tsepamo study conducted in Botswana. Findings from the study suggested that there was a higher prevalence of neural-tube defects (a type of birth defect) associated with dolutegravir exposure at conception than with other types of antiretroviral exposure.

The second phase of the rollout began in 2021, according to Mohale, when results from a Brazilian cohort study and two large clinical trials in Africa showed the risk of neural-tube defects associated with dolutegravir is significantly lower than had been feared. Women with the potential to have children, adolescent girls and women who are breastfeeding were now included in the rollout.

Mohale says that by the end of March 2022, close to 3.2 million (3 198 757) people with HIV were on the dolutegravir-based regimen. He adds that facilities in all 52 of South Africa’s districts are currently initiating and transitioning patients to the dolutegravir-based regimen.

According to the latest estimates from Thembisa, the leading mathematical model of HIV in South Africa, around 7.9 million people had HIV in South Africa in 2021, of which 5.5 million were taking antiretroviral therapy.

Switching too slowly?

Francois Venter, a professor and the director of Ezintsha at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), says the inclusion of dolutegravir is a huge step forward for South Africa’s HIV programme. “It is so potent that some patients on second and even third line are able to move on to first line, which is better tolerated with far fewer tablets,” he says.

While people new to HIV treatment are being started on dolutegravir, there appear to have been some delays in switching people from efavirenz-based regimens to dolutegravir-based regimens.

Related article:

“A lot of people seem to have been left on efavirenz, for reasons that are not apparent – probably a compilation of lockdown, lack of investment in clinician and patient education, and apathy,” says Venter.

Based on findings from several recent studies, the Southern African HIV Clinicians Society (Sachs) updated its recommendations in May regarding the criteria for switching patients to dolutegravir. Previously a suppressed viral load was required before patients on efavirenz-based regimens could be switched to dolutegravir, which Sachs says has held back the transition. The new Sachs recommendations also open the door to more switching from old second-line regimens to dolutegravir-based regimens.

A district perspective

Josephine Otchere-Darko, a doctor and programme head of the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute’s HIV/tuberculosis care and treatment programme in Ekurhuleni, says that initially there were mixed emotions and a slow uptake owing to fears around the use of TLD, particularly in pregnancy. Yet uptake started to increase a little after the studies that essentially “nullified the neural-tube defect issue”.

In Ekurhuleni there was a slight upward trajectory of uptake of TLD just before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. During the early stages of the pandemic, she says the district saw a huge spike in the uptake of TLD. She explains that this was likely owing to patients not coming into clinics or not staying at the clinics for long, as well as a shortage of the efavirenz-based regimen. Clinicians then had to start using the TLD stock that was available.

Related article:

Otchere-Darko says uptake in Ekurhuleni has since plateaued. “Clinicians have chosen to either do it or not, they’re comfortable in their space, whether they are switching patients or initiating patients [to dolutegravir].”

She adds that initiating new people on dolutegravir in the district is going well. But switching people to the dolutegravir-based regimen has been challenging, as it takes a lot for clinicians to switch patients who are already on another regimen. “But we as support partners are doing that supervision part … We audit files and pick up patients that are eligible for switching and we are making sure that we’re switching them because that is one of our mandates as well,” she says.

Concerns over weight gain

According to Venter, weight gain as a potential side effect of using dolutegravir remains a big concern, but the actual weight gain might not be because of the drug itself.

“We do not think it [weight gain] is due to dolutegravir, but due to SA’s very obesogenic environment, and some data that suggests that HIV, especially HIV that is allowed to advance far along the immune deficiency spectrum before starting ARVs, primes people for obesity,” he says.

“The old ARVs were toxic and tempered this weight gain, and DTG is much better tolerated – but paradoxically that means more weight gain,” he says. He adds that broader strategies are needed to address this, as simply switching ARVs won’t help.

How is weight gain managed in the public sector?

Mohale says that at HIV treatment initiation, people are supposed to be informed of possible weight gain as a side effect and should be advised on diet. “As part of training, the clinicians have been informed about the possibility of weight gain as the side effect for clients on dolutegravir-based drug regimen so that they can report accordingly,” he says.

“Nevertheless, since rollout of TLD in the country, no weight gain reports have been reported,” he says. “Clinicians are advised to report any side effects and adverse events.”

Otchere-Darko says that in her experience, the component of preventing weight gain in patients starting on or switching to TLD is sadly not there from the beginning owing to a lack of clinician sensitisation to the seriousness of the issue. Ideally, she says, because weight gain is a known possible side effect, patients should be informed about this as well as counselled on lifestyle modification, provided a comprehensive plan to mitigate weight gain and be referred to a dietician.

Related article:

“However, that’s the ideal. We don’t have the capacity, so we don’t do that,” she says.

Usually, she explains, such support is started only after a patient has gained weight. The patient will be monitored in terms of weight gain for the potential emergence of chronic illnesses such as diabetes and hypertension.

Venter says that a healthy diet and exercise to manage weight gain related to dolutegravir sadly hardly ever leads to sustained weight loss. He adds that there are some new drugs that are effective and safe to treat weight gain but they are very expensive and are not available in the public sector.

Dolutegravir and drug-drug interactions

Dolutegravir has some drug-drug interactions that healthcare workers should be aware of, says Venter.

Otchere-Darko explains that two of these drug-drug interactions are with rifampicin (used to treat drug-sensitive tuberculosis) and metformin (used to treat diabetes). She says that rifampicin lowers the levels of dolutegravir available to the body, which means that a patient taking tuberculosis treatment should be prescribed an extra 50mg tablet of dolutegravir.

Dolutegravir increases the levels of metformin available in the body. As a result, patients who are being treated for diabetes using metformin need to have their metformin dosage decreased when being put on dolutegravir. “It [dolutegravir] helps the metformin work better, but we make sure we keep it [metformin] at 500mg and not 800mg” she says. Not doing so, she says, may result in the patient going into a diabetic coma.

A study conducted in 2020, in which 1 950 healthcare workers in South Africa were surveyed, concluded that there is a gap in the knowledge and awareness of dolutegravir’s interaction with other drugs and how to adjust the dose among healthcare workers. It also found that access to guidelines and training was positively associated with knowledge of drug interaction.

Related podcast:

Otchere-Darko tells Spotlight that to avoid these incidences from occurring, there needs to be thorough history-taking of each patient as well as “mentorship or provision of job aids that are going to remind the clinicians on a day-to-day basis on what to do when it comes to drug-drug interactions for any drug, not just TLD”.

When asked how the health department plans to tackle this issue, Mohale points out that refresher courses on revised HIV treatment guidelines coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, face-to-face training was stopped. To remedy this, he says, the department “adopted a virtual platform through the national Department of Health’s Knowledge Hub to share training and other materials”. “Unfortunately, not all clinicians are able to access the system due to data and internet connectivity issues,” he says.

He says the department’s planned interventions to improve “suboptimal knowledge in drug interaction” include an assessment of the skills deficiency by way of “the facility skills audit of antiretroviral therapy management”, after which the department will provide training.

Related article:

Mohale adds that clinicians are being directed to the knowledge learning platform for training. Spot training and mentorship are also provided during technical support visits. The department is also “continuing to distribute additional antiretroviral therapy guidelines, job aids and flip files that provide guidance to clinicians”.

Francois Venter is quoted in this article. Venter is a member of Spotlight’s editorial advisory panel. The panel provides the Spotlight editors with advice and feedback on the quality and relevance of Spotlight’s public interest health journalism. The Spotlight editors, however, remain editorially independent and solely responsible for all editorial decisions. Read more on the role and purpose of the panel here.

This article was first published in Spotlight.