Stories of sexuality, faith and migration

Learning how homophobia and transphobia operates in Africa – often through the rhetoric of a return to traditional values – reveals why many LGBTQIA+ Africans choose to leave.

Author:

28 February 2022

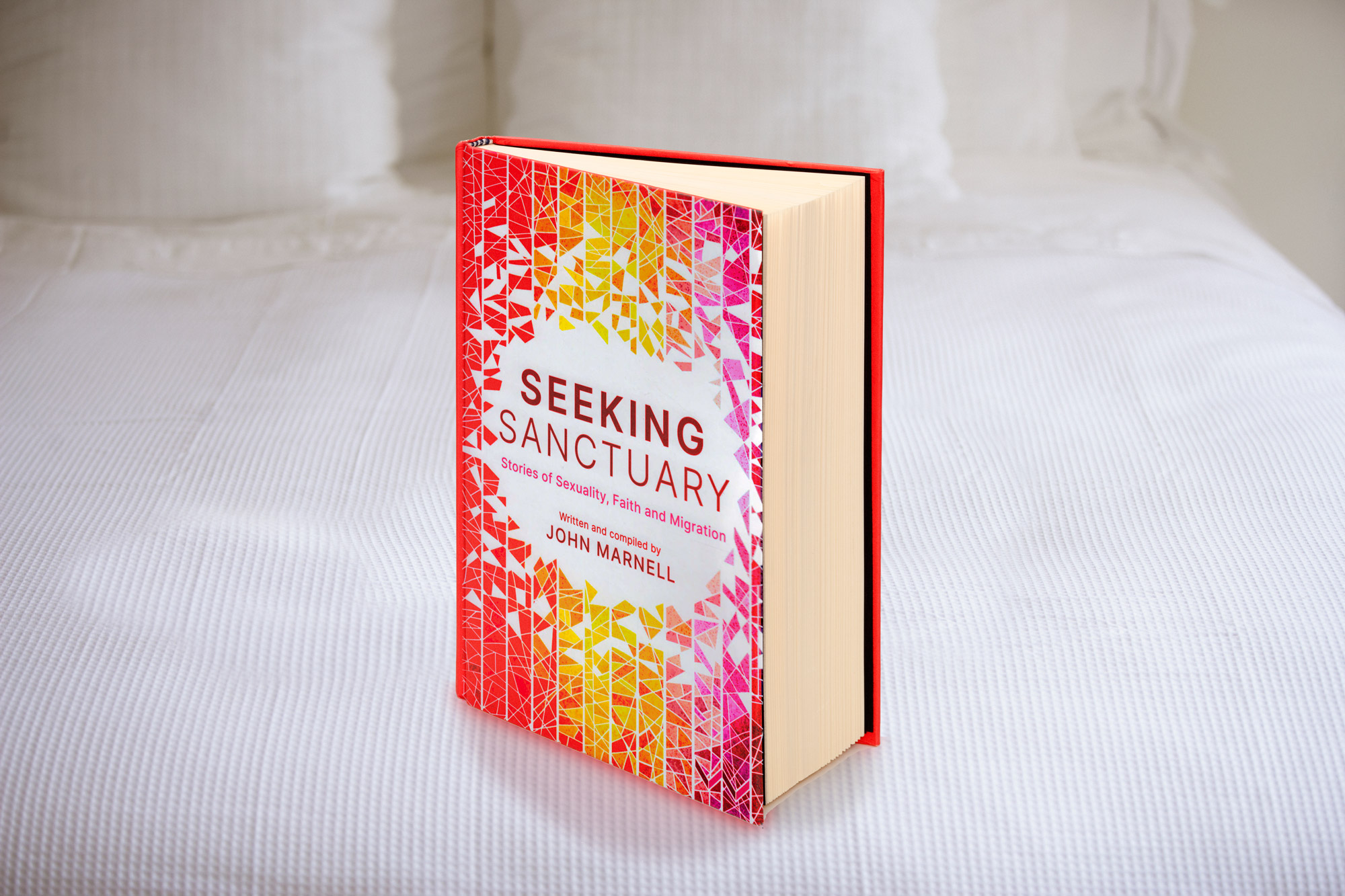

This is a lightly edited excerpt from Seeking Sanctuary: Stories of Sexuality, Faith and Migration (Wits University Press, 2021) by John Marnell.

The politicisation of faith: Religious responses to sexual and gender diversity

It is difficult to appreciate the significance of the stories collected here without knowing something of how homo/transphobia operates on the African continent. In many countries, political and religious leaders fuel anti-LGBT sentiments with moralistic rants about impending social disintegration. Underpinning this rhetoric are religious justifications for a return to “traditional” or “family” values; influential figures point to sacred texts as incontrovertible proof that heterosexuality is the only natural, normal and acceptable expression of human desire. While there isn’t space to give a comprehensive account of religion’s role in perpetuating homo/transphobia, the summary below should provide sufficient context for the narrators’ experiences.

Homo/transphobic attitudes tend to be shaped by four interlinked discourses: that LGBT people are abnormal, immoral, anti-family and unAfrican. Circulating around these discourses is a broader claim that LGBT identities or expressions are expressly prohibited under Christianity, Islam or whichever faith dominates a region. A popular refrain is that “real” African values are under imminent threat and therefore constant vigilance – usually in the form of criminalisation – is required to preserve society’s moral fabric. This is equally true for countries that have specific laws targeting LGBT people (such as Ghana, Sudan and Tanzania), countries that didn’t inherit colonial anti-sodomy laws but still see high rates of homo/transphobic persecution (such as Benin, Mali and Rwanda) and countries that have undergone formal decriminalisation (such as Angola, Lesotho and Mozambique). Even in South Africa, the country with the most extensive LGBT rights, homo/transphobia remains pervasive and is often underpinned by conservative religious beliefs.

In many contexts, the religious dimensions of homo/transphobia are plain to see. In Nigeria, for example, faith leaders of all denominations were quick to endorse former president Goodluck Jonathan’s campaign to intensify penalties for same-sex intercourse and to criminalise support for LGBT individuals and organisations. In 2010, when debates about amending the law were well under way, former anglican Archbishop Nicholas Okoh claimed that Nigeria was at risk from an “invading army of homosexuality, lesbianism and bisexual lifestyle [sic]”, echoing comments he made at an earlier press conference: “Same-sex marriage, paedophilia and all sexual perversions should be roundly condemned by all who accept the authority of scripture over human life.”

In neighbouring Cameroon, Catholic authorities regularly denounce LGBT people as unnatural, sinful and a threat to God’s model for human reproduction. A notable example is Archbishop Simon-Victor Tonyé Bakot, who in 2013 described homosexuality as a “shameful, disrespectful criticism of God”. The following year, the church released the Declaration of the Bishops of Cameroon on Abortion, Homosexuality, Incest and Sexual Abuse of Minors, in which the signatories call on “all believers and people of good will to reject homosexuality”, adding that “homosexuality is not a human right but a disposition that seriously harms humanity because it is not based on any value intrinsic to human beings”.

Related article:

Comparable statements can be drawn from across the continent (noteworthy examples come from Côte d’Ivoire, DR Congo, Kenya, Morocco, Namibia, Senegal, South Sudan, Tanzania and Zambia) and are not limited to the Christian faith. In December 2014, Malam Shaibu, an Islamic cleric from Ghana, urged residents of Accra to capture and burn suspected gay men “because Islam abhors homosexuality”. More recently, influential clerics in Mali have mobilised thousands of people in protest against the “moral depravity” of homosexuality. Mohamed Kebe, a member of Mali’s High Islamic Council and one of the organisers of a 2019 anti-LGBT rally, has repeatedly demanded violent punishments for those “who want homosexuality”.

In other contexts, homo/transphobia serves as a useful bridge between religions, offering faith leaders a rare chance to express solidarity. In 2011, a Muslim mufti joined the heads of the Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant churches in Ethiopia in denouncing plans for an HIV conference that they claimed would promote homosexuality. Further north in Egypt, LGBT rights have been condemned in similar terms by Grand Mufti Shawki Allam and Coptic Pope Tawadros II. Their framing of LGBT identities as inherently sinful in both faith traditions provides the moral justification for state repression, the most recent example being the arrest and torture of LGBT persons after a 2017 concert by the Lebanese band Mashrou’ Leila. In the wake of this clampdown, leaders from both faiths spoke out against LGBT rights, implicitly endorsing the government’s actions. Grand Imam of al-Azhar Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb said that “no Muslim society could ever consider sexual liberty or homosexuality to be a personal right”, while the Coptic Church announced that it would be organising an “anti-homosexuality” conference that would promote “recovery” from sexual deviancy.

Religious objections to LGBT rights also offer fertile ground for political point-scoring. In 2012, former Gambian president Yahya Jammeh used the swearing-in of a cabinet minister to assert his commitment to “traditional” values: “[Homosexuality] is not in the Bible or the Qur’an. It is an abomination … Human beings of the same sex cannot marry or date. We are not from evolution but we are from creation and we know the beginning of creation – that was Adam and Eve.”

Related article:

More recently, Paul Makonda, former regional commissioner for Dar es Salaam and a close ally of Tanzanian President John Magufuli, positioned his campaign to round up LGBT people as a religious crusade, noting that he would “prefer to anger those countries [that object] than to anger God”. In both of these examples, the line between secular affairs and moral regeneration was blurred, usually to the advantage of the politician involved.

South Africa hasn’t been immune to such political manoeuvres. In 2005, Jacob Zuma, then ANC deputy president, infamously described same-sex marriage as “a disgrace to the nation and to God”, a statement that firmly positioned him as a protector of culture and tradition. In the years since, local religious leaders have taken up the torch, publicly denouncing LGBT identities as sinful and abhorrent. One of the most well known is Oscar Bougardt, a Pentecostal pastor from Cape Town, who regularly conflates homosexuality with paedophilia and who has even called on ISIS to “rid South Africa of the homosexual curse”. More recently, Soweto’s Grace Bible Church has faced scrutiny after a visiting pastor described homosexuality as “sinful”, “unnatural” and “disgusting”. Details of the sermon came to light after celebrity choreographer Somizi Mhlongo expressed outrage on Twitter, sparking a national debate and frenzied crisis management from the church’s leadership.

Despite what many people assume, homo/transphobia isn’t restricted to evangelical or fundamentalist churches. Back in 2013, Cardinal Wilfrid Napier, Catholic archbishop of Durban, courted controversy when he described the legalisation of same-sex marriage as a “new kind of slavery” in which African states were being forced to “carry out someone else’s agenda”. In the wake of a public outcry, Cardinal Napier laughably asserted that he couldn’t “be accused of homophobia because [he didn’t] know any homosexuals”. While it can be tempting to dismiss these cases as straightforward bigotry, they deserve closer attention.

What do such statements tell us about the state of sexual and gender rights on the continent? Why are African religious and political leaders so quick to condemn LGBT people? How do we account for the spread and uptake of religious conservatism? There are no simple answers to these questions – the dynamics of homo/transphobia are distinct in each context – yet it is possible to observe broad trends, particularly in how anti-LGBT religious rhetoric is deployed for political gain.